The Classical Liberal Constitution: The Uncertain Quest for Limited Government by Richard A. Epstein (Harvard University Press)

When I joined the faculty of the University of Chicago Law School in 1981, there were two defining figures: Richard Posner and Richard Epstein. Posner was the world’s most important voice in the emerging field of “law and economics.” At the time he believed that courts should “maximize wealth.” Epstein, a defender of personal autonomy with strong libertarian inclinations, was Posner’s most vocal critic. At the University of Chicago Law School lunch table, where the faculty ate four times each week, the two had some fierce struggles. Tempers flared. No one who was there will forget those lunches, which sometimes seemed like a form of combat.

Neither Epstein nor Posner had a lot to say about constitutional law; much of their focus was on private law and in particular on the law of torts. Posner had made his reputation with a famous article called “A Theory of Negligence,” in which he argued that under the common law, people who harmed others were held liable, and had to pay damages, only if the benefits of taking precautions outweighed the costs. In an article called “A Theory of Strict Liability,” Epstein took a different view. He argued that if one person harmed another, he had to pay damages, even if the benefits of taking precautions did not outweigh the costs. Epstein made a number of economic arguments, suggesting that strict liability was preferable on economic grounds. But it was clear that he was motivated, in significant part, by a concern for personal autonomy. Epstein seemed to think that if someone hurts you, he has to pay you.

Epstein also produced a brilliant essay on the problem of “nuisance.” In law, a nuisance arises when someone creates an unreasonable interference with people’s enjoyment of their property. Loud noises or noxious fumes can create a nuisance. Epstein explored, and had evident sympathy for, a simple intuitive judgment about corrective justice: if people are injuring you, they have to stop. But he insisted that the real world complicates the use of that judgment. People face various barriers to initiating lawsuits, and when many people are injured by an action, as in the case of pollution, the private law system may be inadequate. But in Epstein’s view, we should always keep in mind the central goals of that system, one of which is to render “to each person whatever redress is required because of the violation of his rights by another.” He contended that it “is possible, both in the pollution cases and in the others that we have considered, to trace the heritage of private law concepts into problems which, solely because of their bulk and unwieldiness, have become the proper subject of the public law.”

In the early 1980s, Epstein was an expert on the law of tort, property, and contract; he did not teach constitutional law. But in view of his work on nuisance, his libertarian inclinations, and his deep skepticism about regulation and regulators, he became acutely interested in the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause, which forbids the federal government from taking people’s property except for “public use” and on provision of just compensation. In 1985, he published a book called Takings: Private Property and the Power of Eminent Domain, which asserted that a great deal of what is done by modern governments is an unconstitutional “taking.” In Epstein’s view, it was worth wondering whether regulations that purport to help disadvantaged people—such as minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws—should be counted as constitutionally dubious “takings.” “It will be said that my position invalidates much of the twentieth-century legislation, and so it does,” Epstein remarked. “But does that make the position wrong in principle?”

Many constitutional law scholars thought that Epstein’s book was eccentric, but it struck a chord. In fact it became a bit of a sensation, at least in libertarian circles. During the confirmation hearings for Clarence Thomas, Joseph Biden, then chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, pointed to Epstein’s book and sharply criticized it. Epstein followed that book with a series of ambitious academic articles and books, essentially arguing that significant parts of the New Deal and the Great Society were unconstitutional. In his view, much of what modern government does is inconsistent with the constitutional plan. Not by the way, Epstein wrote a whole book contending that in key respects, contemporary civil rights legislation is a very bad idea, at least insofar as it forbids discrimination by private companies, who should generally be entitled to make their own free choices.

Most constitutional scholars continue to think that Epstein’s views are eccentric, but his views have had a large influence. Epstein is far too independent-minded to lead or follow any ideological movement, but if Tea Party constitutionalism has academic roots, or a canonical set of texts, they consist of Epstein’s writings. More than anyone else, he has elaborated the view that our Constitution is libertarian, in the sense that it sharply restricts the power of the national government, and against both the nation and the states, creates strong rights-based protections of private property and freedom of contract.

That view hardly commands a consensus, but it is not limited to the law schools. In a speech delivered in several places and ultimately published in the Cato Supreme Court Review, a highly respected judge, Douglas Ginsburg of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, wrote that federal judges were faithful to the Constitution until the 1930s, when “the wheels began to come off.” Among other things, Judge Ginsburg objected that the Court has “blinked away” central provisions of the Bill of Rights, including the Takings Clause, which, he lamented, has been read to provide “no protection against a regulation that deprives the nominal owner of most of the economic value of their property.”

Ginsburg’s colleague, Judge Janis Rogers Brown, has spoken in even stronger terms. She asserts that the New Deal “inoculated the federal Constitution with a kind of underground collectivist mentality.” For Judge Brown, changing interpretations in the 1930s “consumed much of the classical conception of the Constitution.” In this respect, Judge Brown sounds a lot like Epstein, and she is not the only judge who does.

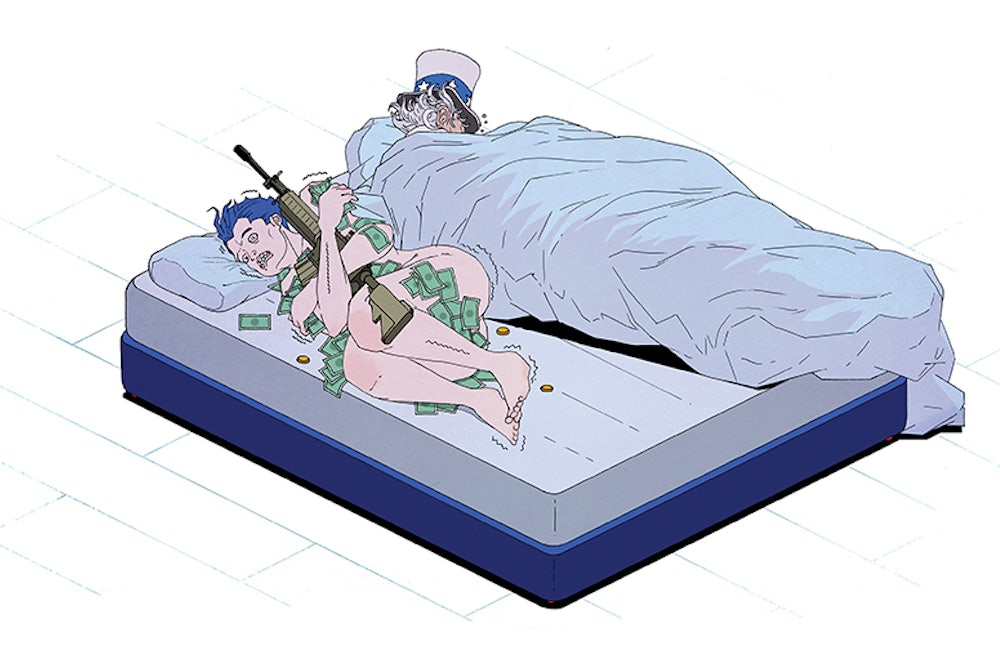

Within the Republican Party we can sometimes find a similar view, especially among “movement” conservatives, often associated with the Tea Party, with prominent politicians and ordinary citizens confidently asserting large claims about the Constitution—and notwithstanding current law, the supposed unconstitutionality of much of what federal and state governments now do. Everyone knows who Rand Paul’s father is, but in an intellectual sense it is Richard Epstein who is his daddy.

Epstein has now produced a full-scale and full-throated defense of his unusual vision of the Constitution. This book is his magnum opus. In a revealing confession, he notes that “in a conventional sense I am not a teacher of constitutional law, having taught the structural course and the First Amendment course once each, and over a decade ago.” But he adds that he has also taught many courses “in which constitutional issues play an integral role,” including “courses in civil procedure, contracts, property, and torts.” This claim is revealing, because those courses sometimes do not touch on constitutional law at all, and when they do, it is usually sparingly.

Epstein is steeped not in American constitutional law but in Anglo-American common law; it provides the foundations for his thinking, and it animates much of what he writes on the Constitution. On his view of the common law, the central ideals include respect for freedom of contract, strong protection of private property, and an individual right to prevent, or to receive damages for, injury to one’s person or one’s things. The set of rights protected by the common law is radically different from the set of rights protected by modern democratic societies. As Epstein notes, he was educated at Oxford in the 1960s, “where my common law education contained no serious discussion of either federalism or the basic structure of the United States Constitution.”

When Epstein comes to constitutional law, he is, in a sense, a stranger in a strange land. That is a big risk, but it is also a potential advantage, because it allows a kind of independence and outsider’s perspective—in his case, the perspective of an outsider who has a particular view of the foundations of private law. When he contends that he aims to defend “with a passionate intensity the classical liberal vision of the Constitution,” he should be understood to be proceeding not as a scholar of eighteenth-century constitutional debates but as an enthusiast for a certain understanding of Anglo-American common law, one that can be connected with important strands in eighteenth-century political thought.

To give content to what he calls (controversially) “the classical liberal vision,” Epstein offers a foil, the villain of the piece, which he calls the “modern progressive” or “social democratic” approach. He identifies that approach with the 1930s, when, he urges, policymakers jettisoned “the traditional safeguards against excessive state power.” As a matter of law, their ill-advised, and constitutionally illegitimate, reforms became possible for two reasons. First, the progressives saw ambiguity in the constitutional text, thus licensing those reforms. Second, the progressives insisted that unelected judges should recede in favor of We the People, acting through elected representatives. Epstein does not deny that the Constitution is sometimes ambiguous. Importantly, he acknowledges that “our basic conception of the proper scope of government action will, and should, influence the resolution of key interpretive disputes.” But he emphasizes that a “detailed textual analysis” has priority over our preferred views about political theory.

Much of his book consists of comprehensive and exceptionally detailed accounts of how constitutional provisions ought to be understood. In many places his discussion is highly technical, but in some important respects—of course not in all—you can take it as a careful and sophisticated guide to Tea Party constitutionalism. He believes, for example, that in interpreting the Commerce Clause, courts should not allow Congress to exercise the broad authority that it now has to regulate private activity on the ground that interstate commerce might be involved. He believes that the Affordable Care Act does not fit with the original constitutional plan, and he has written that “knocking out the individual mandate should be a piece of cake,” but he would go much further. In his opinion, the National Labor Relations Act is unconstitutional insofar as it “did not solve any national problem.” He contends that “one should do everything possible to curtail or at least cut back the affirmative scope of the federal government under the Commerce Clause on the ground that the new powers are chiefly used to create national cartels that are antithetical to the basic provisions of classical liberal theory.”

He also thinks that the courts have wrongly expanded national power through an unduly broad reading of the Constitution’s Necessary and Proper Clause, which grants Congress the power to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States.” Under this provision, Epstein would require a fairly tight link between an enumerated power (say, the Commerce Clause) and whatever Congress does. He objects that the Constitution does not allow for the independent regulatory agencies, operating apart from the president and including the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission. He believes that the National Labor Relations Board is unconstitutional, certainly insofar as its members have the authority to adjudicate.

Epstein reiterates his view that the Takings Clause should be understood to impose far greater limits on the power of the national government. He argues that the Court has taken a far too narrow view of the Constitution’s Contracts Clause—and that certain legal requirements, including some in modern telecommunications law, should be struck down as unjustified restrictions on freedom of contract. He contends that the First Amendment imposes severe restrictions on campaign-finance regulation, and hence that the Court has been right, in recent years, to insist on such restrictions. “A general theory of freedom surely allows any person to spend his or her own money on gaining election,” he writes, and it “is very difficult to find a strong justification for the limits on campaign contributions.” And there is much more.

All of Epstein’s particular discussions are instructive, and most of them are provocative. It is tempting to engage them in detail. But the risk of particularized engagement is that it would lose the forest for the trees. The larger point is that Epstein has a general framework, highly libertarian in character, which he deploys to tackle a large array of problems. He used a similar framework in his early writings on private law. The overlap is no coincidence: a certain conception of classical liberalism, a political theory emphasizing individual immunity from government, lies at the heart of both.

Epstein is quite right to say that if the Supreme Court agreed with him, our constitutional law, and our nation, would be altogether different. We would be a lot closer to what he calls a system of laissez-faire, with a far weaker national government and a more robust set of rights against federal and state interference with private property and contract. To see where his argument is most vulnerable, and where the many people who follow him or concur with him might go wrong, we need to spend some time on the question of methodology. As we shall see, the risk with anything like Tea Party constitutionalism is that it speaks not for the eighteenth-century Constitution, but for the contemporary moral and political views of those who endorse it.

Some people are “originalists.” Originalists usually ask: what was the public meaning of the Constitution at the time that it was ratified? Many originalists think that if the Equal Protection Clause was originally understood to allow sex discrimination, then it still allows sex discrimination. Or if the Takings Clause was understood to apply only to physical invasions of property—and not to regulations that do not amount to any such invasion—then the constitutional question is settled. Justice Antonin Scalia, a card-carrying originalist, believes that ours is a “rock-solid, unchanging Constitution,” and that efforts to see the Constitution as “living” turn our founding document into putty for judges to mold as they like.

Epstein is not an originalist, certainly not in a strict or narrow sense. (Not incidentally, Scalia was also on the University of Chicago Law School faculty in the early 1980s, and he too had strong disagreements with Epstein.) Epstein insists that “in no legal system at any time could the question of construction be reduced to a search for original public meaning of terms that are found in the constitutional text.” In a crucial passage, he acknowledges that “a bare text raises more questions than it answers, which makes it imperative to isolate the general theory that animates the text—usually the protection of personal autonomy, liberty, and property—and then construct the defenses that are consistent with that world view.” In his account, it “is only through the use of a general theory” that hard questions can be answered. He objects that a risk with modern originalism is that “it ignores the relationships between text, structure, and basic normative theory.” Recall, too, his suggestion that “the resolution of key interpretive disputes” will, and should, be influenced by “our basic conception of the proper scope of government action.”

But what is the source of the general theory and “our” basic conception? What does it even mean to say that a general theory “animates the text”? The most convenient answer would come from history. Epstein could have produced a very different kind of book, steeped in the political thought of the late eighteenth century. With such a book, he might have tried to demonstrate such “animation” by carefully linking a theory of the “protection of personal autonomy, liberty, and property” to the particular choices made by those who ratified the Constitution. That would be a highly interesting book, but it is not at all clear that it would be a convincing account of the views of the Founding generation.

In any case, Epstein did not write it. He is much closer to being an Anglo-American political theorist than an American constitutional historian. True, he did not produce his general theory out of thin air. What he calls “classical liberalism” certainly has some connection to the ideas of the great eighteenth-century liberal political theorists, including Locke and Montesquieu, and also to the thinking of America’s founding generation. But we have to be careful here. Epstein’s reading of the theorists and the Founders is not at all obvious or uncontroversial. There are other ways to read them. Many students of the liberal political tradition, such as Stephen Holmes, have raised serious questions about the supposedly libertarian nature of classical liberal theory. It is not at all clear that classical liberal theory, understood in historical terms, is what Epstein thinks it is.

For lawyers and judges, the broader point is that the general theory cannot be found in the Constitution itself. We might doubt, moreover, that as Epstein elaborates it, it would have commanded any kind of eighteenth-century consensus. Without detailed historical support, it remains unclear what it means to say that Epstein’s preferred general theory “animates” the text.

Ronald Dworkin, one of the greatest constitutional thinkers of our time, does not appear in Epstein’s book, but in my view Epstein is playing Dworkin’s game. Dworkin argued in favor of “moral readings” of the Constitution. In his account, the act of interpretation requires judges both to “fit” and to “justify” the Constitution. The requirement of fit imposes a duty of fidelity; judges cannot ignore the text (or other relevant materials). If they do, they are not engaged in interpretation at all. The requirement of justification means that judges should put the Constitution in its most attractive light, by identifying the moral principle or theory that makes the best sense of it. Dworkin urges that judges should be moral readers in the sense that they ought to be generating a morally appealing interpretation of the constitutional text. Inevitably, what counts as a morally appealing interpretation is a product of the active judgments of the interpreter.

Epstein is a moral reader. He objects that progressives ignore the constitutional text, and of course he cares about it, but he acknowledges that on many issues that matter, the text, standing alone, does not mandate his interpretation. Where the rubber hits the road, his real argument is not about Madison and Hamilton, the inevitable meaning of words, or the placement of commas; it is an emphatically moral one. Informed though it is by a certain strand in liberal thought, it reflects what he thinks morality requires. Of course other people think differently. There is an important lesson here about Tea Party constitutionalism as a whole, for the supposed project of “restoring” the original Constitution, or going back to the genius of the Founding generation, is often about twenty-first century political convictions, not about the recovery of history.

Like other moral readings, Epstein’s reading has to be evaluated in terms of both fit and justification. Does it fit with the original document? In some ways it does, but to make a full evaluation we would have to go provision-by-provision, and some of his judgments fit better than others. Most judges want their decisions to fit with precedent as well. Epstein is fully aware that on this count his approach fares poorly, and so he has to answer a genuinely hard question about how to treat precedents with which he disagrees. To his credit, Epstein puts his cards on the table: “In my view, the answer often turns on this simple question: does the original version of the Constitution or its subsequent interpretation do a better job in advancing the ideals of a classical liberal constitution?”

Would our constitutional order be better if judges insisted on moving the nation in the direction of laissez-faire? Would Americans be freer? Would our lives be better? Epstein thinks so. But philosophers and economists have a lot to say on those questions, and there is no consensus, to say the least, that Epstein is right. If we do not accept the libertarian creed (or at least his distinctive version of it), we will emphatically reject his particular moral reading. And even if we did accept that creed, we would have to ask whether federal judges, with their limited place in our constitutional order, should insist on it. Consider in this regard the cautionary words of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.: “If my fellow citizens want to go to Hell I will help them. It’s my job.”

Epstein has written a passionate, learned, and committed book. But he is asking his fellow citizens, and the fallible human beings who populate the federal judiciary, to jettison many decades of constitutional law on the basis of a general theory that the Constitution does not explicitly encode and that the nation has long rejected. Epstein is right to say that in some contexts, a movement toward what he calls “classical liberalism” would be in the national interest. But a judicially engineered constitutional revolution is not what America needs now.

Cass R. Sunstein is the Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard University and the author, most recently, of Why Nudge?: The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism (Yale). He is a contributing editor at The New Republic.