We’ve spent a lot of time fixated on the Tea Party during this primary season, but a possibly more intriguing internal political struggle is now playing out on the left. And you can bet the Hillary Clinton campaign-in-waiting is paying attention.

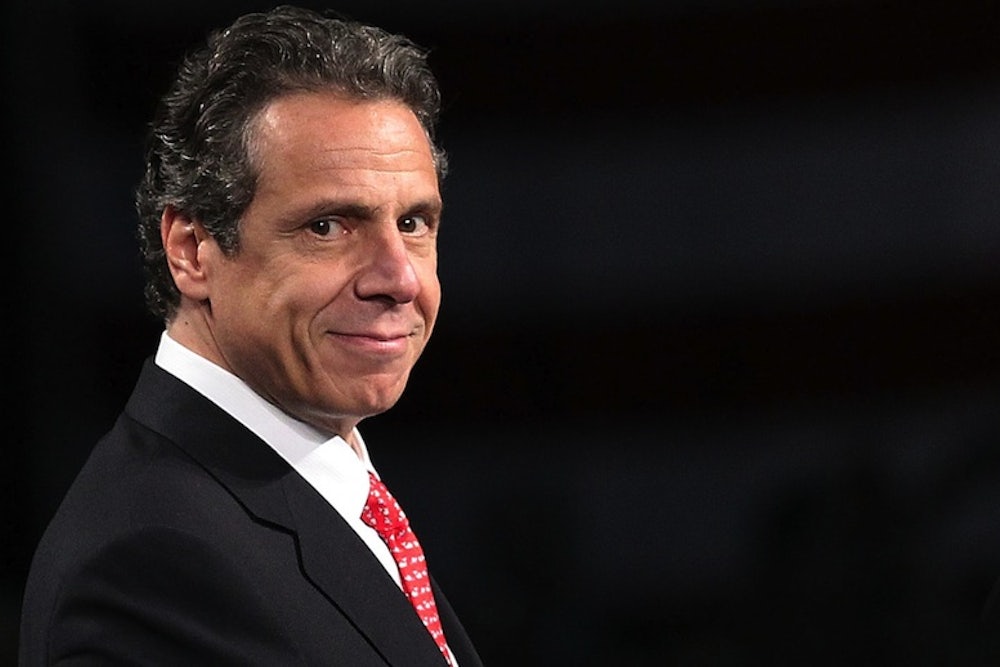

The drama is in New York, where Governor Andrew Cuomo is facing a serious insurrection on his left flank as he heads into what was supposed to be a blissfully uneventful reelection campaign. An increasingly influential third-party in the state is threatening to withhold its support from the governor this fall, which has set off a remarkable flurry of negotiations this week as Cuomo scrambles to keep the group in the fold.

Cuomo’s first term as governor has been defined by his melding of liberal policies on social issues such as same-sex marriage and gun control with far more centrist if not conservative policies on the economic front, where he has pushed tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy. This ideological hybrid has come to dominate the center-left elite consensus of the “Morning Joe”-watching, Acela-riding set, to the consternation of economic populists who wish that bien pensant liberals would get as exercised about rising inequality and stagnating wages as they do about marriage equality. But in New York, at least, there is a social-democratic force in place to push back at concessions to economic conservatism: the Working Families Party, which was founded in 1998 to advocate for progressive policies on bread-and-butter issues and has increasingly become a player to be reckoned with in New York politics.

The party has taken advantage of the fact that New York is one of only a handful in the country with “fusion” laws that allow a candidate to appear on the ballot on the line of more than one political party. This means that a third party can seek to influence one of the two major parties by putting a major-party candidate on its own line, in exchange for some leverage over his or her platform, instead of always just running its own long-shot candidate and potentially playing a spoiler role. The WFP, known for its well-trained operatives and organizers, has had its greatest impact at the municipal level in New York, where it has helped elect a host of city council members who have in turn passed WFP-favored policies such as requiring paid sick-days.

In 2010, the WFP agreed to put Cuomo on its line—he was, after all, the son of Mario Cuomo, one of the great tribunes of economic liberalism, who at the 1984 Democratic convention had eloquently deplored the “tale of two cities” in Ronald Reagan’s America. Elected by a wide margin, Andrew Cuomo proceeded to string up accomplishments—passing budgets on time, winning Republican support in the legislature for the marriage and gun measures, and signing an ethics reform package.

As time has gone on, though, his bent on economic issues has become hard to miss. After initially extending a tax surcharge on millionaires, Cuomo has pushed to raise the exemption for the estate tax above $5 million, cut the state’s corporate tax rate and eliminate its bank tax altogether. His cap on property tax increases means big school funding cuts in many districts. He signed an increase in the minimum wage—to $9 by 2017—but he opposes allowing municipalities to raise it further, and $9 is now looking meager by comparison with increases elsewhere (Michigan’s Republican governor just signed an increase to $9.25 by 2018.) It’s hardly surprising that Cuomo is being rewarded with big checks from Wall Street and the rest of New York’s business establishment—60 percent of his campaign contributions have come in checks $10,000 or larger, while less than one percent has come in donations $250 or below—rates that make even George Pataki, the business-friendly former Republican governor, look like a populist by comparison. Cuomo’s even getting backing from major Republican donors like Ken Langone, the former Home Depot CEO who recently compared liberal worries about income inequality to rhetoric in Nazi Germany.

All of this has been hard to stomach for the WFP, which has been hinting that it might nominate its own candidate for governor at its convention this weekend. (The unions who provide much of the party’s budget—which totaled $7.8 million last year—are largely sticking with Cuomo.) “He is simply not a progressive, especially on the economic justice issues that our party was founded to advance,” says David Schwartz, a member of the party’s state committee and vice chairman of its Westchester County branch. “If progressives in New York can make a real pushback in this election, it can empower progressives around the state to say, enough with these corporatist Democratic policies.”

This might seem like a mere factional kerfuffle, except that the WFP is showing considerable sway in polling on the governor’s race. Two surveys from respected pollsters have shown a Candidate X from the WFP polling above 20 percent. In the most recent one, by Quinnipiac, Cuomo’s vote share plummets from 57 percent to 37 percent if there is a separate WFP challenger in the mix. He still leads Republican candidate Rob Astorino, who is stuck in the 20s in both scenarios, but not by nearly the overwhelming margin he would want to have if he was going to run for president should Hillary Clinton decide not to. (WFP’ers point to Astorino’s low numbers in either scenario to assure themselves that they are not at risk of throwing the election to the Republicans.)

Cuomo allies dispute the WFP critique of the governor, saying that his policies have been geared not toward helping wealthy donors but toward reviving the state’s economy for the good of working and middle-class New Yorkers. Cuomo himself is playing down the tensions: “I’m going to be asking all people for their votes—Democrats, Republicans, liberals, conservatives,” he said on Monday. But he and his associates have spent much of the past few days huddling with WFP officials to dissuade them from a break. In this, Cuomo is getting an assist from Mayor Bill de Blasio, a WFP favorite who has suddenly gone from being the perceived loser in his recent clash with Cuomo over charter schools (Cuomo’s for them, de Blasio not so much) to playing the peace-making power broker.

It is a striking spectacle: a governor with a famous name and $33 million in the bank is scrambling to meet the demands of a third party led by a little-known former community organizer, Dan Cantor, with a mere 40 people on his staff. The WFP has a host of issues it wants Cuomo to move on, but tops among them is bringing New York City’s public campaign financing system to New York state elections, where very loose restrictions have allowed big money (and its attendant risk of corruption) to hold far greater sway. Cuomo has voiced support for public financing throughout his tenure but not brought to bear the leverage he did with same-sex marriage, gun control and other issues to get Republicans on board. He could, for instance, have used the placement of new casinos as an inducement, or threatened to hold up this spring’s budget over the issue, but that would’ve interfered with his claim of passing four straight budgets on time.

Instead, he settled for an exceedingly modest first step toward public financing that applies only to the state comptroller’s race. There are various theories for this. One is that he naturally looks askance at public financing, given that he has been so successful at conventional fundraising; another is that he prefers having a Republican majority in the state Senate, rather than the Democratic majority that public financing might make more likely, because it allows him to cultivate an above-the-fray image and keeps overly liberal bills from coming to his desk. Regardless, his lack of enthusiasm on public financing has been the last straw for many in the WFP, who say they won’t support the governor unless he makes a sincere attempt to pass comprehensive public financing in the final weeks of the legislative session in Albany. “If we had genuine campaign finance reform, and could at least balance the big money and its impact, we’d have a chance to elect a new generation of leaders who could address economic inequality,” says Schwartz.

The WFP’s success is, so far, very much a New York story. But the party has expanded its efforts into Connecticut, Oregon and Washington, D.C., with plans for Maryland, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. It has come to realize that it doesn’t necessarily need “fusion” laws in place to exert influence—instead, it can try to pressure Democrats in primaries, Tea Party-style.

The larger question, of course, is whether the WFP approach could have an impact on Democrats running on the national stage. For now, it’s enough to conjecture that the conspicuous attempt by Hillary and Bill Clinton (Andrew Cuomo’s role model and former boss) to start sounding a more populist theme despite all those capital gains tax cuts and $200,000 speeches to Goldman Sachs is due in part to the WFP drumbeat close to their Westchester home. To Andrew Cuomo’s chagrin, New York is showing the rest of the country what having an organized left with real leverage might look like.