I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because “truth crushed to earth will rise again.”

How long? Not long! Because “no lie can live forever.”

How long? Not long! Because “ye shall reap what you sow.”

How long? Not long!”Truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne, / yet that scaffold sways the future, and behind the dim unknown / Standeth God within the shadow, keeping watch above his own.”

How long? Not long! Because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.

How long? Not long! Because “mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord...”

Those are the concluding words, rising, rising, rising, of Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech from the steps of the State Capitol in Montgomery on March 25, 1965, at the conclusion of the march from Selma. His purpose was to warn against exhaustion in the struggle, to describe a kind of patience on the move, to forestall quietism and despair with the example of his own confidence in the efficacy of historical action. The structure of his peroration was clear: the call-and-response assurance that the results of virtuous exertions are imminent, followed by prooftexts for his faith in the unrelenting push forward. The lines by James Russell Lowell he recited from memory. Only one of his prooftexts, the one about the arc, Obama’s motto, is without quotation marks, because it is King’s adaptation of a more prolix and complicated formulation about the progressive teleology of the moral universe by the abolitionist theologian Theodore Parker in 1853, whose own opposition to quiescence in the face of evil was expressed by his support of John Brown. The context of King’s arc clarifies its meaning. He was not counseling calm. He was not recommending postponement. He was not endorsing acceptance of the existing order of things, even if it was (to borrow Obama’s most recent keyword for impassiveness, uttered again in his tone of weary contemplative detachment) messy. King was America’s greatest critic of resignation. His comment about historical time was designed to prepare his comrades for further hardship in a just cause, and incite them to steadfastness in a grand historical enterprise.

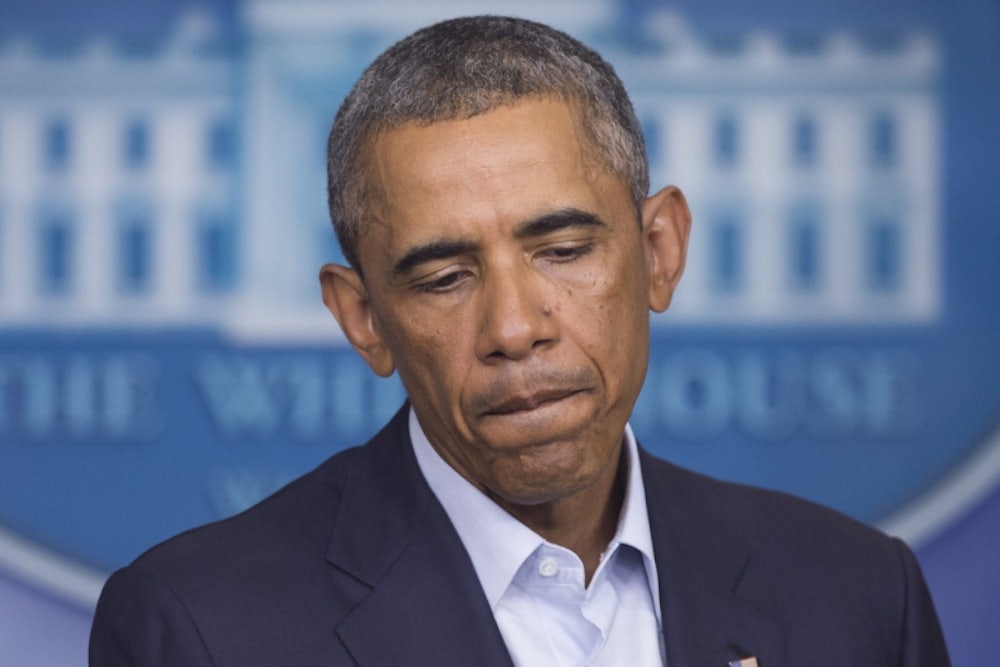

Now Obama has failed in his attempt to slip away from history and its viciousness. The arc has snapped back in his face. It will not let him alone. And so the president is going into the arc-bending business. He has announced his intention to “start going on some offense.” He promises a substantial campaign against ISIS in which the United States will really lead. Its objective is to “blunt,” “degrade,” “shrink,” and “defeat” the Islamic State. The campaign will also include military elements, though “this is not the equivalent of the Iraq war,” as if anybody is asking for the equivalent of the Iraq war. An international coalition has been formed. The president will at last speak to the American people about the urgency of the situation. The White House seems genuinely focused on a struggle toward which it had a genuine aversion.

O happy day, sort of. The White House says also that the campaign may take three years. It is hard not to be bitter about the lost time. For the hideous circumstances that are now impelling us to action were foreseen. In Syria, where the butchery has been unimpeded for three years and Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and his apocalyptics came to flourish, we waited and waited and waited. Two hundred thousand deaths, nine million refugees, and one caliphate later, we can wait no more. Why is arming the Free Syrian Army right today when it was wrong yesterday? (The answer is that it was right yesterday, too.) Is there really nothing about its eternity of dogmatism and diffidence that this White House regrets?

There are lessons here about the temporality of foreign policy. Prevarication is one of the diplomatic arts, but there are circumstances in which the deferral of action represents a misunderstanding of reality or, worse, an abetting of evil. When will American presidents learn that moral emergencies demand logistical efficiencies? There is nothing “impulsive” or “emotional” about the call for prompt and decisive action against certain enormities. Quite the contrary. In such cases, impatience is analytically correct. Interventionists are not less calm than isolationists; we are only more sleep-deprived. Obama recently acted with splendid alacrity at Mount Sinjar and at the Iraqi dams. But one shudders to think of all the innocent people who will die in the next three years. We did not take our time, we took their time. “In this unfolding conundrum of life and history,” King warned in 1967, “there is such a thing as being too late.”

If we are about to reverse our course and undertake the kind of extended diplomatic and military campaign that until a few weeks ago was inconceivable for us, then we must reflect clearly upon the conditions of its success. New varieties of half-heartedness would be disastrous. Shall we not do stupid stuff? Fine, then. Not bombing ISIS in Syria would be stupid stuff. (Where is the border between Syria and Iraq?) Not transforming the Free Syrian Army into a powerful fighting force would be stupid stuff. Not arming—and in every other way standing behind—the Kurds would be stupid stuff. And—here comes the apostasy!—not considering the sagacious use of American troops would be stupid stuff. The obsolescence of the American army is not a conclusion warranted by the war in Iraq. In our determination not to fight the last war, we must not pretend that it was the last war. If the president’s ends in his campaign against ISIS are justified, then he must not deny himself the means. The new government in Baghdad may work out or it may not. Our allies may agree to share the toughest burdens of the campaign or they may not. The outcome of this multilateral effort will depend on the United States. It still comes down to us. Why are we so uneasy with our own moral and historical prominence?

This piece has been updated.