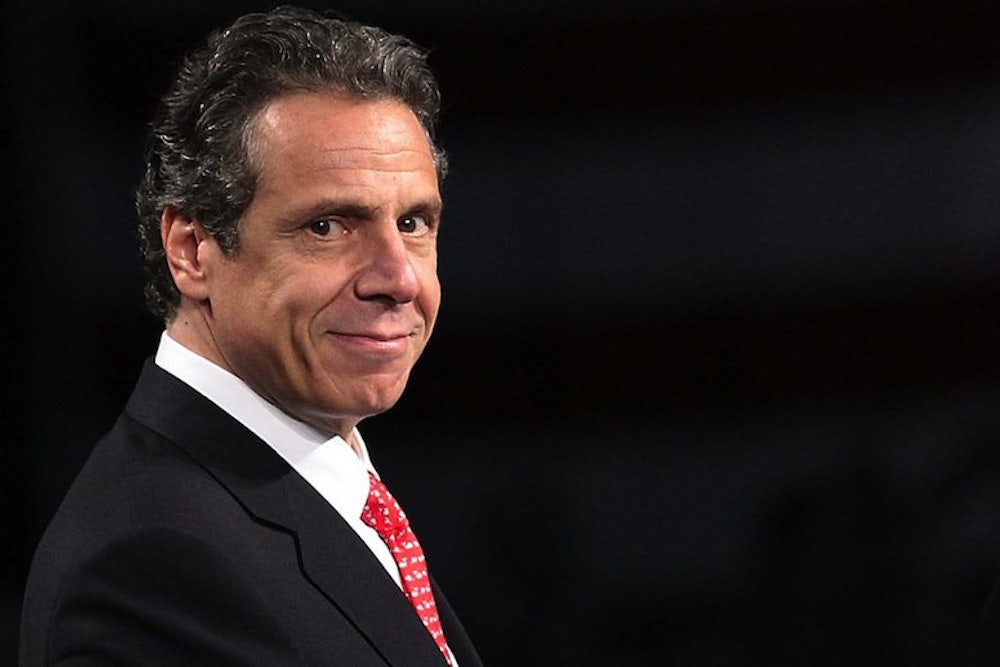

Andrew Cuomo has been leading the charge of American liberals for over two years now. The New York governor made history in the spring of 2011 by steering marriage equality through the state’s dysfunctional legislature. Last spring, he urged decriminalizing the public possession of marijuana, his response to the racially-charged pot busts under New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s “stop and frisk” regime. And just last month, he muscled through an ambitious new gun control law—the first passed anywhere in the country after Sandy Hook—that many progressives wish would be a model for how national Democrats handle the issue.

Now, Cuomo is turning to abortion rights, specifically rewriting state law to allow late-term abortions when a woman’s health is at risk or a fetus is not viable. Though many assume such a policy will go over just fine in deep-blue New York, Cuomo’s flurry of liberal activity—regarded by most observers of Empire State politics to quite plainly be the work of a 2016 Democratic presidential aspirant—is beginning to take its toll on his status as America's most popular governor. For one thing, the fight for gun control, in contrast to previous crusades, seems to have brought him down a peg. His poll numbers dipped ever so slightly from the stratosphere, an indication that a more muscular Cuomo who consistently wades into debates over polarizing social issues might prove a bit less popular than the one who made headlines early on for slugging it out with the union bosses in Albany.

More significant than any topline poll number, though, is a growing gap between how Cuomo is perceived by the urban progressives in the Democratic Party’s base and the suburban and upstate Republicans who have been instrumental in getting his agenda passed into law. Despite his apparent mastery of legislative horse-trading—one ally I spoke to called him “a modern day LBJ”—Cuomo’s transparent ambition and more unabashedly partisan approach to his job threaten to bring the current Golden Age of Empire State government to an end.

Signs of trouble began to emerge when the State Senate balked at the pot reform proposal last year. The divide between Brooklyn and Manhattan pols and moderate Republicans was too great to overcome (and a reminder that even in Cuomo’s New York, racial fears of urban youth can still drive public policy). And if the governor’s bold call to action on an array of liberal initiatives at his State of the State address in January ruffled a few feathers, his speedy push for the new gun law sent one-time conservative admirers like New York Post columnist Fred Dicker packing. Cuomo’s great haste in pursuing the law—whether because he saw a narrow window to act or, as his skeptics readily suggest, to get out ahead of potential 2016 rivals like Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley—and its reverberations around the state’s political scene raise the question of whether his growing profile as a liberal superstar may eventually come into more direct conflict with his ability to govern effectively. As Syracuse Mayor Stephanie Miner (a Democrat who made headlines of her own last week for an op-ed in The New York Times, where she slammed the governor’s latest budget proposal) told me, the expedited parliamentary procedure used to pass his gun control bill without the usual three-day waiting period “ended up throwing some mud on the accomplishment.”

Despite his robust national profile as a progressive hero, Cuomo’s tenure so far within the state has actually been defined in large part by his ability to win over generous swaths of moderate voters on both sides of the aisle outside New York City. The governor made this easy on himself by establishing a brand as a business-friendly centrist. The attendant popularity (everybody loves a technocrat!) has engendered a conspicuous lack of the “normal” gridlock most of us have come to grudgingly accept from Washington (and that New Yorkers were accustomed to from decades of practice). Suddenly, budgets got passed, thanks in large part to the governor’s great feats of Clintonesque triangulation (Cuomo allies, it should be noted, regularly compare the two men.) The political class reveled at the new state of affairs. Cuomo, after all, seemed to transform a gridlocked statehouse into a humming legislature virtually overnight, albeit one that has often left unions and other family constituencies of yore—not to mention most Democrats in the State Senate—out in the cold.

“He’s placed a strategic bet on a political profile that I call progractionary,” explains Richard Brodsky, a former member of the state assembly and fellow at the think tank Demos who serves as liberal gadfly to the governor from his perch as columnist for the Albany Times-Union. “Hard progressive on social issues like gay marriage and maybe fracking, but an austerity message on spending and taxes that fits in well with House Republicans.”

Lately, Cuomo’s persona as a lion of social liberalism has begun to drown out that of the more innocuous budget moderate. Of course, those close to him express frustration with political reporters painting the portrait of a relentlessly ambitious pol putting out targeted appeals to liberal interest groups. They argue that he’s simply carrying out the agenda he ran on in 2010, and that a change in the balance of power in Albany after a Democratic rout last fall has paved the way for progressive reform.

But in state that hasn’t been able to claim a serious presidential contender since Nelson Rockefeller in 1968—you’re not counting transplant Hillary Clinton or wipeout Rudy Giuliani, are you?—Cuomo’s aggressive agenda, regardless of whether it’s meant as a springboard into the primary snows of Iowa and New Hampshire, has begun to loom larger over debates at the Capitol. It will surely color the abortion fight, which offers a new test to the power-sharing arrangement the governor tacitly supported between Republicans and dissident Democrats in the State Senate.

“People are [increasingly] convinced he's just boosting his progressive credentials,” says one leading New York Republican who expressed admiration for the governor’s initial burst of legislative accomplishment.

The tension may come to a head over fracking. The issue threatens to bitterly divide the economically troubled upstate region (which has the shale deposits and could use the jobs) from environmentally minded New York City. But the business community, which likes Cuomo for his ambivalence about taxing the wealthy, is adamantly behind the proposal. Environmental activists, meanwhile, ran a full-page ad in the Des Moines Register recently warning that betrayal won’t be forgotten, providing ammunition for the conservative backlash that would inevitably follow a ban on fracking by Cuomo (he would almost certainly be accused of selling out the state’s economic interests to his presidential hopes). The governor has repeatedly delayed a decision, perhaps intent on getting as many bills passed as possible before setting off a firestorm one way or the other.

Miner's request in her column that Cuomo address “accounting gimmicks” is another sign that though he remains a virtual lock to win re-election next year, his identity as a hip-but-fiscally-responsible budget wunderkind is under fresh scrutiny. As Reid Pillifant points out, Cuomo wants to be able to cite a record of bipartisan happy times and broad statewide popularity as he makes the ascent to presidential politics. Bill Clinton did it with Arkansas in 1992, and George W. Bush did the same thing with Texas. Cuomo is as popular in New York right now as either of those presidents ever was in his home state, but he’s also even more ambitious (is that possible?), at least when it comes to pushing the envelope on social policy. The danger for him is that his agenda simply stretches New York’s bipartisan neoliberal Senate majority too far, and that Albany inches back toward polarization and grumbling.

Then again, if anyone had some surplus political capital to spend by wading into the hot-button ideological conflicts of our time, Cuomo is the guy. As veteran New York Democratic political consultant Hank Sheinkopf puts it, “The sky is not falling for Andrew Cuomo, though a piece of asteroid may have dropped.” Indeed, some New Yorkers were treated last week to fleeting glimpses of a celestial body, probably an asteroid or meteor, darting across the afternoon sky.

Matt Taylor is a reporter living in Brooklyn. His writing has appeared in Slate, Salon, Capital New York, The Daily Beast, and Daily Intel. You can follow him on Twitter @matthewt_ny.