Today marks 44 years since the beginning of the brutal, deranged murder spree instrumented by Charles Manson and his followers. Here, we bring you The New Republic's original review of Helter Skelter, by Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry.

Helter Skelter is an indifferently written social document of rare importance. It tells how the mass murderer Charles Manson and his followers were trapped, tried and sentenced, in fact, everything medicine and law will probably ever know about their crimes and lives. The authors are superb when dealing with fact and sound, when unraveling motive. They even make an honest try at getting to the final why of Manson, though they fail, and freely confess it. Bugliosi, prosecutor of the Tate-LaBianca murders, writes:

[Many] factors contributed to Manson's control over others … [but] I tend to think that there is something more … Whatever it is. I believe Manson has full knowledge of the formula he used. And it worries me that we do not.

It worries me too. Charles Manson was probably the weirdest mass murderer in the history of the United States. It would be nice to think him a social aberration so bizarre as to be the product of nothing but chemical confusion, never to be repeated again. But too much in his story seems rooted in a culture he twisted to his own uses. It is hard to escape the conclusion that the counterculture of the 1960s—which offered us beautiful music, new ways to live our lives, and the will to end the war—gave birth as well to Charlie Manson.

That understanding is explicit in the work of Bugliosi only to the extent that he had the wisdom to seek motives far outside the usual range of police thinking. So the names of the Beatles and the Beach Boys, of prominent film-and fashion makers of the time, crop up again and again in his documentation. "lf I'm looking for a motive, I'd look for something which doesn't fit your habitual standard … something much more far out," Roman Polanski advised one detective. The detective didn't take that advice—beyond briefly making Polanski himself a suspect—but the prosecutor did. He even went to the length of reading newspaper astrology columns dated around the time of the murders to see whether Manson might be getting his tips from the stars. A small thing, and indeed a wrong direction. It meant that the law was beginning to think like its quarry.

But Bugliosi's imagination was still too far removed from the Manichean split in Manson's world to make the connections that would prove evident to other observers.

The summer of the killings was the summer of 1969. One of its central events, the Woodstock music festival, capped the happiest explorations of the counterculture and another, the moon shot, summed up the best powers of the technology that opposed it. It was hell summer. If some of us had gone to the moon and others to Woodstock to OD on music in the mud, still others persisted a world away with cluster bombs and napalm. A political dynasty went off a bridge at Chappaquiddick, not much minded in the general wake for a politics that had died in Chicago the summer before. Black people had burned their own cities that year—would they do ours this complicated season? Soon a black man would die at a rock concert as Mick Jagger sang "Sympathy for the Devil," pausing at the time of the murder—though still unaware of it—to demand "Why is there always trouble when we sing this song?" And later actions, half-understood, would flare away from the central events of the summer of '69: two princes and a queen of rock-and-roll to die within a year of each other; students to be shot down by the national guard within the walls of their state universities; another to be blown to bits by his radical brothers, and then some of those brothers and sisters to blow themselves to bits, bomb-building in a basement while in Asia the bombing war went on.

Who will swear there is no smallest causal nexus between these events and the darkest flower of those August days when a band of killer androids, hand-tuned by Charles Milles Manson, crept into two houses and slaughtered on all sides in the name of the Beatles, the Bible and the little godling who called himself Man's Son?

No: the finest taste for nostalgia will not redeem some days of the summer of '69.

It was a time that found many of the best minds among us steeped in notions of black magic. Even as two years before, radical pragmatism had been sauced in Yippie liturgy in hopes of razing the Pentagon with a grim and joyful song, now Norman Mailer, a mover of that noble march, would reflect on mindless murder without surprise as the work of a young man "steeped by report in no modest depths of witchcraft." And Marshall Berman, seeking to relate the experience of the '60s to the legend of Faust (in a fine essay to be found in New American Review #19) remembered that Pentagon march in diabolical terms, reflecting on the psychic links between the devil and his desert prophet, Charles Manson. "Remember," one of his professors chided him when he was on his way to Washington, "Faust gets hold of those powers because he's really serious about the devil. Are you?" Soon we all would have to be.

A sense of the demonic is missing from this book; Ed Saunders' The Family may be consulted to supply it. But everything else is in these pages: the interminable police work (much of it poor) and elaborate theory-building, the careful legal mechanics rewarded by the dramatic trials, the links of rock-and-roll to revolution (and Revelations), an endless collection of telling small details.

The police work can be dismissed with the observation that it's a miracle the Mansonoids were ever brought to trial. According to Bugliosi the detectives working on the Tate murders were old-style, up-from-the-ranks types who wouldn't give the sleek, schooled LaBianca operatives the time of day, so it was some little while before the cases, despite their similarities, were connected.

For some time officers took no interest in the fact that a variation on the word "pig" was scrawled at the scene of the different murders. Deputy coroners often failed to do blood subtypes or measure wound dimensions. A form letter trying to trace the murder gun went to every police department in the country—except the most concerned substation of the L.A.P.D. (The weapon was finally found by chance by a child, then lost for a time in the evidence files.) A TV news crew located some incriminating clothing that police hadn't bothered to look for. And these screw-ups hardly exhaust the list.

Bugliosi cites a number of lucky breaks and is not bashful about his own high competence. No doubt others involved in the case will take angry issue with many of his assertions. But this concerns us less than the horrors uncovered once Manson and the family were successfully brought to trial.

The prosecutor was confident he could get convictions of the actual killers on evidence alone, but to convict Manson, he had to prove overwhelmingly Manson's utter domination over the family, which suggested in tum that he would have to establish motive. It would be a large job, and would take him into areas where the law need not usually go (there is no legal requirement for a prosecutor to prove motive; he need only demonstrate an act has been committed).

To accomplish this he presented the jury with examples of Manson's incredible power over his people, documenting again and again techniques of exploitation by sex, by drugs, by isolation, by fear and even by music (the counterculture's greatest gift, and his bond to kids many years his junior), but most of all by the repeated elaboration of his philosophy to an eager audience whose values it endorsed and whose sense of alienation and rejection it applauded.

Manson had a theory of opposites, involving a "love" that called for killing (Susan Atkins would say she had to love Sharon Tate a lot to kill her with the relish she felt) and for desecration of the dead (the Tate killers had hoped to pluck the eyeballs from their victims but regretted they hadn't the time). A drive to realize one's self, so long as that self remained enslaved to Manson. A tacit understanding that Manson was Jesus Christ. A hope to be part of the saved on that great day when Charlie would trigger helter-skelter and the survivors returned to rule the world…

Helter-skelter lies at the core of Manson's thinking. At his trial he defined it as "confusion, literally," and suggested it was "only what lives inside each and every one of you." Susan Atkins gave a fuller account of the thinking of her lord and master. "…Helter skelter was to be the last war on the face of the earth. It would be all the wars that have ever been fought, built one on top of the other… You can't conceive of what it would have been like to see every man judge himself and then take it out on every other man all over the face of the earth." Helter-skelter was Charles Manson's design for Armageddon: by committing crimes like the Tate-LaBianca murders and leaving clues to throw the blame on black power groups, Manson hoped to force a police crackdown on the blacks who would retaliate with war against the whites. The blacks would win. Then Manson and his band would emerge from their magical cave under Death Valley and "lead" (i.e., reenslave) the victors.

It is harder now than it would have been in the '60s to imagine children dumb or drugged enough to be entranced by such a story. But Manson had an old con's skill (he had spent most of his life in prison—had even begged to be kept inside before being released for his final killing spree) at picking the members of his band: the girls were young, homeless, fanciful, at war with their parents—the boys were kept in line by being given the girls. In the moonlit desert, in the ready-made romance of the decaying Spahn Movie Ranch, they would sit adoringly around Charlie and hear him make promises of a future that would give them the power they'd never had, heal wounds that burned fresh daily. There were drugs, sex in constant splashes every which way, and all the other sticks and carrots that kept the kids in line. But there was something else in Manson that could turn them from borderline psychotics into psychopathic killers of unparalleled cruelty. Bugliosi admits it, but he cannot quite say what it is.

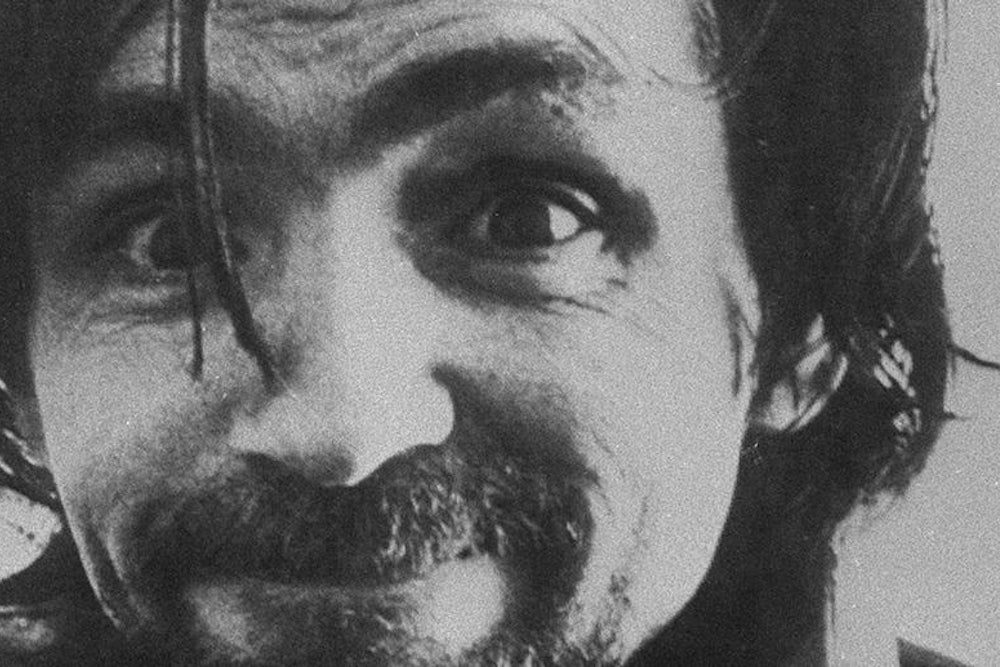

Most likely no one will ever be able to. Unlike Bugliosi I doubt Manson himself is in possession of his "formula." The element of the demonic, introduced here to supply the book's only missing note, is not something any pragmatic intelligence feels comfortable with, but one glance at the famous Life cover photo of Manson is almost enough to make disbelievers switch sides. (It's included in the exhaustive photo section of this book.) I don't think there's any possible doubt that Manson was a demon—not possessed by one, was one. His hellish history makes any appeal to a supernatural principle superfluous; but having both motive and motive force behind it, we are still shy of understanding. To come closer to that we must close in on the ideational undertow of helter-skelter, the art where Manson's twisted art originates.

It is in music. Manson was convinced that the Beatles were sending him coded messages in support of helter-skelter, particularly in the double "white album" released in 1968; he took the term from one of its songs. As family members testified at the trial, he had worked out with scholarly precision correlations between his murderous doctrine and virtually every line of every lyric; more than that he had searched beyond his origins in the Beatles to their origins in the Book of Revelations, where in the ninth chapter he found the "four angels" with "faces as the faces of men" but "hair as the hair of women"; even mention of their electric guitars ("breastplates of fire") and much else besides. There was word of a fifth angel, and the family knew who that had to be. One translation of Revelations calls him Exterminans.

Revelations 9. Is it chance that the Beatles song Manson liked best is called "Revolution 9"? Or that the Bible chapter ends, "Neither repented they of their murders, nor of their sorceries..."? And the song ends on the grunting of pigs, and machine-gun fire?

These connections bring us nearer Manson's place on the edges of the counterculture, but they entail risks. A man dies while listening to a hymn to Satan and its author must wonder thereafter if his verse unsheathed the knife; others are sent forth to murder in service of a sick vision founded in the saving vision of four poets. Is an artist responsible for murders committed in his name? A subculture responsible for murderous philosophies conceived under its influence? The Manson murders invite the question.

There are other roots, of course. Comparisons between Manson and Hitler are by no means fatuous; this book offers many, in detail. It's even possible to relate the family to the SS, in that both were unified by blood lust and blood guilt. In more usual terms of social psychology, Manson's history of repeated childhood neglect, abandonment, institutionalization, petty crime and reimprisonment add up to a young man who's likely to have some trouble with daily life.

Manson may deny a "strange power," but he embodied and engineered a very strange scene. The notion that Manson reflected the dark secret side of the effort of some of us to reorganize our private and political lives in light of a new vision derived in unequal measure from rock, dope and the renunciation of secular society—comes closer than any other to explaining him. It was Manson's art to seize on what was totalitarian in the counterculture (notably its doctrinaire certainty that the only true wisdom is the received wisdom of a guru) and polish it into a deadly gift for his elected. So, to an extent, one of the most hopeful movements in American life in this century created one of our darkest social chapters.

The Weatherpeople, Berman notes, "…cheered and celebrated the Satanic horrors of the Manson murders as an exemplary political act. The victims were simply 'pigs,' and having been thus written off, they could be righteously rubbed out: their murder was a triumph of the revolutionary will." Helter Skelter cites additional ugly evidence: a huge volume of love letters to Manson in prison from young girls wanting to join the family; an underground newspaper that proclaimed him "Man of the Year"; a proliferation of FREE MANSON buttons.

Now five years are gone, the counterculture with them. Manson is jailed, and he won't be out for four years or forever. The family is jailed or scattered. It does not seem to have left heirs, though it has most certainly left a heritage. Our subsequent mass murders have been old-style, ugly enough, but without the wide significant ripples of the Tate-LaBianca case. So this book may have arrived too late to interest the audience it deserves. But its great length and flat language notwithstanding, it should be read. Manson's words after his conviction give reason enough why we all should know all of his story:

“Mr. and Mrs. America—you are wrong. I am not the King of the Jews nor am I a hippie cult leader, I am what you have made of me and the mad dog devil killer fiend leper is a reflection of your society. … Whatever the outcome of this madness that you call a fair trial or Christian justice, you can know this: In my mind's eye my thoughts light fires in your cities.”

Burning still.