"One could never have supposed that, after passing through so many trials, after being schooled by the skepticism of our times, we had so much left in our souls to be destroyed.” Alexander Herzen wrote those words in 1848, after he witnessed the savage crackdown on the workers’ rebellion in Paris. Having been disabused by history of any illusions about the probabilities of justice, the great man was surprised to discover that he had not yet been completely disabused—that his belief in the betterment of human affairs, however mutilated by experience, was still intact; and what apprised him of his irreducible idealism was his broken heart. In 1995, I cited Herzen’s pessimistic optimism, or optimistic pessimism, in an angry article about Bosnia and the Western failure there, and glossed the lacerating sentence this way: “They did not suppose that they had so much left in their souls to be destroyed! What basis for bitterness do those words leave us, who have witnessed atrocities of which the nineteenth century only dreamed, who have watched totalitarian slaughter give way to post-totalitarian slaughter, and the racial and tribal wars of empire give way to the racial and tribal wars of empire’s aftermath? But bitterness is regularly refreshed . . . ” Forgive my quotation of myself, but I have been reading in the old Bosnian materials, in the writings of the reporters and the intellectuals who campaigned for American action to stop a genocide. I have been doing so because my Bosnian bitterness has been refreshed by Syria.

I am finding crushing parallels: a president who is satisfied to be a bystander, and ornaments his prevarications with high moral pronouncements; an extenuation of American passivity by appeals to insurmountable complexities and obscurities on the ground, and to ethnic and religious divisions too deep and too old to be modified by statecraft, and to ominous warnings of unanticipated consequences, as if consequences are ever all anticipated; an arms embargo against the people who require arms most, who are the victims of state power; the use of rape and torture and murder against civilians as open instruments of war; the universal knowledge of crimes against humanity and the failure of that knowledge to affect the policy-making will; the dailiness of the atrocity, its unimpeded progress, the long duration of our shame in doing nothing about it. The parallels are not perfect, of course. Only 70,000 people have been killed in Syria, so what’s the rush? Strategically speaking, moreover, the imperative to intervene in Syria is far more considerable than the imperative to intervene in Bosnia was. Assad is the client of Iran and the patron of Hezbollah: his destruction is an American dream. But his replacement by an Al Qaeda regime is an American nightmare, and our incomprehensible refusal to arm the Syrian rebels who oppose Al Qaeda even as they oppose Assad will have the effect of bringing the nightmare to pass. Secretary of State Kerry seems to desire a new Syrian policy, but he is busily giving our side in the conflict—if we are to have a side by the time this is over—everything but what it really needs.

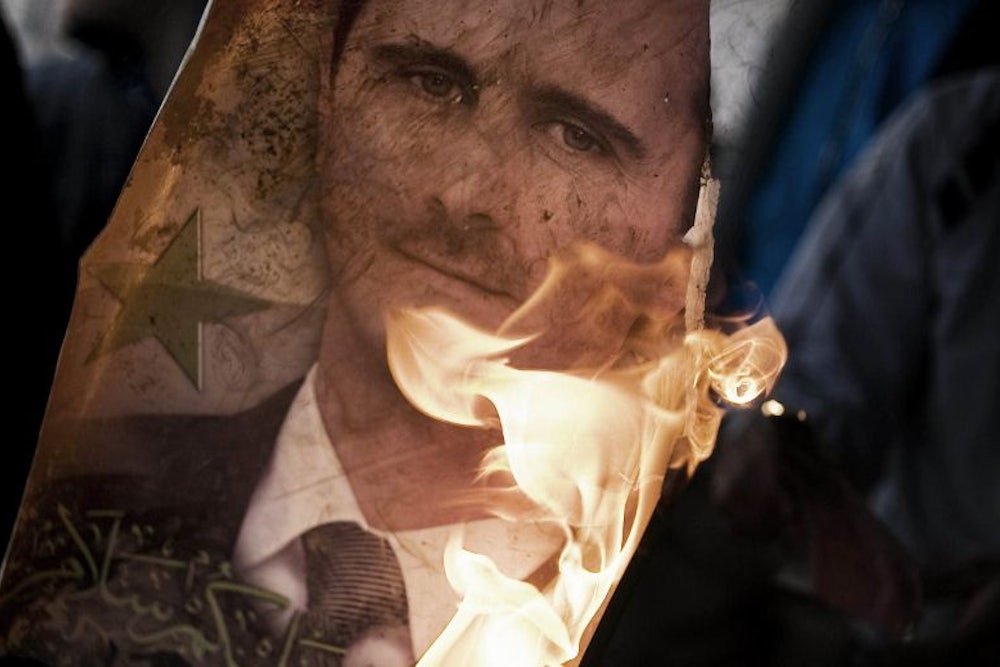

We must mark an anniversary. It has been two years since fifteen teenagers in the town of Dara’a scrawled “the people want the regime to fall” on the wall of a school, and were arrested and then tortured for their temerity. The protest that erupted in Dara’a, in the area in front of a mosque that was dubbed “Dignity Square,” was a democratic rebellion, and it swiftly spread. In Dara’a it was met by a crackdown whose brutalities were documented in an unforgettably chilling report by Human Rights Watch a few months later. Dissolve now to Aleppo in ruins, where the dictator is hurling ballistic missiles at his own population. Two years. The Obama administration may as well not have existed. Though two years into the Bosnian genocide Bill Clinton was still more than a year away from bestirring himself morally and militarily, so what’s the rush? Clinton acted after the massacre at Srebrenica. But Syria has already had its Srebrenicas, and Obama is still elaborate and unmoved. He also worries about a Russian response to American action, when Putin’s obstructionism in fact perfectly suits Obama’s preference for American inaction. People around the White House tell me that Syria is agonizing for him. So what? It is hard to admire the agony of the bystander, especially if the bystander has the capability to act against the horror. Obama likes to drape himself in Lincoln’s language, so he should ponder these words, from the Annual Message to Congress in 1862: “We—even we here—hold the power, and bear the responsibility.” Obama wants the power but not the responsibility. Unfortunately for him, the one brings the other.

Not even the advent of Barack Obama can abrogate what was learned in Bosnia in the antiquity of the twentieth century: that in the case of moral emergencies, those with the ability to act have the duty to act; that even justified action is attended by uncertainty; that military force can do good as well as evil, and that war is not the only, or the worst, evil; that the withdrawal of the United States from global leadership is an invitation to tyranny and inhumanity; that American foreign policy must be animated by principle as well by prudence, though there is nothing historically imprudent about setting oneself resolutely on the side of decency and democracy. “How do I weigh tens of thousands who’ve been killed in Syria versus the tens of thousands who are currently being killed in the Congo?” Obama recently told this magazine, as an example of how he “wrestle[s]” with the problem. Do not be fooled. It is not wrestling. It is casuistry. He has no intention of coming to the assistance of Congo, either. Obama is a strong cosmopolitan but a weak internationalist. And he is, with his inclination to disinvolvement, and his almost clinical confidence in his own sagacity, implicating us in a disgrace, even we here.