When I met David Remnick at his Upper West Side apartment last month, he had just returned from Sochi. It was very much a work trip. In addition to appearing on NBC as an Olympic commentator, Remnick wrote a lengthy piece on Vladimir Putin for The New Yorker, while also fulfilling his duties as editor of that magazine.

An elevator man took me up to Remnick’s multistoried unit, which he shares with his wife, Esther Fein, and their 14-year-old daughter. (They have two other children: one is in college and the other is a photographer.) Before the interview started, Remnick was his usual engaged self—eager to kibitz about The New Republic, the publishing world, Israeli politics. “I would have loved to have lived in Jerusalem,” he told me in his living room, which is stocked with books and includes a ladder to reach the top shelf (which must be 25 feet high).

Since he took over the magazine in 1998, Remnick has also continued to write articles—on Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, Al Gore, and Bruce Springsteen, among others—as well as a book, The Bridge, on Barack Obama and race. And yet when I asked him a question about reporting more from abroad, he deadpanned, “Oh no, I hardly get out of the house these days.”

It is this reputation for humor and self-deprecation with his staff and the press that has, at least partially, ensured the laudatory coverage that greets him everywhere he goes. And is it ever laudatory. Check Twitter after a story of his goes online, and it’s like the Internet has emptied the thesaurus of all words relating to “genius.” In an unintentionally hilarious Port magazine profile in 2011, Nicholson Baker gushed, “He’s smart and quick to laugh, and if you sit in one of the square soft chairs in his office, he remembers things about your life that you barely remember.” “Making it Look Easy at The New Yorker” was the title of a New York Times piece tied to the release of his Obama book.

To his credit, Remnick is aware of how he’s treated, and during the course of our conversation, as well as a follow-up chat over the phone, he spoke at length about his image. We also discussed his most controversial writers, his frustrations with Obama, and why Philip Roth really chose to retire.

Isaac Chotiner: Your latest piece is about Putin and the Olympics—

David Remnick: It’s less about bobsledding than you would imagine.

IC: That’s disappointing. By the way, this is my only question not about Bruce Springsteen.

DR: Much appreciated.

IC: Do you see Putin as a world-historical figure, or something of a blip in Russia’s drift toward less relevance in the world?

DR: I tend to think he will be an important historical figure, yes. He certainly sees himself as one, as the figure who will reassert Russian power and primacy in the modern world. He considered the collapse of the Soviet Union to be the greatest geostrategic catastrophe of our times. Not an ideological catastrophe; he didn’t care one bit about Marxist-Leninist ideology. It was about power.

IC: You mention his lack of Marxist-Leninism. Do you think he has any ideology?

DR: Yes, I do. I think initially there was not an ideology. He is a state builder. It was all about reasserting the Russian state. But what you see since his return to power is a distinctly conservative Russian ideology, which you might call “Putinism.” What is it? It is a dog’s breakfast ideologically. He is capable of quoting Stolypin, Solzhenitsyn, and any number of people from the Russian or Russian Orthodox past, where useful.

The anti-gay law is an aspect of this. In Stalinist times, as Masha Gessen points out, the convenient other was the Jew, or people from the Caucasus, but mainly Jews. For one reason or another, Putin is not hostile to Jews as such.

IC: He is a forward-thinking guy.

DR: He is very flexible there and we all thank him for that. In Russia, the level of homophobia is extremely high, and so there it is.

IC: You wrote your latest piece while in Russia and doing television. One of your writers once said to me that you don’t have sympathy for writer’s block because you write so much.

DR: I have nothing but empathy for writers. Everybody who has got a job like mine, sooner or later there is a cartoon of that person.

IC: A New Yorker cartoon?

DR: More of a caricature. And I am sure there is a cartoon of Jill Abramson. I know what the cartoon of me is.

IC: What is it?

DR: That I write at a preposterous speed and I will let you fill it in. I guess I should I fill it. I get how hard it is to write. Ninety-five percent of what I am doing is reading and editing and dealing with a very, very complicated piece of business. That is more than full time. But I probably write way too fast. The first nonfiction writer who I ever knew was John McPhee. Some small percentage of his class was about how agonizingly hard good writing is.

IC: You took his class?

DR: I did. And, look, some of it in certain people is dramatized and they need that difficulty as a way of getting from A to B. Whatever floats your boat. With writers I try to get them to get the best of themselves.

IC: About your image, your cartoon—

DR: Not that anyone should give a damn about it, but I am aware of it.

IC: We all care what people think of us. You must feel you get good press, largely because you are the editor of The New Yorker. People want to write for you, and they kiss up to you. Do you think about that?

DR: Yes. Look, I went from being a writer to the editor of a magazine in the course of a weekend. It was a strange experience. But the strangeness was not that everyone was laughing at my jokes.

IC: There is a “Sopranos” episode where all the cronies laugh at Tony’s terrible jokes because he is the boss.

DR: Yes, the idiotic joke! But that wasn’t the strange part. The strange part was what you could do. The freedom involved. I remember distinctly that, very early on, we had a short story slated to run in the magazine, and I read it and didn’t like it. And I was reading I Married a Communist by Philip Roth in galleys, and I remember thinking, Why not do this instead? And we did.

I remember a couple months later, there was a hot investigative piece that Seymour Hersh and I had started together. It wasn’t from before, from “B.D.,” Before David. And I was wondering: How does one relay a big story with possible repercussions to the owner? At The Washington Post apparently there had been a covenant between Ben Bradlee and Katharine Graham called the No Surprises Rule. Graham would not wake up and see that they had run the Pentagon Papers. So I called Si Newhouse,1 who I then had a very slight relationship with, and said that we have this story that I think accused the prime minister of Russia of taking bribes from Saddam Hussein. I called him up and said it had been thoroughly checked and the lawyer had read it and I knew who all the sources were. And there was a long pause. Then he said, “That sounds very interesting. I look forward to reading it.” And that was it. And I have never called anyone since. That is not a common thing anywhere. To take that onboard, that freedom, as well as that responsibility—that was a complicated thing to process.

IC: Speaking of Hersh, he claims that the U.S. government’s story of the Osama bin Laden raid is bullshit. What do you say to that given that your magazine ran a piece that relied heavily on government sources?

DR: I thoroughly stand by the story we published.

IC: And his comments?

DR: Look, there is a difference between what people say loosely or in speeches and what we publish. All I can be in charge of is what we publish. I have enormous respect for him.

IC: Hersh wrote a piece a few months back hinting that the rebels were the ones who used chemical weapons in Syria. Why did that run in the London Review of Books and not The New Yorker?

DR: Or The Washington Post. I have worked with Sy on many dozens of pieces and am proud of that work. And a lot of those pieces had the potential to break a lot of crockery. I was willing, and am still willing, to go to the wall with investigative journalism. But if he and I disagree, it is not an easy thing. I hope we will work again together. I hope you will print this: I wish him all the best, and I think he is one of the great journalists of our age.

IC: As an editor, where do you insert yourself most heavily?

DR: The New Yorker is a strange animal. If you went to a random billionaire and said, Here are ideas for a magazine: a non-photograph cover, a long piece on, say, Syria, and yet gag cartoons throughout, I think just the mention of the length would scare potential owners. It is a strange and wonderful piece of business. But I am not picking the poems. I do pick the cartoons. But the reporting aspect, the nonfiction aspect, takes up the most time, both in conceiving and then getting them to publication.

IC: What is your favorite piece of magazine journalism ever written?

DR: There are a number of them that I could name that are extremely expectable, like Talese’s Sinatra or a lot of early Didion or Naipaul—the things that I grew up on. When it comes to earlier New Yorker pieces, there’s a profile that ran in four, five, six parts by S. N. Behrman. It is the most delicious profile of a man named Joseph Duveen, who was both an art connoisseur and also a kind of handmaid to the robber barons. Rockefeller, J. P. Morgan, Frick, Mellon—this generation of Americans who made their fortunes and then wanted to go to the next step of being cultural aristocrats. And they didn’t have any background. So they would go to Duveen, and Duveen would lead them to the art that would allow them to be connoisseurs themselves. Just incredibly funny.

IC: In terms of the business of running The New Yorker, Jane Mayer gave a quote where she said the reliance on contract rather than staff writers was “almost illegal.”

DR: I have never seen that.

IC: I think she was trying to make a point: People are on contract, they don’t have health insurance, they don’t have an office. This is happening with universities, too. And I know your magazine passionately believes in things like universal health care.

DR: Look, Condé Nast limits the number of staff positions. We are fully staffed. So what we try to do with people on contract is pay at a rate that they can make a living, with all that implies, and I hope we are true to that.

IC: Does this trend worry you about journalism?

DR: Again, as far as The New Yorker is concerned, I hope that we pay well and fairly. And I think that certainly goes for Jane Mayer, who has an office and who has now been on book leave for a year. I think Jane would say she is fairly treated by me. But yes, I do not want to create cultural serfdom, on the Web or in print. All I can do is make every effort to be fair and not just market fair. But fair.

IC: I also wanted to ask about The New Yorker festival. Is it a problem that a few months after, say, Ken Auletta profiles Jill Abramson or Tad Friend profiles Ben Stiller, you sell tickets to events with those profile subjects?

DR: What we try to do, and I hope we haven’t made mistakes with any frequency, is keep clear of that. You don’t want to create a situation with coziness or the appearance of coziness. I think festivals are fine. They can be intellectual fun, but they are not the core of what we do. It is an additional thing. But I have to say, I am a bear on these subjects, whether ethics or accuracy.

IC: OK.

DR: To be honest with you, what’s on my mind about business and technology all at once is a much more complex thing than the festival. It is no secret that Condé Nast was a conservative player. I wanted to move quickly on the Web, but you need resources. When we first did things online, we thought we would do them The New Yorker way, with the same level of editing and checking, and quickly saw that couldn’t be done. There was a short period of time where we went to the other extreme. But that was too sloppy and careless. So now we try to find measures so that we’re publishing things online that are decently edited but also have some of the velocity of what the Web can do. It is 2014 for print, but it feels like 1931 for the website, which is to say we are experimenting and finding our way. My job, besides the week-to-week for the magazine, is to one day, somewhere down the line, hand off a healthy, vibrant magazine to someone else.

IC: A vibrant print magazine?

DR: All of it. I can’t tell you what that will be. It depends on how long I last.

IC: But are you confident in, say, ten years, of being able to hand off a print magazine?

DR: Yes, yes. But there is no question the Web audience will grow. I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about that. I am absolutely convinced that there are a large number of readers who want something great. That word reeks of hubris and vanity but why not?

IC: Your rival and former New York Times editor Bill Keller just went off to basically start a criminal justice–focused nonprofit.

DR: My old rival and everlasting friend. By getting my ass kicked by Bill Keller day after day in Moscow, I learned how to be a reporter. I respect enormously what he’s doing. He’s ten years older than I am, and for him to try something entirely uncharted and new and clearly with an impulse to do good in the world is admirable.

IC: You’re really sticking it to him with that ten years older stuff.

DR: Yes—underline, heavily underline.

IC: Do you have the gene to go off and do something risky like that?

DR: Honestly, it’s very far from my mind.

IC: To use the term “brand” that everyone likes—

DR: I don’t like it. Sounds like soup.

IC: You want to protect the brand. But do you ever feel pressure to put celebrities in the magazine? You’ve run a few pieces by Tina Fey and Lena Dunham recently.

DR: I think when the writing is good, I have not a single qualm about it. Woody Allen began writing casuals here. He wasn’t printed because he was a celebrity. Same goes for Steve Martin. We are too young to remember what a celebrity S. J. Perelman was in his time, or Dorothy Parker. Groucho Marx wrote for this magazine.

IC: I want to ask about pop science in your magazine and Jonah Lehrer2—

DR: Look, Jonah Lehrer. Making stuff up is not something that is tolerable. And the Dylan quotes. [Laughs] There is no one in the popular culture who has meant more to me since I heard the song “I Want You” in 1966, when I was eight years old. So the idea that what brought Jonah down was faked Dylan quotes is an irony. But it wasn’t in our magazine.

IC: What I thought was interesting about Lehrer—

DR: I am not going to argue with you about Jonah Lehrer.

IC: OK, but do you think people like Lehrer, who have quick and sellable ideas, get somewhat of a pass and make it quickly without being closely examined? They are salesmen.

DR: Ask me what you want to ask me.

IC: Well, just what you think of the pop science that you publish.

DR: To make the leap that somehow what Malcolm [Gladwell] does leads directly to the ultimately sad story with Jonah Lehrer is itself fake science. The fact that Malcolm is a terrific storyteller and is willing to do this thing that no one else was doing—you may not like it, but there is nothing in my mind fake about it. I find it at its best thrilling. And when he started doing this no one else was. I think Malcolm is an original.

IC: Putting aside—

DR: I am concerned with what I publish. The fact that he has imitators and some of them are lesser is not of my concern.

IC: I want to ask about Obama, whom you have written a lot about.

DR: Who?

IC: Obama. Our first Muslim president, from Kenya.

DR: Exactly.

IC: In your latest long piece about him, I thought it was frustrating how—

DR: I read The New Republic. I know.

IC: He couldn’t answer a question without laying out both sides in a condescending way and lecturing.

DR: I didn’t feel condescended to, and it is not my job to soothe your frustration. It is my job to reflect the way he thinks and speaks. But I share some of that frustration as a citizen. That’s his habit of mind. On the one hand. On the other hand. That is to say.

IC: He has rubbed off on you.

DR: No, I mean those are the locutions he uses. What is the shorthand? Professorial? And that leads to frustration. Here is another frustration: In many ways, his foreign policy is a reaction to his predecessor, who under the rubric of democracy-building was a disaster unfortunately. So why was he elected? The distinguishing feature between him and Hillary Clinton was a speech about Iraq. And he says he came to office to end wars. On the other hand, excuse me [laughs], I wish I could hear a lot more from him about, say, Ukraine, than I have, other than just, “We are keeping out.” I find that . . . [shakes his head, trails off]

One of the things he said was that he didn’t need a George Kennan. What Obama meant was that he isn’t in search of a grand vision, but what he needs are strategic partners. Reagan had Gorbachev, etc. OK, so he feels frustrated in the world he has to deal with, but so what? We know these things are complicated. Let’s begin, in Ukraine, with the fact that [Viktor] Yanukovych was elected! I don’t know what Obama thinks about it! And the complexity of Egyptian politics is beyond dispute.

IC: Right, if you ask him about Tahrir Square, you will get an answer that won’t say anything.

DR: [Grunts and nods.]

IC: Do you hear from him after you write?

DR: Never, never. It’s not like we chat on the phone once a week or ever, but the times that I’ve seen him after the publication of the book, I never heard about it from him, which suits me just fine. The only book of mine he ever mentioned was about Muhammad Ali. I am not so sure the best use of Barack Obama’s time would have been to read a six-hundred-page book about himself.

IC: It is your version of self-Googling if you are president.

DR: Yeah.

IC: If you were condemned to a desert island and could bring the works of either Bellow, Roth, or Updike, which would you take?

DR: Roth. Look, I am eternally grateful for the work of all three. And Herzog, of all the novels that the three produced, may be the best. But I grew up on Roth. I might even have extracurricular reasons. I am from Jersey. I am Roman Catholic. Oh excuse me, I am not. I grew up with these books. They meant and mean everything to me. We are in a period of extended celebration of the work of Roth. Some may find that tiresome. I really don’t.

IC: You don’t buy the misogyny criticism?

DR: I have read those arguments, but no I don’t. What’s amazing about him is that there has been a falling off only of length. He saw a distinct falling off in length and quality in Bellow and didn’t want to repeat the performance. He wanted to go out on top. One thing that is very unusual to sustain in old age is length—to hold a novel or big project in your head for an extended period of time.

Reporting is hard to sustain, too. You are lucky if five percent of what you get is good. It is sitting at the airport, missed connections, and your patience can fall off. I feel it myself sometimes. The temptation is to crunch the reporting process and not give free rein to your curiosity. As a writer I need something in front of me.

[His wife enters the living room and asks for fifty dollars.]

IC: Is that on the record?

DR: The fifty dollars is on the record. Just to finish the thought: I am a reporter. I am not a good polemicist. I write “Comment” but am not that great at it. If I am halfway decent, it is when I report.

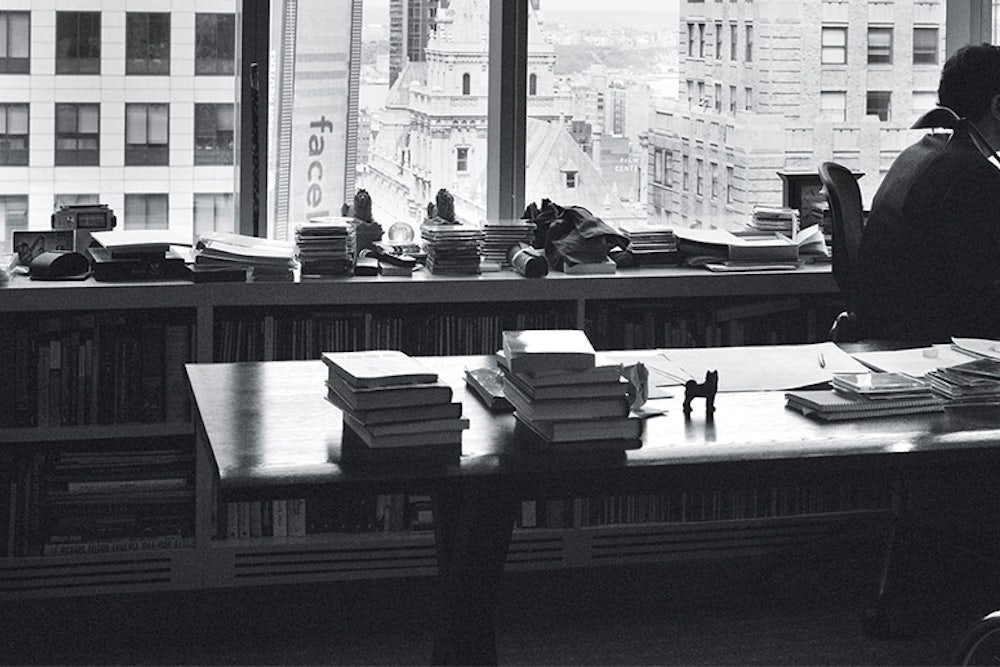

IC: I have this image that in the Condé Nast building there are all these sharply dressed hip people, and then there’s The New Yorker staff.

DR: You mean you think we look like the Waltons upstairs?

IC: I reserve comment on that, but is there a culture clash?

DR: No one has ever cut me off on line in the Condé Nast cafeteria—we seem to be treated like full citizens.

IC: Anna Wintour treats you OK?

DR: More than OK. I have to say, we do a very different thing, but I’ve learned a lot by talking with her about how she does what she does. I once had a conversation with one of her deputy editors—this was early on, and I didn’t know much about her at all, and I think it even preceded the whole wave that came with The Devil Wears Prada. And I asked this person, why is she considered a terrific editor? And she answered: because she knows exactly what she wants. This was a bit of a revelation to me.

IC: Revelation how?

DR: This is the period I was talking to you about earlier—just getting your footing running something. It’s not always a natural thing to know exactly what you want. And I think sometimes when you’re dealing with writers or other editors, God knows if you’re running something larger like a country, Hamlet-like indecision may be interesting, but it’s highly ineffective.

Isaac Chotiner is a senior editor at The New Republic. This interview has been edited and condensed.

The head of Condé Nast, which owns The New Yorker.

A best-selling author who was fired for self-plagiarizing his previous work. He also invented Bob Dylan quotes for his book, Imagine.