Houdini is a short strong stocky man with small feet and a very large head. Seen from the stage, his figure, with its short legs and its pugilist’s proportions, is less impressive than at close range, where the real dignity and force of his enormous head appear. Wide-browed and aquiline-nosed, with a cleanness and fitness almost military, he suggests one of those enlarged and idealized busts of Roman generals or consuls. So it is rather the man himself than the showman, the personality of the stage, who is interesting. Houdini is remarkable among magicians in having so little of the smart-aleck about him: he is a tremendous egoist, like many other very able persons, but he is not a cabotin. When he performs tricks, it is with the directness and simplicity of an expert giving a demonstration and he talks to his audience, not in his character of conjuror, but quite straightforwardly and without patter. His professional formulas—such as the “Will wonders never cease!” with which he signalizes the end of a trick—have a quaint conventional sound as if they had been deliberately acquired as a concession to the theatre. For preeminently Houdini is the honest earnest craftsman which his German accent and his plain speech suggest—enthusiastic, serious-minded, thoroughgoing and intelligent.

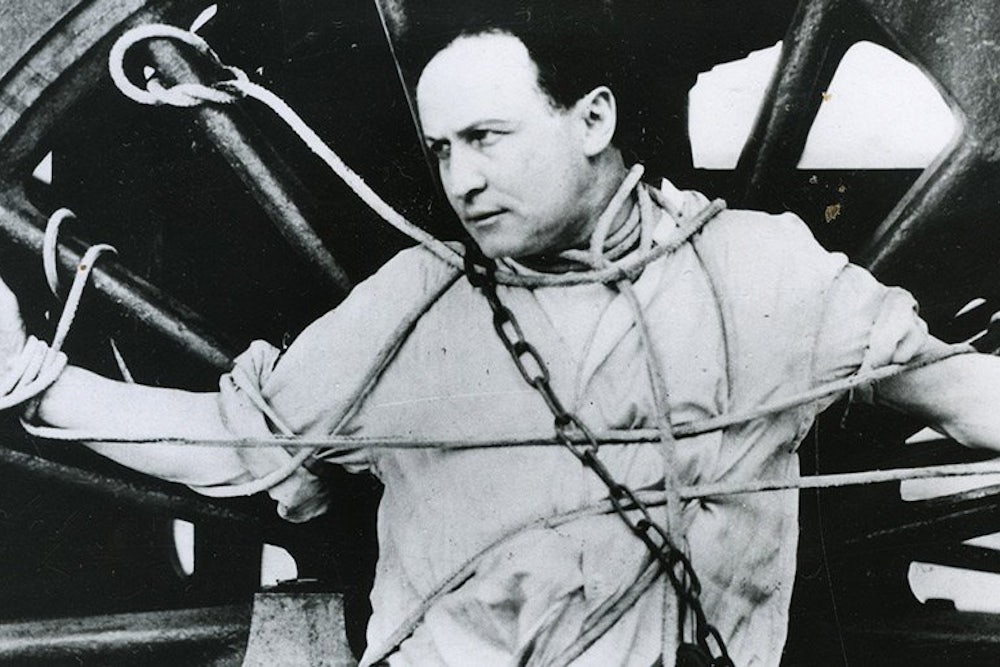

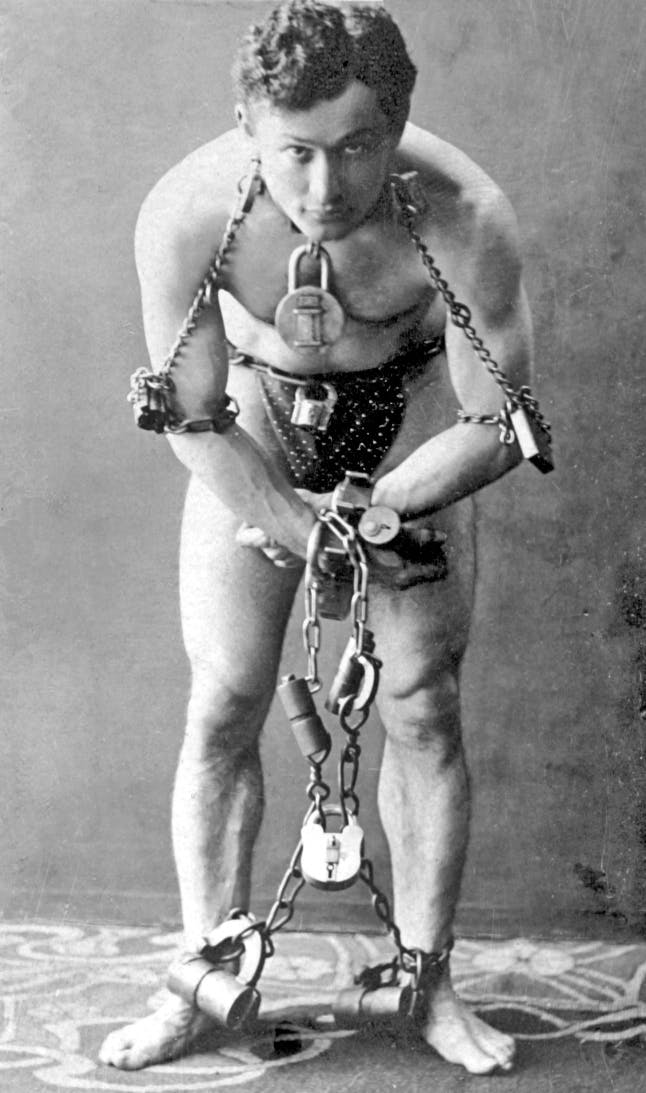

Houdini is in fact a German Jew (Houdini is not his real name)—born in Wisconsin. In his youth, he served an apprenticeship to dime-museums and circuses; acquiring a mastery of the whole repertoire of magic, he eventually took his place, with a show of his own, as a magician of the first rank. Until recently, Houdini has been most celebrated for his cultivation of the “escape,” extricating himself from every conceivable kind of strong-box, straitjacket, hand-cuffs and chains under every conceivable kind of circumstances; and, though this is a department of trickery which has always seemed to the present writer somewhat less artistically interesting than the others, it is characteristic of Houdini that, not content with the ingenuities of illusion and the perfection of sleight-of-hand, he should have chosen to excel in that branch of magic which was most dangerous, which took him furthest from the theatre and which offered most opportunity for the untried. Lately, however, Houdini has achieved a new kind of celebrity in connection with the investigation of spiritualism. Formerly, it was the custom for spiritualistic phenomena to be authenticated by scientists of various sorts and, as a result of this method of research, many surprising discoveries were reported—culminating, at the end of the War, in the ectoplasm revelations. When the French magicians, however, of whose committee Houdini had been made a member, challenged the ectoplasm mediums to admit magicians to their séances, they refused to perform under these conditions. And when Houdini was included in the Scientific American’s committee to investigate Mrs. Crandon, the Boston medium, who nearly won the prize offered by that publication for the production of genuine phenomena, he detected her tricks and constructed a cabinet which made it impossible for her to reproduce them. The truth is, of course, that in a committee of scientists of which Houdini is a member it is Houdini who is the scientist. Doctors, psychologists, and physicists are no better qualified to check up on spiritualistic phenomena than lawyers, artists or clergymen. They are deceived as readily by magicians on the stage as anyone else in the audience and it is equally easy for them to be deceived by magicians as mediums. The problem is whether the medium is a medium or merely a conjuror, and this is something which only a conjuror can find out.

Houdini is thus perhaps the first important investigator of spiritualism who is really competent for the task. He is one of the most accomplished magicians in the world and—what is rare—he has brought to the study of trickery a genuine scientific curiosity: he seems actually now to have become more interested in understanding how effects are produced than in astonishing people with them, and to derive more satisfaction from merely lecturing on the methods of the mediums than in contriving illusions of his own. He has collected a library of books on trickery, occultism and kindred subjects which is said to be the largest in the world; and he has himself published a book on spiritualism called A Magician Among the Spirits and a pamphlet setting forth his observations in connection with Mrs. Crandon and with Argamasilla, a Spanish clairvoyant who claimed to be able to read through metal. He has even been at great pains to expose retrospectively Daniel Home’s celebrated levitation feat of fifty years ago, analyzing the statements of the witnesses and measuring for himself the space between the windows out of one and into the other of which Home is alleged to have floated but which Houdini has now made it appear more probably he navigated by means of a rope. As a result of his study of the supernatural, Houdini has come to the following explicit conclusions: he believes that spiritualism is completely fraudulent because in all the cases with which he is acquainted in which expert witnesses have been called, their testimony has gone against the mediums; he asserts that telepathy is impossible and that he can himself reproduce by trickery any telepathic phenomena of which he has ever heard; that the Hindu miracles of which the legends are always reaching us from the East—the Indian Rope Trick, the stopping of the pulse and the Yogis who allow themselves to be buried alive—are either tricks long understood by magicians or travelers’ stories which have never been authenticated; and that all other supposed supernatural occurrences are to be put down either to coincidence or to hallucination on the part of those who have reported them.

Houdini says that he has never yet been duped, that he has been able to guess all the tricks he has ever seen, but that he lives in continual terror of being outwitted by a telepathist or a medium—in which case his dogmatic denials would be made to look ridiculous. And this has given him a certain edge and excitement as of a man engaged in a critical fight: where he once challenged the world to tie him up, he now challenges it to convince him of the supernatural; and, for all his confidence—sometimes thought excessive—he is keenly conscious of the danger of his position. It may be indeed that Houdini has appeared at a critical moment in the history of spiritualism and that he is destined to play an important role in it. It is difficult for a spectator at one of his Hippodrome performances to see how a credulous disposition toward mediums can long survive public exposures of this kind. Here Houdini reproduces the phenomena of bell-ringing, the floating megaphone and the visitation of mysterious hands in full sight of the audience, who see how the tricks are done, but to the bewilderment of a blindfolded man who sits on an isolated platform with him. When one has seen Houdini possess himself of a megaphone and manipulate it with his head while both his hands and feet are being held, one is not astonished that Mrs. Crandon should have been able to fool the editors of The Scientific American with the same trick in a dark room. And when one realizes that Houdini by resorting to a few simple expedients which he afterwards exposes can tell members of the audience whom he has never seen before, their names, their addresses and facts about their private affairs, one is prepared to believe any marvels of this kind which the mediums, with their elaborate intelligence service, are reported to accomplish.

The real situation, of course, is, however, that among people who frequent séances the difficulty is not for the mediums to convince them of the genuineness of the phenomena but for them to fail sufficiently badly to make their clients suspicious. A professional medium once told a friend of the writer that on one occasion when the séance had gone wrong and he had found it impossible to extricate his hand, he had been obliged to represent the spirit presence by touching the client with his cheek: the medium was in a panic because he realized immediately that he was unshaved; but the lady quickly reassured him after the séance by explaining that she had considered it their most successful: the spirit hand had communicated its divine essence in the form o fan electrical pricking. One remembers also the French savant who reported to his government that, as the result of prolonged and careful researches, he had established in respect to spirits that they had hair, that they were warm, that they had beating hearts, that their pulse could be felt in their wrists and that their breath contained carbon dioxide.