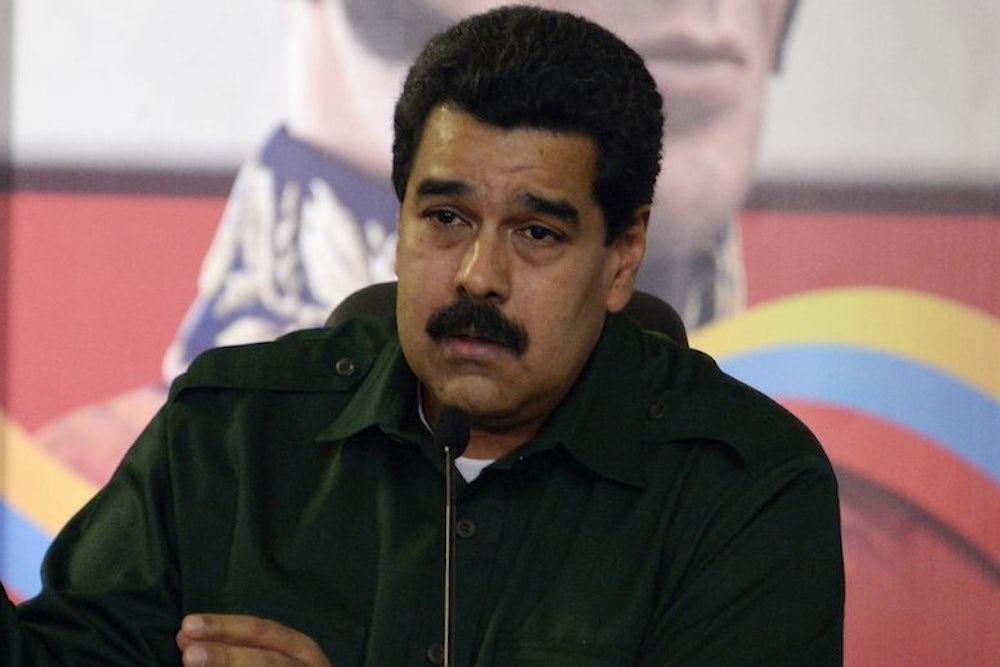

Christmas came early to Caracas this year. “Today, Friday, November 1, we would like to declare that Christmas has arrived!” Venezuela’s new president, Nicolas Maduro, told a crowd of shrieking children in a downtown park last month.

The gift to the Venezuelan people was not exactly selfless. Maduro won the presidency in April in a very narrow election, amid opposition claims of fraud. In its aftermath, government and opposition supporters clashed in the streets. People died. By October, inflation had reached a decade-long high of 37 percent, and there were periodic shortages of basic goods. The government blamed the crisis on a conspiracy by capitalist opponents; economists and opponents pointed toward the more likely cause of government mismanagement, including pork-barrel spending and poor handling of the country’s oil reserves.

So by November, few Venezuelans were in a festive mood—and Maduro feared they would use the country’s many December 8 mayoral elections to express their disapproval. “An early Christmas,” Maduro said, “is the best remedy to [ward off] people trying to cause ruckuses or violence.” And Maduro’s early Christmas wasn’t just rhetorical puff: His government began dispatching “consumer protection inspectors” and soldiers to retail stores to enforce new state price controls on many popular Christmas presents.

Maduro next took to state television to highlight a case of supposed price gouging on stainless steel fridges at the electronics chain Daka. He said the government had detained the managers of the store. Meanwhile, an army general called Daka “bourgeois parasites” and announced that the government had begun a 90-percent-off sale at Daka stores.

“I have ordered the occupation of the chain store and the removal of products from the store, in order to sell them to the people at fair prices!” Maduro said at the televised rally. “Let’s make sure its aisles are empty! Let’s make sure there is nothing left in the warehouses!”

It was the start of Venezuela’s state-sponsored shopping spree. Everyone—government supporters and opponents alike—raced down to Daka outlets to take advantage of the bargains. People fought over the last plasma televisions at the Daka outlet in Venezuela’s third-largest city, Valencia. The general for the defense of the economy said the government had to guarantee every Venezuelan “the right to get a plasma TV, to get the latest refrigerator.”

And in the weeks that followed, the government announced more and more sales. The government would announce it had cut the price of a particular good. It would send inspectors and soldiers to enforce its decree at retail stores. Consumers would line up to buy the goods at the new prices. Soon, there was little left on shelves. Everything from clothes to guitars went for a steal.

By early December, there were still some bargains to be found. At one jeans store near the Venezuelan national assembly, soldiers stood guard in front of a 50-meter long line. Pants were selling for half price.

As the December 8 local elections approached, Maduro’s popularity began to rise. Many disillusioned Chávez supporters returned, and Maduro’s leftist bloc scored a more convincing victory at the polls than its leader had in the April presidential election. This time, few disputed the Chavistas’ wins (although the opposition did carry many important contests, including the mayoral race in Caracas).

“Before [the sales] I thought the government would just cross their arms and do nothing,” said María José Cuervo, a state bank employee, in relation to price rises at goods importers. “But after the measure, I have noticed that they do have plans, that they are working on measures and not just acting on the spur of the moment.”

By the time Maduro’s party won most of the mayoral elections on December 8, many retailers were out of stock. There was nothing left in a Caracas Samsung outlet I visited, for instance. And all the electronics at the duty-free in the city’s Simón Bolivár International Airport had taken off, too. Retail workers were worn out after soldiers and shoppers descended on and depleted their stores.

“Which retailer is going to have merchandise in January? None of us. We’ll go crazy!” said local vendor Alfredo Rivero on Caracas’ Sabana Grande shopping strip. “Do you think that I have a million dollars that I can put into fridges and washing machines? I don’t. So why did they expropriate me and force me to sell at 80 percent off?”

Maduro’s patron, the late Hugo Chávez, also had a soft touch when it came to presents. Chávez, wrote Guardian journalist Rory Carroll in his book Comandante, even created a special government department, the Office of Hope, to sort through supporters’ wishes so he could fulfill them. Over breakfast, Chávez would read through the pleas of Venezuelans and grant some wishes, whether for a new house or an overruling of a bureaucratic decision.

Maduro, then, has simply extended Chávez’s generosity to all. Where once only a few benefited from Chávez’s Office of Hope, whole hoards of eager consumers now have new refrigerators and jeans.

Still, there is one crucial difference between Maduro and his predecessor here: Chávez despised Christmastime. El Comandante condemned the “consumerist madness” of the season. He fretted that all the shopping was making Venezuelans “lose sight of spiritual values.”

This year is the first time in 15 years that Venezuela has celebrated Christmas without its Comandante. Still, many Chavistas here are reassured by the leadership that successor Maduro has shown so far. They even have a new nickname for their president these days: Saint Nick.

Jorge Luis Pérez Valery contributed reporting.