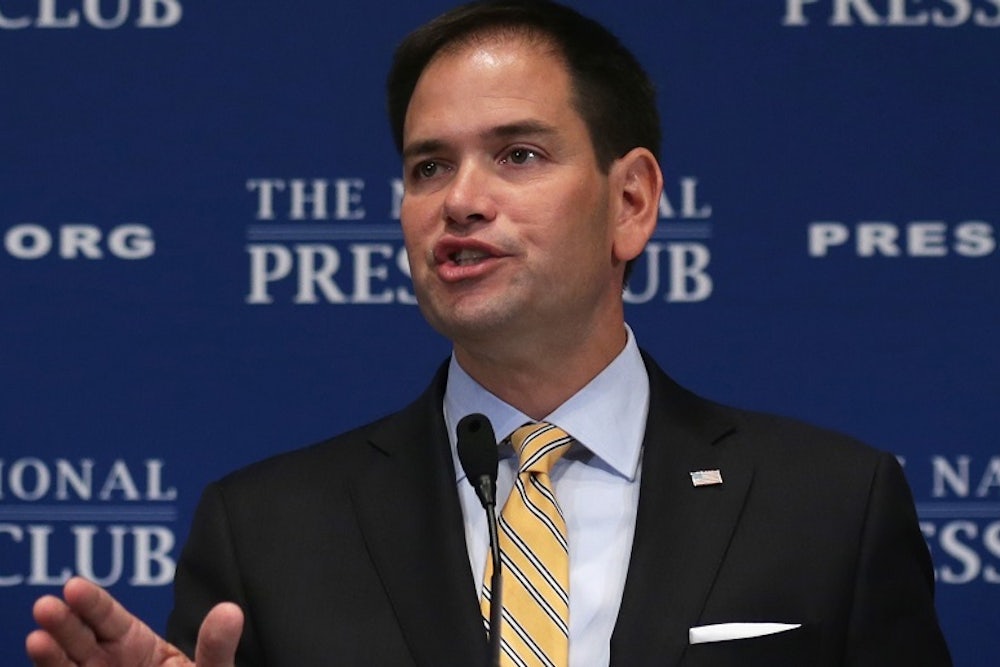

During President Barack Obama’s first term, the Republican Party’s legislative platform was bare. They took their cues from the White House. If Obama endorsed it, Republicans were against it. But during the past year, reform conservatism has undergone a resurgence and few have embodied it more than Senator Marco Rubio.

In January, Rubio unveiled an anti-poverty platform that would radically redesign how the government fights poverty. As I’ve written before, the proposal, as currently described, is mathematically impossible. But Rubio has yet to unveil formal legislative language and there are ways for him to fix those errors—such as by increasing the funding for it.

On Tuesday, Rubio revealed another part of his burgeoning policy platform: Social Security reform. The four parts of his plan all have policy tradeoffs, but taken as a whole, it’s a smart proposal that liberals cannot ignore. Here are the four pieces.

1. Open up government retirement plans to all Americans. For those Americans that cannot take advantage of retirement plans promoted through employers, banks, and the tax code, few institutions exist to help them save for retirement. Government retirement plans, called Thrift Savings Plans (TSPs), are open to all government employees. They have low costs and offer a wide variety of investment options. In fact, the Center for American Progress has endorsed the exact idea. It’s not perfect. As Jason Richwine explains at National Review, there are potential political landmines that could reduce the effectiveness of TSPs, but those are not insurmountable obstacles to the proposal.

2. Eliminate the Retirement Earnings Test. Unbeknown to most Americans, when you choose to collect Social Security benefits early (before the age of 65), your benefits are reduced in the long run. The Retirement Savings Test is designed to force Americans who collect benefits early to save for retirement. Any worker who elects to receive their benefits early is subject to this test. Once their earnings surpass approximately $15,000, their benefits are temporarily reduced by $1 for every $2 in additional income. Those benefits are not lost though. The worker receives larger benefits after they reach full retirement age.

The tradeoff to this forced savings mechanism is the labor market effect of the earnings test. Americans do not realize that their benefits are lost only temporarily. In other words, they treat the earnings test as a 50 percent tax—a big disincentive to work. Rubio wants to eliminate this disincentive by abolishing the Retirement Earnings Test altogether. This would also lead some seniors to collect their benefits earlier, now that the supposed tax is gone. The Social Security Administration’s Anya Olsen and Kathleen Romig found that eliminating the test would lead to increased labor-force participation, but also would slightly increase poverty.

“Those people tend to use up their savings as they get older and Social Security becomes a more significant part of their retirement income as they age,” the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities’ Paul Van de Water told me. “Getting more benefits in the near terms in exchange for getting lower benefits in the longer run isn’t necessarily a good deal for people.”

3. Eliminate payroll taxes for those over 65. For every year a person works after they turn 65, they pay Social Security taxes without receiving any additional benefits from the program. It’s a penalty on work—another feature of Social Security that discourages work. Many economists, including those at the Congressional Budget Office, expect reduced labor force participation to slow economic growth over the next decade. Along with removing the RET, eliminating payroll taxes for those over 65 would be a way to marginally help boost labor force participation among older workers—and increase economic growth.

There are tradeoffs here as well. Eliminating payroll taxes for those over the age of 65 would remove a source of revenue for the program. Rubio could instead use those revenues to fund an expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, for example. That could increase labor force participation even more than his current plan.

“[An EITC expansion], I think the evidence shows, would clearly promote a lot more labor supply than getting rid of the payroll tax above 65,” MIT economist Jon Gruber said. “In some sense, unless you think there’s a particular reason why we want older workers in the labor force, it seems to me that you have to put it in that tradeoff context.”

Rubio may value correcting the work penalty in Social Security more than maximizing labor force participation, but that is a tradeoff nonetheless.

4. Means test Social Security and raise the retirement age for those under the age of 55.

Rubio, of course, recognizes that Social Security in its current form is unsustainable. To strengthen the program, he proposes changing the growth rate of benefits at different income levels. Low-income beneficiaries would have a larger growth rate. The rich would see slower growth in their benefits. Liberals often worry that doing this would change Social Security from an entitlement to welfare program, but the funding shortfall is real nonetheless.

In addition, Rubio wants to raise the retirement age at which seniors can collect benefits, but only for those under the age of 55. Republicans argue that Americans are living longer so their retirement should start later. But that’s only among the wealthy. For the majority of Americans, life expectancy remains the same. That trend may not continue. Middle- and low-income American could begin living longer, providing justification for an increase in the retirement age. But as of now, that hasn’t happened.

Even so, Rubio’s plan is unlikely to close the funding gap, as Kevin Drum points out. If Rubio wants to find another way to do so, he should look at increasing the cap on Social Security payroll taxes. Right now, any income over $117,000 is exempt from those taxes. Rising income inequality has caused more and more of total income to fall above that cap. Raising the cap so that it covers 90 percent of total income (its initial level) would close a substantial portion of the funding gap.

During the Obama presidency, Social Security has rarely been a topic of conversation. President Obama endorsed using chained-CPI to adjust Social Security benefits, but Republicans largely refused to do so. Paul Ryan’s budget never included a proposal to reform Social Security. It only instructed Congress to develop such a plan.

But, as National Review’s Patrick Brennan points out, Social Security’s finances are deteriorating. We still have nearly two decades until the Social Security trust fund runs out, but that time can approach quickly. Social Security reform will become a larger part of the conversation. With the exception of a New America plan to massively expand Social Security—at a cost of approximately 3.5 percent of GDP in 2033—liberals have been quiet on the issue. Given the plan Rubio unveiled this week, they can’t afford to be much longer.