A day after his visit to Ferguson, Missouri, Attorney General Eric H. Holder stated in a press conference that, “History simmers beneath the surface in more communities than just Ferguson.” To what history was he referring? Many assumed General Holder meant the longstanding tensions between the mostly black residents of Ferguson and the mostly white police force, but I believe General Holder meant a deeper and broader history that goes well beyond policing. The anger in Ferguson is not just in reaction to shabby treatment by the police, but also the city’s housing, educational, and other civic institutions.

The history of racial mistrust in Ferguson can be found in the legacy of residential segregation in the St. Louis metropolitan area, enforced from the early to the middle twentieth century through mechanisms such as racially restrictive covenants, zoning laws, realtors agreements, and assessors ratings, as research by Professor Colin Gordon demonstrates. Because of these longstanding policies, black Ferguson residents today are disproportionately renters without a strong political stake in the town’s governance and geographically concentrated in areas without economic power.

The broader perspective can be found by looking to recent events surrounding the school district that serves Ferguson residents. Michael Brown graduated from Normandy High School, which was located, until recently, in the Normandy School District. The facts here are a bit complex, but note that I said “until recently.” That is because the Normandy School district lost its accreditation in 2012 due to dismal standardized test scores. (Normandy was one of only three out of 500 school districts in Missouri to lose its accreditation.) The state school board took over the Normandy School District and renamed it the “Normandy School Collaborative.” By 2013, though, the new district also had lost its accreditation. Missouri law allows students of failed districts to transfer to higher-performing schools in surrounding suburbs, but the failing school district has to pay tuition and transportation costs to get the kids to their new schools. The 1,000 transfer students of Normandy obviously had no desire to remain in the “new” failed district, but the cost was high, so, incredibly, the state board voted to waive accreditation of the Collaborative rather than classify the new district as unaccredited. Ferguson’s teenagers were therefore trapped in a failed school because state politicians didn’t want to pay for them to transfer out.

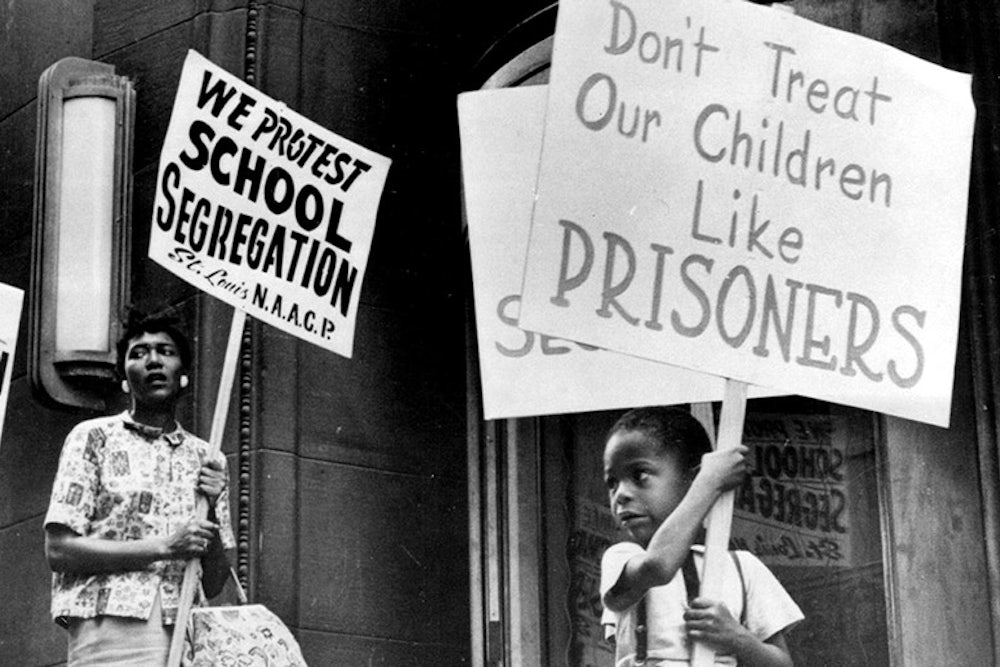

These kinds of shenanigans put the policing of Ferguson into context. The protests we have watched unfold there are not simply about unfair policing in that town; rather, they are the result of a deep and broad collection of official decisions that residents, not surprisingly, interpret as demeaning to them. Viewed in this light the analogies that some have drawn to the riots of the sixties make more sense. The Kerner Commission, charged with investigating urban unrest, hypothesized that conditions in slum living such as poor housing, schools, and jobs fueled the violent reactions of residents, but the reporters also fingered as a prime cause of every riot during the period tensions between police and residents of so-called racial ghettoes. The Commission noted specifically that public confrontations between law enforcement personnel and residents of segregated urban neighborhoods, usually ordinary arrests or stops, as opposed to extraordinary and tragic events like the one in Fergsuon, specifically sparked many riots. Policing incidents may trigger social unrest, but the true foment is deeper and broader.

The lessons that police can learn to prevent incidents such as these also have broader application. My colleague Tom Tyler and I have written that police legitimacy is a key to promoting compliance with the law and better cooperation between police and the public. Decades of social psychological research shows that the foundation of legitimacy is in four components of procedural justice. Legal authorities such as police promote legitimacy by (1) treating people with dignity and respect; (2) making decisions fairly, based on fact and not on illegitimate factors such as race; (3) giving people a chance to tell their side of the story, what psychologists call “voice;” (4) and acting in a way that encourages those with whom authorities deal to believe that they will be treated benevolently in the future. The research is quite clear. People care more about these factors than outcomes. That is, it is often more important to them to be treated with dignity and respect while receiving a negative outcome, such as a traffic ticket, than it is to be treated poorly and not receive a ticket even in a situation where they clearly violated the law. The bottom line? The citizens of Ferguson want to believe that the authorities they interact with believe that they, Ferguson residents, count. Instead, again and again the message the Ferguson residents have received through official action, word and deed is that they do not.

Those of us outside of Ferguson received a lesson in what I have sketched out here when Captain Ron Johnson of the Missouri Highway Patrol came to Ferguson. It is true that his race and the fact that he grew up in the town helped smooth the way for him. It is also true that the fact that he went out and spoke to the demonstrators, listened to them, and explained what he was doing and why are all textbook components of procedural justice. When police authorities act in this way, if a tragic incident such as the shooting of Michael Brown occurs, police executives get a “moment of pause” rather than a riot.

City leaders and the Normandy School board can benefit from a greater commitment to legitimacy in their decision-making as well. Transparency and inclusiveness are keys. I believe that the citizens of Ferguson simply want to be treated as just that—citizens. It is far past time to provide them with what they deserve.