You could make a good case that the last ten years have been relatively good for liberals. Democrats won two out of three presidential elections and controlled Congress for four years, two of them overlapping with the Obama presidency. It was a too-brief window, but during that time they managed to accomplish an awful lot—passing major of the financial sector, ending the war in Iraq, launching a major regulatory effort to tame climate change, formally allowing gays into the military, and finally passing something that looks like universal health care.

There have been setbacks and disappointments too. Democrats never restored tax levels to what they were during the Clinton era, recent fiscal deals have choked some vital domestic programs, and the economic recovery has been fitful. Meanwhile, a generation of conservative judges have handed more power to states, which in some parts of the country has given the right new license on abortion rights and other issues. But thanks to favorable demographic changes, Democrats seem in strong position to protect what they’ve accomplished nationally and maybe, sometime soon, move on to new projects—whether it’s redoubling efforts on climate change, doing something about work-family issues, various political reforms, or aggressively attacking inequality.

Liberals are in this position for a whole bunch of reasons. One of them is an organization that, on Thursday, will celebrate its tenth anniversary. I’m talking about the Center for American Progress, and its affiliated political arm, the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Like most people who work in or around politics and identify with the center-left, I’m hardly a disinterested observer. I am broadly sympathetic to the organization’s political outlook, know many people there personally, and have participated in their events. But I think most people in Washington would agree that CAP plays a vital role in the liberal ecosystem—doing a job that, ten years ago, nobody else was doing.

The right has long had a set of institutions that serve a similar role. The best known of these is the Heritage Foundation, which after its establishment in 1973 helped craft the conservative policy revolution that started with the election Ronald Reagan and crested, finally, during the presidency of George W. Bush. Heritage served multiple roles during that span—as an incubator of ideas, a supplier of arguments, and a source of talent. The brains and money behind Heritage saw the think-tank as an antidote to the prevailing liberal consensus in Washington, as put forth by places like the Brookings Institution (and academia generally) and reinforced by the New York Times (and rest of the media establishment). But there was a certain irony in this mandate: Whatever the ideological sympathies of these supposedly liberal institutions, or the people within them, they were not avowedly political organizations. On the contrary, they strove to maintain—and, I would argue, succeeded in maintaining—a strict posture of non-partisanship and even non-ideology. Other think-tanks and organizations had more clearly progressive outlooks, but even they tended to be heavily analytical and/or narrowly focused. They did invaluable work. (The Economic Policy Institute's annual State of Working America may be the single most important non-government report on inequality.) But one niche remained unfilled.

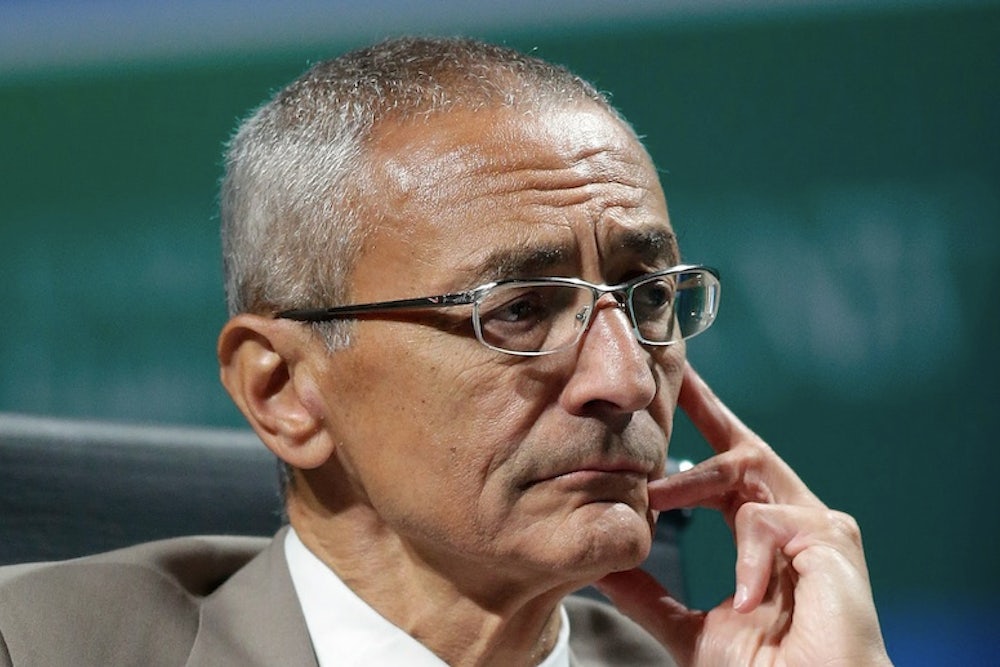

On the left, the only true analogue to a group like Heritage—a group with a broad issue portfolio, determined to blend policy and politics—was the Democratic Leadership Council and its affiliated think-tank, the Progressive Policy Institute. It had considerable influence on the Democratic Party, particularly during the 1990s, when Bill Clinton—an early DLC member—became president. But DLC/PPI was all about pulling Democrats, and public policy in general, to the right. By the late 1990s, liberals were anxious to pull the party and the conversation back to the left. That was the idea behind CAP, as it founder, longtime Clinton adviser John Podesta, explained at the time. “One of the things that The Heritage Foundation, I think, has done a good job of is that they've gotten their people out into that public debate,” Podesta told National Public Radio in 2003. “They've had a strategy to not just come up with analysis, not just to write good ideas in papers and in academic journals but to actually get out and fight for the hearts and minds of the American people for public opinion. And that's what we aim to do.”

Neera Tanden, a veteran of both the Clinton and Obama administration, succeeded Podesta in 2010. She had helped him establish the institution and remembers the mission the same way he does:

We thought that the right benefited from conservative think tanks that defended both conservative principles—limited government—and the policies that those principles led to—cutting everything. So we wanted to create a multidisciplinary think tank that would argue for progressive principles—fairness, opportunity, and so on—and for the policies behind them. Also, a multidisciplinary think tank can do the work between issues. So energy issues are a mix of the environment and economics; if you are just an environmental organization, you may lose that economic perspective. And some of our best work is in the areas that bring disciplines together. That is an advantage the right had over us.

Has it worked? Allowing for my bias, again, I think the answer is yes. The contours of Obamacare, the plans for Iraqi withdrawal, green jobs in the Recovery Act—CAP had a hand in developing all of these ideas. In so doing, it frequently borrowed heavily and adapted the work of others, including other liberal think tanks in Washington. But precisely because CAP was pulling together the politics and policy, it was in a position to promote those plans with officials and lawmakers—quite a few of whom, conveniently, were former CAP affiliates. (Among those who served or continue to serve in the Obama Administration are Melody Barnes, Brian Deese, Rob Gordon, James Kvaal, Jeanne Lambrew, Tara McGuinness, Jennifer Palmieri, and Denis McDonough.)

“The Center for the American Progress has been and continues to be indispensable to the Democratic Party and to the country,” says Senator Charles Schumer, who knows a thing or two about blending policy and politics. “Their creativity, political savvy, and dedication to good public policy can’t be overstated.” Adds Jim Manley, longtime advisor to Senators Ted Kennedy and then Harry Reid:

Thank god for John Podesta, then Senator Clinton and everyone else that had the vision to see that progressive Democrats needed an alternative to the intellectual arguments that outfits like Heritage and AEI were providing to the republicans on a regular basis. Like Heritage and AEI, Democrats use the Center for a wide range of issues, kind of like a one stop shopping for policy arguments, knowing that their work is solid and their research can stand up to scrutiny.

An ever-present danger of an organization like CAP and its affiliated Action Fund is that it becomes too close to the Democratic Party—losing its independent voice and becoming an reservoir of stale, familiar ideas rather than a conduit for new ones. I’m not on the inside, so I have no idea whether the organization has pulled punches for the sake of preserving influence or satisfying a donor. But most well-connected groups in Washington do, at least once in a while. The more issues on which an institution tries to have political leverage, the more it must set clear priorities—playing up some issues and playing down others.

But it’s not like the organization never takes shots at friends. In 2011, for example, CAP blasted an EPA rule on ozone that environmentalists saw as a gift to the oil industry. It also seems to take intellectual honesty seriously. That's one reason I frequently quote Michael Linden, who does economic analysis, and Igor Volsky, who writes on health care for the Action Fund's "Think Progress." (The other is that they're really smart.) There was a time when I could say the same thing about Heritage, or at least some of the people who worked there. That's a lot harder these days, now that Heritage is under the leadership of former Senator Jim DeMint and increasingly reflects his way of thinking. (It's not shy about challenging the Republican Party, but the arguments it deploys don't hold up well to scrutiny.) The space that CAP now fills on the left, for a strategic but honest effort at policy advocacy, is thinly populated on the right. Maybe someday that will change, because conservatives will look at what Podesta and his colleagues created ten years ago—and decide they, too, could use one of those.