Where Have I Been? An Autobiography by Sid Caesar and Bill Davidson

Fame, wealth, talent, and glory don't guarantee happiness. There needs no ghost come from the grave to tell us this, but should anyone have forgotten, this book provides a useful reminder.

In my time, a handful of people have appeared on the comedy scene who are without peer. If they cancel on you, you can't get someone else just like them. Mike Nichols, Elaine May, Mort Sahl, and Jonathan Winters leap to mind; people whose brilliance makes them unique. Where Have I Been? is about one of that select company.

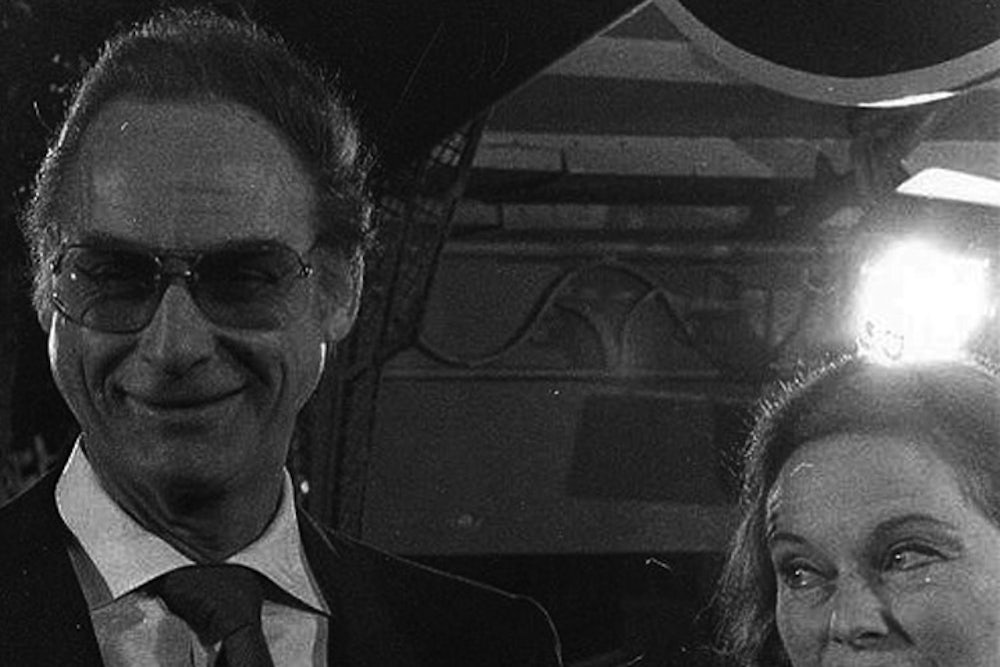

Sid Caesar is a mysterious and complex man who seems to have been singled out by the gods to set two all-time records, one of dubious and unenviable distinction: to have set the high-water-mark for sustained comic brilliance over a long period of years, and to have ingested enough booze and pills to kill the Lippizaner stallions. The twin mysteries of how anyone gets so talented and how anyone could abuse himself so disastrously remain unsolved. To have combined the two and survived is a miracle. And the medal for Heroic Performance by a Wife goes to Florence Caesar.

Many drunks and pill-swallowers can point to a specific moment in their decline when they realize they have hit bottom—that the choice is either the grave or recovery. So with Sid. Our story opens in a depressing make-shift dressing-room (far beneath the noble Caesar's dignity) in a hotel in Saskatchewan where he is doing the play Last of the Red Hot Lovers. Having repeatedly gone up in his lines for the first time in his career and finding himself disoriented onstage, a rattled Caesar is unable to return after intermission. Panic ensues, a doctor is summoned, Sid Caesar asks to be taken to the hospital. He has decided to live. Fortunately for him, and for us, he is here to tell the tale.

I used to hear rumors in the early 1970s that Sid was "in trouble" and there was the mysterious weight loss and the change in appearance that were said to be part of a new exercise regime, but very few people even in "the biz" had any notion of what he was going through. It was a real-life horror show, and a combination of his iron guts and an odd method of self-administered therapy succeeded where the head-candling profession had failed, saving the life of this greatly gifted and tortured man.

In the midst of the nightmare, he continued to work sporadically. During his worst period he even made a movie that he does not recall filming, with actors he dimly remembers meeting, in a country that is a blank in his memory. He is not bad in the movie, and herein lies one of the eternal mysteries: what is performing? What is the mysterious force that possesses the psychically wounded actor-performer and guides him through the shoals of neurosis, physical abuse, fatigue, and dementia so that when the show begins he is, temporarily, whole, functioning, and creative? I have seen (and had) it happen and no one knows how or why. I once worked with a famous actor who had to be supported on both sides coming back from lunch (here gin was the culprit) and who then gave a faultless performance of a ninety-minute live TV play. Something takes over for you. You go on automatic pilot.

I suppose it happens in other professions to a degree, but in the born performer it is a kind of weird miracle, as if other selves exist inside (as with cases of multiple personality in psychiatry) and remain untouched and unaltered by the surrounding chaos, emerging like genies from the lamp and returning when the curtain falls. Although Caesar's professional discipline precluded his showing up drunk for work (he did the damage after hours) this automatic-pilot phenomenon allowed him to work off and on during his lean years after Your Shout of Shows and Caesar's Hour and to acquit himself passably if not brilliantly.

Where Have I Been? contains some fascinating behind-the-scenes stuff including the predictable instances of insensitivity and bungling on the part of the network brains who treated their golden egg as brass, and whose short-sighted greed resulted in more suffering for Caesar and less of him for us. The reader is spared nothing—the rages, the smashed furniture, vomiting on himself in Lindy's and at the dinner table at home, Mel Brooks rescued from being forcibly ejected from an upper-story window, the suffering of Sid's wife and kids—it is all there and is not a pretty sight.

An interesting sidelight is the way in which this book documents another instance of the failure of traditional methods of psychiatry to help the alcoholic and the drug-addicted. On page 164 there is a scene that is well worth the price of the book. An eminent psychoanalyst from whom Sid had sought help for drinking orders him to quit. Somehow, the patient manages to get through the holiday season with only three drinks rather than the three hundred he was more accustomed to. Proudly reporting this to the doctor, he is curtly dismissed and ordered from the office in a manner reminiscent of Otto Preminger playing an SS officer. Sid blows:

I said, 'You didn't look at your watch, Kubie. You see, I've got forty minutes left on this fifty-minute hour, and you're going to sit there and listen to me. You know, Kubie, I never talked about you as a gimp, because I didn't want to make you aware that you're a gimp, a cripple, a nothing, and a man who's got no sensitivity, he's got no time. You've only got time for books—all that crap you put out to the public . . [Kubie orders him out of the office.]

I said, 'Are you going to throw me out? Are you going to call a cop? I'll bury you in the chair there.'

The scene ends with Sid looking at his watch, announcing that his time is now up and Kubie can go count his money. Sadly, Caesar concludes that, despite his blunt insensitivity, Kubie was right; that you stop drinking not with analysis but by stopping drinking.

The above reminds me of an anecdote Mel Brooks tells hilariously about crossing a street in New York with Sid when a cabbie shouted something insulting at him. The window was closed hut the wing was open. After asking him to repeat the slur, Sid asked the man if he remembered his birth. In response to, 'Yeah, what of it?" Sid said, "Because you're about to re-enact it," grabbed the cabbie by the lapels and had him partway out the narrow aperture before cooler heads prevailed.

Ironies abound in the parallels between some of the most famous sketches, tantalizingly recalled in the book, and Caesar's own life. At a recent evening honoring Sid at the Museum of Broadcasting in New York, I sat behind him while the famous "Rex Handsome" sketch was screened (a silent-movie idol fails to make the transition to sound because of his squeaky voice), and marveled at how, despite the broadness of the silly sissy voice he used in contrast with the handsome physique, Sid managed to inject a note of pathos and believability into the sketch. And without Chaplin's tendency to over-sweeten the mix.

if I were making a movie of this, I would put a camera where I was, behind Sid's extra-wide shoulders, as he laughed like a surprised spectator at the antics of the fellow on the screen. Afterward, he remarked on how strange it was to watch himself in a sketch about a man whose career plummets, performed while he was bringing about the same thing in his own life. Pirandello plus.

This book probably will revive the old hoary argument about the link between neurosis and talent: if you cure the one, do you cripple the other? More than one learned volume has been written on the subject. Some artists fear that, analyzed, they will no longer feel the compulsion to work and, further, that their talent is somehow bound up with, if not caused by, the neurosis. Where the idea came from that neurosis can cause talent is anybody's guess. If true, with half the world neurotic, why isn't there more talent? I think the fallacy arises because performers and other artists find escape in their work. Symptom-free, they might not feel the same need to work, but the idea that they couldn't has never been demonstrated to my knowledge, any more than that a man cured of migraines loses his hair. Diana Trilling has written of a "sort of law of negative compensation" that, for example, gave Marilyn Monroe her gifts along with the ruinous personal weaknesses that, combined with the gift, produced her sad fate.

I remember having Sid on talk shows during what I now realize was his "crisis time"—almost winsomely shy as a talker, alarmingly thin, but a "shtarker" when he stood up to perform. But somehow the vital spark was missing. Now, however, he says he enjoys life like a new toy. He has survived the double-barreled ordeals of success and prolonged self-destruction, and the book has the inspirational quality of any good recovery tale. Give it to the alcoholic, the drug addict, and the comic genius on your Christmas list.