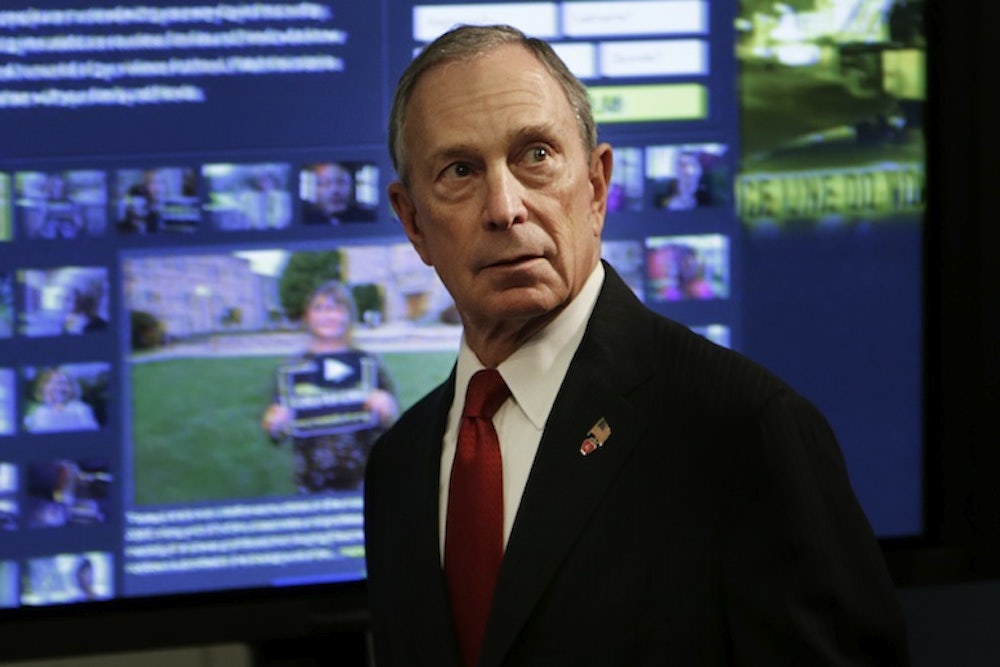

On a leafy stretch of East 78th Street, behind a locked, unmarked door with wrought-iron detailing, the office that housed Bloomberg View for the past two and a half years feels more like some oaky, patrician club than a corporate outpost. In the high-ceilinged lobby of the Stanford White–designed townhouse, a filigreed mirror hangs over a plush orange couch, and an imposing central staircase rises to unseen upper floors. Through an open doorway to the right is an intimate dining room, with high windows and silver warming trays against a back wall. On a given morning around 7 a.m., Michael Bloomberg himself might be found sitting there, sipping his coffee and reading the news.

Since the opinion arm of Bloomberg News launched in 2011, its cushy digs have spurred envy among many occupants of the glassed-in space station that is Bloomberg H.Q. But several days ago, View moved out of the townhouse it shared with Bloomberg’s foundation and into the mothership on Lexington Avenue, where the mayor will land after leaving office in January. And as his term winds down, it’s rumored that Bloomberg will be taking a more active role in the site than ever before.

This tiny corner of his empire—with its 28 full-time staffers—has been, in some ways, an especially personal media endeavor for Bloomberg. Conceived as a corrective to the partisan opinion racket that the mayor disdains, it publishes editorials in the data-heavy, prescriptive style he favors: e.g., “HOW TO KNOW WHEN WE'VE ENDED THE $83 BILLION BANK SUBSIDY." It also features bold-faced contributors—including Jeffrey Goldberg, Margaret Carlson, Peter Orszag, and Ezra Klein—who pen regular op-eds. On the whole, View is central to Bloomberg’s self-image as a global media mogul and thought leader. “I think Bloomberg View is one of the ways in which he feels he is bypassing the need to buy the Times,” says a columnist.

But nearly three years into its existence, despite its lofty mission and its gallery of bigwigs, View has largely failed to spark debate among the cultural elite or usurp the clout of The New York Times’ op-ed page. What Bloomberg View has become, however, is a reflection of just how incompatible its founder’s ideas about influence are with the rest of the world’s.

From the beginning, Bloomberg devised his opinion website as if it were the Davos of dinner parties. He approached a handful of prominent journalists he deemed like-minded intellectuals and made them offers too eye-popping to refuse. For on-site staffers there were ritzy amenities, such as the townhouse’s wireless-equipped rooftop Japanese garden. One former columnist based out of town had travel and accommodations written into his contract, which ended up including stays at five-star Manhattan hotels. Another was told off the bat that he’d be making “six figures, the first of which will be a two” with no specifications for weekly output. And for particularly big-name contributors, the numbers are even more boggling. Michael Lewis makes around $8,000 per 1,200-word column.

Bloomberg also hired two executive editors for close to half a million dollars each: David Shipley, the widely respected op-ed page editor at the Times, and Jamie Rubin, a former assistant secretary of state under President Clinton. Their styles could hardly have been more different. Rubin, married to Christiane Amanpour, is a big personality and a smooth talker. Shipley is mild-mannered and discreet. After ten months, Rubin was fired, which came as no surprise to him. “I had wanted to be part of something new, more like a centrist think tank than yet another opinion website with a limited readership,” Rubin said.

For columnists, however, the limited readership was offset by the sense that they were being read in the highest corridors of power. One former columnist walked into the townhouse dining hall one morning to find the mayor on his cell phone, reading aloud from a Bloomberg View editorial about Greg Smith, the former Goldman Sachs executive who resigned via Times op-ed. Asked who was on the other end of the call, the mayor replied: “Lloyd Blankfein.”

Writers were also wined and dined by Bloomberg himself. At a dinner for columnists at the Palm, the mayor promised not to censor anyone, assuring them that they could, within limits—one of which was advocating against a woman’s right to choose—write whatever they wanted. At another salon-style dinner in a private hotel dining room, Bloomberg explained that he didn’t care that the site was losing money. His priority was providing a value-add to Terminal subscribers: that is, the tony network of financiers who pay upwards of $20,000 a year for access to the software system that is Bloomberg L.P.’s cash cow. One former staffer explained: “He wants the [international] glitterati, his peer group, to start talking about what’s in Bloomberg View.”

But the result of gathering all these heavyweights under one virtual roof has not exactly lit a fuse under the intellectual world. Instead, the output of Bloomberg View has been mostly flat—a particularly bloodless kind of centrism, churned out, in some cases, by journalists whose primary loyalties are to other outlets. The demand to be empirical, to pry apart every facet of domestic and foreign policy with blunt Bloombergian logic, has led to a slew of milquetoast editorials. Recent headlines include “HONORING NELSON MANDELA'S LEGACY” and “OBAMA MUST NOW MOBILIZE THE WORLD.” And allowing talent to write as the spirit moves them has resulted in some head-scratchingly miscellaneous op-eds, such as Orszag decrying the fake-tanning industry. It’s no wonder that the columns have struggled to survive on the Web, even as two View writers were nominated for a Pulitzer last year for their analysis of the European debt crisis. The site, which currently gets around 2.8 million uniques a month, is practically dull by mandate. “Editors go over there and it’s like Night of the Living Dead,” said one columnist who left the company. “They are just mummified and never heard from again.”

The columnist explained, “Bloomberg View was never able to be part of the Internet, because it was caught between the real Internet and this parallel Bloomberg proprietary Internet”—the rarefied world of Terminal users. In a stroke of irony for a place that has sunk so much cash into hiring big names, a 2012 company-wide McKinsey study found that one reason for Bloomberg View’s low readership was that the majority of people had never heard of most of its columnists. The study, though, has yet to stir up much real change.

Today, Shipley is the site’s sole executive editor and breakfasts with Bloomberg regularly. Shipley is popular with employees—“He’s a great editor and a mensch,” columnist Jonathan Mahler said—but some describe him as the consummate company man. According to one columnist, “He’s like Mr. Rogers in that it’s always a beautiful day in the neighborhood. ... He’s a very Pollyannaish kinda guy”—and that is ideal for the mayor, who “is not gonna take any crap. ... He wants somebody that listens to him.” The columnist even compared Bloomberg L.P. to a “petro-state,” in which the Terminal is oil: “It’s always producing money, but you don’t have to manage well because it’s all excess.”

But Shipley clearly wants View to be more than just another skyscraper in Bloomberg’s Abu Dhabi. The editors are planning a redesign, tentatively scheduled for January. And in April, the site brought on a publisher, Huffington Post executive editor Tim O’Brien, to spearhead efforts to engage a broader audience. While traffic may not be a metric of influence for Bloomberg, Shipley feels differently. In June, he hired the popular blogger Megan McArdle even though, in the wake of the Newtown massacre, she had written a controversial op-ed about the impracticality of gun control. According to one columnist, View editors just hoped Bloomberg hadn’t read it.

Bloomberg’s hazy but constant presence has caused some confusion. Although he has largely kept his promise not to meddle, he has been a fixture at the townhouse, often stopping by to chat with or even lecture at the big thinkers he has spent millions to collect. One columnist recalls sitting down with a bagel in the dining room and getting waylaid by the mayor with a spiel about stop-and-frisk. For editors, divining his thoughts on subjects aside from, say, gun control or public health has proved tricky. Once, a staffer recalled, they ran an editorial on Syria, only to be firmly informed, to everyone’s surprise, that Bloomberg disagreed. After an editorial about derivatives was published, he also let his displeasure be known. “If I were running Bloomberg View,” says one well-known editor of another media outlet, “the thing I would most want would be for Bloomberg to get hit by a bus.”

But Shipley, needless to say, insists otherwise. On a recent fall afternoon, he sat in one of Bloomberg H.Q.’s fishbowl conference rooms, wearing a tie flecked with dainty polka dots and a crisp blue shirt. The mayor already has his future desk picked out, next to global media CEO Justin Smith, but there has been no definitive word on what exactly he will be doing at the company. “While I have literally no idea what is going to happen after [the mayor’s term], I would welcome his involvement,” Shipley said, as Bloomberg L.P.’s chief of communications nodded from across the table. Shipley clasped his hands on his lap and glanced out at the bustling newsroom where View would soon reside. Then he smiled. “We are about to hire a new Web producer,” he said. “If the mayor wants the job, he’d be fantastic at it."

Laura Bennett is a staff writer at The New Republic.