The Obama administration may remove the CIA from armed drone operations, according to recent reports—a signal that it now believes the CIA should not be involved in what its new director, John Brennan, called "paramilitary" operations. If the administration does restrict the CIA, it will also be the first major limitation on the drone program—a program Obama has greatly expanded since taking office. It does little to explain, however, how, contrary to international law, the CIA got involved in the business of killing in the first place.

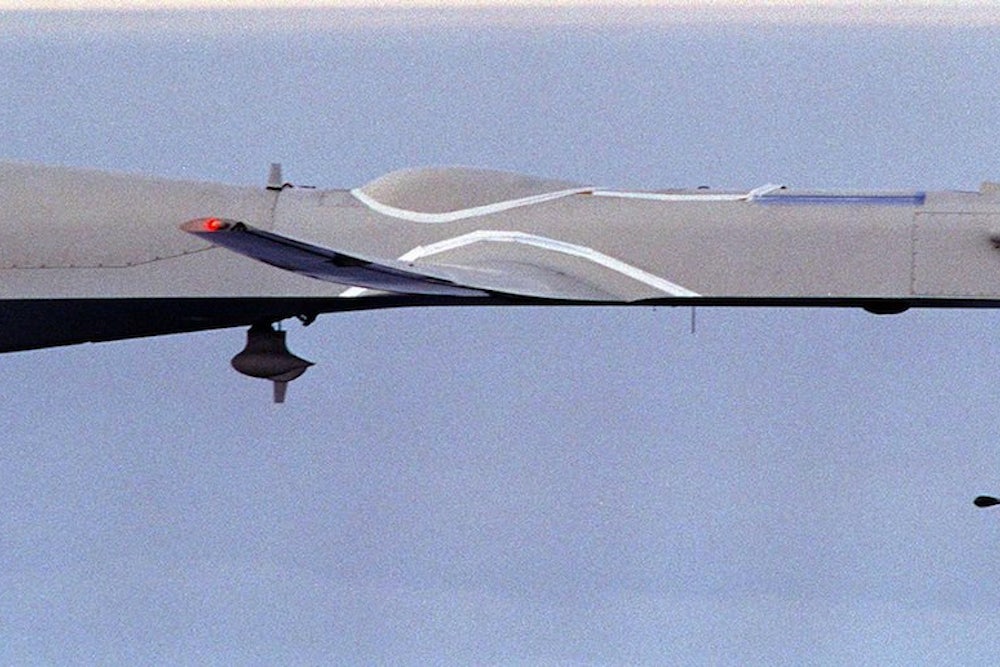

This chapter in CIA history begins in November 2002, when the agency used a drone for the first time to launch a Hellfire missile attack in Yemen, killing six men, including a 23-year-old American. Yemen was not at war with the U.S. or experiencing civil war at that time. The U.S. Air Force declined to carry out the attack because of legal concerns. The CIA had no such concerns. Thus began a long decade of killing by the CIA, with a death toll reaching 5,000 people, including 200 to 300 children.

Under the international law of armed conflict, only the members of a state's regular armed forces or associated militias meeting certain criteria may claim the "combatant's privilege" to kill in armed conflict. The combatant's privilege means those carrying out intentional killing will be not charged with a crime so long as the deaths they cause comply with the law of armed conflict. Among the important criteria that separate the CIA from lawful combatants: CIA personnel are not trained in the law of armed conflict; they are not part of a chain of command; they are not subject to a system of accountability for battlefield conduct, and they wear no uniform or insignia. Even in a place where the U.S. is engaged in armed conflict hostilities, which today is only Afghanistan (hostilities ended for the U.S. in Iraq in 2010 and Libya in 2011), the CIA is not supposed to carry out lethal operations.

The CIA might have developed differently and had the right to participate in armed conflict. It did not. The Agency was established in 1947, following the break up of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) at the end of World War II. The OSS had been part of the U.S. military, while the CIA was clearly established to be a civilian intelligence agency.

Nevertheless, the CIA has engaged in lethal operations in and out of armed conflict for decades. Its activities were particularly infamous during the Vietnam War and with regard to a number of assassinations. Following the Church Committee hearings into the CIA, Congress placed the Agency under greater scrutiny. In 1975, President Ford signed an executive order prohibiting CIA assassinations. President Reagan confirmed and extended the assassination ban in 1981.

Then 9/11 happened. The CIA began to carry out secret detention, waterboarding of detainees, and military strikes on people far from any battlefield. Bush administration lawyers produced secret memos asserting rights to detain people without trial and to conduct harsh interrogation. The memos released to the public do not discuss the right to kill people with military force beyond battlefields or the right of the CIA to do any of these things: detain, torture, or kill. President Obama ended CIA secret detention and harsh interrogation. He did not end CIA involvement in armed drone attacks. The new administration, like its predecessor, tried to keep CIA activity secret, but President Obama has authorized so many CIA drone strikes the practice could no longer be denied without derision.

When this fact became obvious, administration lawyers, starting with State Department Legal Adviser Harold Koh in March 2010, began attempting to argue that intentional killing beyond battlefields is lawful. The term "global war on terror" was replaced with a synonymous phrase: "armed conflict with al-Qaeda, as well as the Taliban and associated forces." To answer critics of this flimsy construct, other arguments have been layered on, including national self-defense under United Nations Charter Article 51 and consent. Sometime after Koh's speech, the Department of Justice prepared lengthy memos attempting to justify the targeted killing of American nationals suspected of terrorism. A sixteen-page summary of the documents was leaked to the press in February 2013, just before John Brennan's confirmation hearings to head the CIA. It again discusses worldwide war and self-defense, but not who may lawfully deploy military force.

Neither the assertion of a worldwide war, Article 51 self-defense, or the type of consent at issue can justify the vast majority of U.S. drone attacks beyond battlefields. The claims are simply repeated with no attempt, to date, to respond to direct challenges. Even the CIA's General Counsel, Stephen Preston, in an April 2012 speech at Harvard Law School, titled "The CIA and the Rule of Law," simply repeated the inadequate arguments that the United States may use drone attacks. He did not explain how CIA personnel qualify for the combatant's privilege to use military force on behalf of the U.S.

Meanwhile, scholars have explained the prohibition on CIA use of military force since the 2002 Yemen attack; Gary Solis, a former Marine Corps lawyer and now Georgetown law professor, published a critical op-ed on CIA killing in a 2010 Washington Post op-ed: "[T]hose CIA agents are, unlike their military counterparts but like the fighters they target, unlawful combatants."

Defenders of CIA drone operations typically point to the president's right to withdraw Reagan's Executive Order against assassination or the right of the president as commander in chief to order the CIA into action. No response has been made to the point that the CIA is barred from using military force. Harold Koh, Stephen Preston, Eric Holder, and John Brennan have all acknowledged in their many speeches that international law binds the U.S. when it comes to using armed drones. They have all overlooked that international law bars CIA killing.

Interestingly, international law does not prohibit espionage per se, as it does intentional killing by those lacking the combatant's privilege. Land, sea, and air boundaries must be respected, but spy satellites are tolerated. (The Chinese seem to view computer hacking as the legal equivalent of satellite intelligence.) The law most relevant to spying is local law. Recall the affair of CIA contractor Raymond Davis in Pakistan when Obama officials tried to claim Davis was an accredited diplomat to provide him with immunity from Pakistani law. CIA agents who kidnapped a cleric in Milan have now been tried and sentenced in absentia for violating Italian law.