As told to Chloe Schama

When I was in first grade, our family moved from Detroit to Potomac, Maryland. My father worked for a mortgage company in D.C., and every so often, we’d go into the city to have dinner or sightsee. My favorite place to visit was the Mall.

One museum had an exhibit of human skulls, each with a hole in it, sometimes two or three holes. It was explained to me that medicine men had made these holes in the people’s skulls in an attempt to cure them of migraine headaches: The holes would let the demons responsible out. That the people with the holes in their heads had gone on living was what fascinated me. Imagine having someone hammer a hole in your head, and then going in for a repeat procedure!

The Smithsonian also had a life-size replica of a blue whale mounted to a wall—probably it’s still there. I wanted to be an oceanographer back then—it was the heyday of Jacques Cousteau. My mother bought me a plastic blue whale as a souvenir and I used to play with it in the bathtub. The whale had expressive, sly-looking eyes and always seemed to want to communicate something to me. Some oceanic wisdom.

Now, whenever I go to Washington, I’m not prone to such exchanges. All I think about is power. How it is centralized there, as nowhere else on Earth, and radiates outward over the globe. I can feel it in my throat, the power, the might of empire, and I’m just going for a coffee.

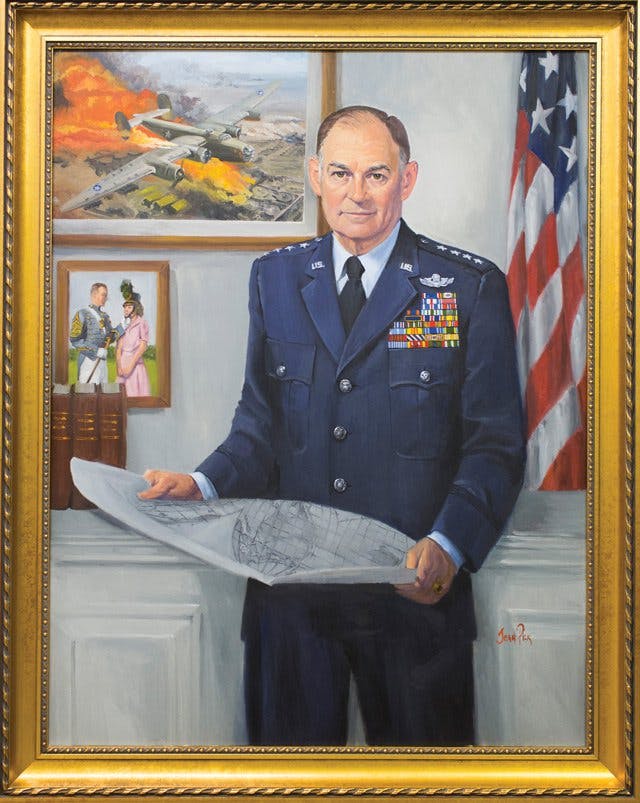

During my last trip, I was astonished to learn that a friend of mine, a former aide to Richard Holbrooke, now works not at the State Department but at the Pentagon. Since I had some spare time, he took me for a tour of the place. I saw a lot of amazing things, but what really got me were the portraits of the chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

They hang along a single wood-paneled corridor, one floor beneath the office of the secretary of defense (or SecDef, as I learned to say). As with presidential portraits, these are commissioned whenever a chairman stepsdown. Each chairman gets to have whatever he wants in the background of his portrait, whatever scene or image best represents his military career.

In terms of portraiture, the paintings are nothing special. But the backdrops contain the most outrageous imagery: airplanes exploding, decimated landscapes, sanguineous color fields. Weirdly, the backgrounds lend these ostensibly heroic portraits a sense of catastrophe. The world is always going to hell, while the chairman stands there, proudly posing, oblivious. The portraits are the exact opposite of victorious. Maybe that’s why I like them so much. They have a strange honesty. They’re also kitschy beyond belief. If they weren’t hanging in the Pentagon, but in a gallery in Williamsburg, you’d think some hipster was scoring a political point about American militarism. Most of the paintings are pretty lousy, from a technical standpoint, but for all that, it’s impossible to stop looking at them. They’re so bad they’re good.

That an image can be made for one reason but, depending on where it is and who’s viewing it, can take on a radically different meaning—that’s an idea I used to resist. It suggests that the artist isn’t in charge, that intentionality means nothing. These portraits make me reevaluate my position. What I see in them—a crazy, comedic, Monty-Pythonesque grotesquerie—isn’t what a Marine passing down the same corridor sees.