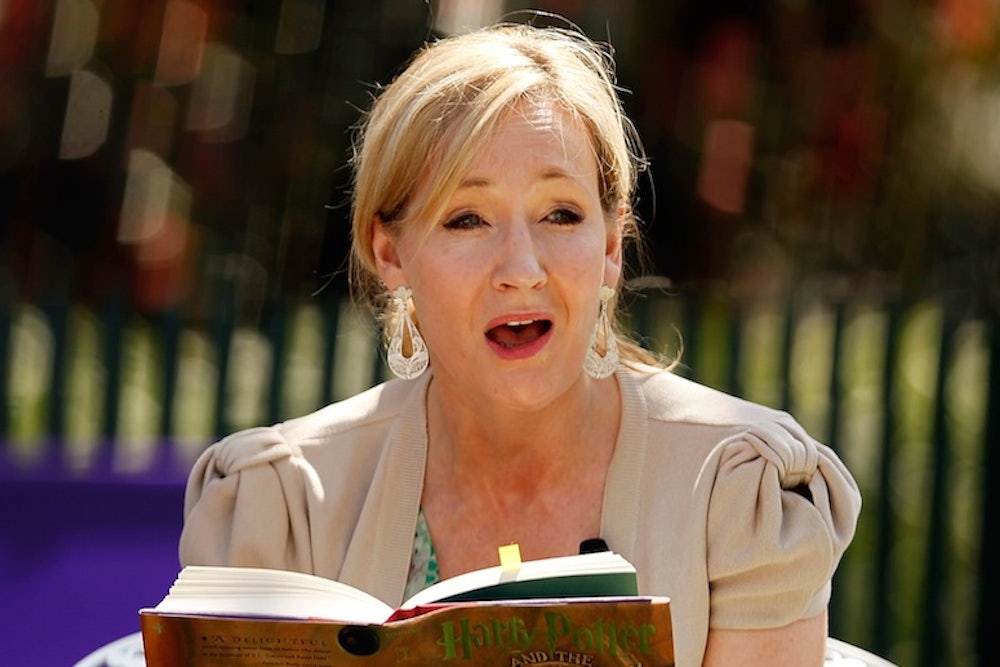

The Silkworm, the second installment of the Robert Galbraith (a.k.a. J.K. Rowling) detective novels, came out last week, and we’re beginning to see a pattern. Critics have noted that Rowling largely writes these novels to form. Even her brooding, war-injured private eye, Cormoran Strike, reads as a recognizable type. But Rowling also makes a significant—and surprisingly overlooked—deviation in her update to the detective genre. Unlike most crime narratives, which unfold in generalized settings—city, countryside, or geopolitical struggle—the Galbraith novels are embedded in niche contemporary subcultures.

Take The Cuckoo’s Calling. The death of supermodel Lula Landry immerses Strike in the world of modern celebrity: paparazzi, coked-up rockers, flamboyant designers, and tabloid nightmares. In The Silkworm, the disappearance of Owen Quine, an eccentric, third-rate writer, unearths the bizarre underworld of the publishing industry. In both novels, solving the murder involves a kind of anthropological investigation of the characters and practices that comprise each subculture. It’s cultural commentary through genre fiction, and since Rowling is one of the most famous and successful writers of our time, it’s hard not to feel like we’re getting the inside scoop.

So what does Rowling really think of the literati?

The line-up of murder suspects gives us a few hints: a boozy editor; a powerful though closeted publisher who retreats to the countryside to paint naked youths; a jealous literary agent whose own writing is “deplorably derivative”; a much-revered but pompous and sexist novelist; a writer of “bloody awful erotic fantasy”; and the victim’s wife, who ignores his books until they have “proper covers.” Then there’s Owen Quine himself, a middle-aged writer riding out his career on a novel published years before—the only decent work of literature he’s produced. Quine is so desperate for adulation that he habitually persuades his mistress to mock-interview him. Even his disappearance is initially disregarded as a publicity stunt to garner attention for his latest manuscript—a thinly disguised exposé of the above figures.

To judge by this cast, it seems that Rowling has a few bones to pick with the literary world. And that’s putting it delicately. Their relationships, as Rowling represents them, are convoluted to a degree bordering on the incestuous. Indeed, the book-within-the-book, Quine’s manuscript, abounds with strange sexual couplings suggesting the depraved nature of their warped alliances turned rivalries turned Jacobean revenge dramas. Rowling’s point seems to be that this is a culture narrowly interbred.

It’s also one of ego-maniacs. And the writers, or would-be writers, are the worst of the batch. When the amateur author of erotica describes her work to Strike in rehearsed phrases and sound bites, he wonders how many people “who sat alone for hours as they scribbled their stories practiced talking about their work during their coffee breaks.” (One wonders: Did—or does—Rowling do this?) Meanwhile, Quine’s agent describes him “as a bigger glutton for praise than any author I’ve ever met, and they are most of them insatiable.” Of course, this agent, a wannabe writer with a first in English from Oxford but no novels to her name, turns out to be pretty insatiable herself.

There’s more than just caricature in Rowling’s submerged criticism. Her reproach of Internet trolls is downright vitriolic: “Hard to remember these days that there was a time when you had to wait for ink and paper reviews to see your work excoriated. With the invention of the Internet, any subliterate cretin can be Michiko Kakutani.” Or the exclamation vis-à-vis online publishing: “The dross the Internet has given us!” But Rowling reserves her deepest anger for the latent sexism of a culture that privileges male authorship. The revered novelist pontificates, “Women, generally, by virtue of their desire to mother, are incapable of the necessarily single-minded focus anyone must bring to the creation of literature, true literature.” A female reader remarks, “What a shit he is.” It’s easy to hear Rowling in that reply.

Mostly, though, Rowling takes pleasure in these caricatures. And one has the sense that she enjoys implicating herself in her send-up of this world—for instance, when the alcoholic editor insists he’s never met a writer “who was any good who wasn’t screwy.” The Silkworm is, at turns, an indictment, a satire, and a parody of literary culture. It offers an outsider-turned-insider perspective of the industry.

In the end, though, the novel is a paean to the struggles of the writer: Rowling uses the idea of the silkworm, which is boiled alive for its silk, as a metaphor for the agonies of artistic production. If writers are sometimes arrogant, sexist, publicity-hungry egoists, they also work magic, spinning beauty and insight out of the blank page.