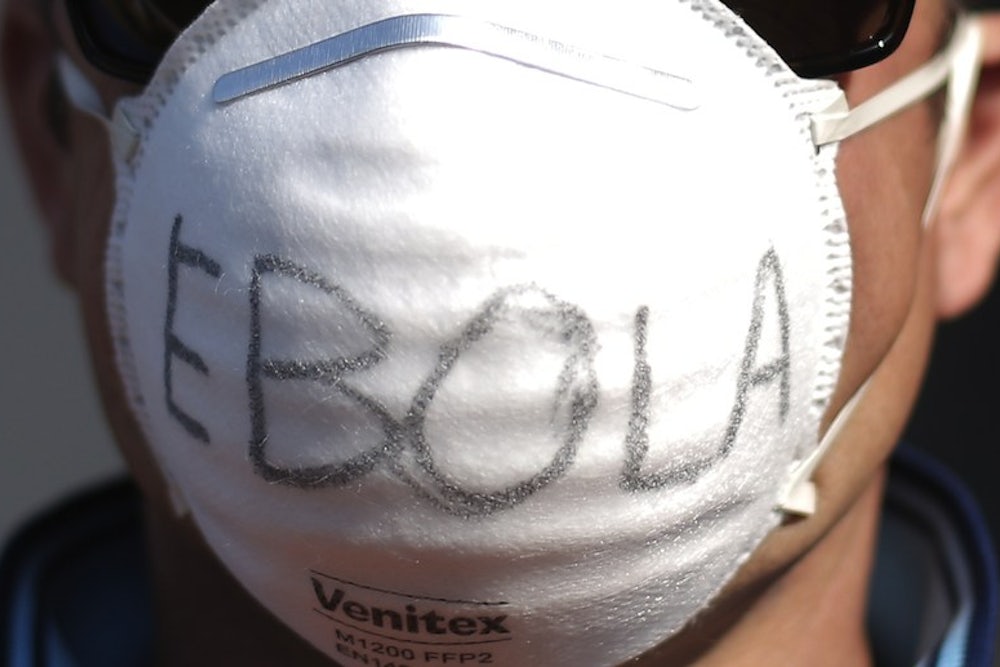

Nearly half of Americans admitted to pollsters that they believe they are “at risk” of contracting Ebola. The effects of the virus go beyond our collective psyche. According to The New Republic’s Brian Beutler, Republicans are gearing up to capitalize on voters’ fear of a massive Ebola outbreak in upcoming elections. And Republicans might benefit from the Ebola panic for another, more existential reason: A growing body of literature in psychology suggests that feelings of fear make people’s political outlook more conservative.

Over the past few years, a number of experiments have begun to shed light on the relationship between emotion and political inclinations. “There’s empirical research that suggests that when people are primed with images of mortality—graveyards, hospitals, the elderly—this can move them to the right,” said John Hibbing, who directs the political physiology lab at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Some studies suggest that people who are already conservative may be extra-sensitive to these images.

Hibbing and his colleagues subject volunteers to stimuli that are either neutral or aversive—some, like images of graveyards or threatening animals, that are meant to evoke fear, and others that are intended to induce disgust. (“The nice thing about disgust is that it’s very easy to disgust people,” Hibbing told me, listing a few reliable stimuli: pictures of “a guy eating worms, a cockroach on pizza, excrement on the street.”) The researchers then ask their subjects questions about their attitudes toward a variety of cultural, political, and economic issues—and the ones who’ve been exposed to the negative stimuli tend to lean farther to the right, especially on social issues. (Disgusting stimuli are especially effective at moving people to the right on sexual issues: opposition to gay marriage and abortion, and support for abstinence-only education.)

Here are two film clips shown to make people more conservative:

The connection between fear and economic conservatism, though, is not as clear. “Economic attitudes seem to be less based on intuitive processes,” said Michael Inzlicht, a psychologist at the University of Toronto. “They seem to be more rational and thought-out.”

In the U.S., of course, cultural and economic conservatism are entwined within a single party. “You may know that if you’re a Republican, you [are supposed to] have certain attitudes about culture and certain attitudes about economics,” said Inzlicht. But that isn’t true everywhere. Inzlicht and a few colleagues gathered data from populations in 51 countries, and found that attitudes typically associated with conservatism—a desire for national security, a high regard for tradition—are generally a reliable predictor of social, but not political or economic, conservative values. So although fear of Ebola is hardly unique to the U.S., right-wing politicians in places like Eastern Europe, where economic and social conservatism aren’t as neatly aligned, shouldn’t necessarily expect the same benefits.

History, too, suggests a link—in the U.S., at least—between a climate of fear and conservatives’ political success. In 2009, Canadian psychologist Stewart McCann looked at the level of “national societal threat”—economic instability, threats from foreign powers—during each period preceding a U.S. congressional election between 1946 and 1992, and discovered that higher levels of national threat corresponded with more wins for Republicans. He found a similar pattern for U.S. presidential elections stretching as far back as the eighteenth century. Another, more recent example is the conservative shift that occurred after September 11th. “After 9/11, people close to Ground Zero—who are among the most liberal portions of the population—moved to the right,” said Hibbing.

Some psychologists believe there’s a biological mechanism underpinning political orientation, which also conditions our response to aversive stimuli. When researchers look at liberals’ and conservatives’ brain scans, conservatives tend to show a greater physiological response to threatening images. If your brain is wired that way, then an increase in conservatism would be a natural reaction to an increase in threat or anxiety. “Conservatism is appealing because it depicts reality as clear, consistent and stable,” said Shona Tritt, a postdoctoral researcher at NYU. “That’s why they might be attracted to policies like lots of spending on defense,” said Hibbing. “It’s perfectly reasonable from an evolutionary standpoint.”

Tritt, though, believes there’s another factor at play: High-emotion arousal states promote what she calls “low-effort thinking.” “It might be that when you’re not thinking things through, you prefer whatever system seems most familiar to you,” she said. “Conservatives tend to prefer tradition to social change.” In a study that was very unpopular with Republicans, University of Arkansas psychologist Scott Eidelman found that people are more likely to agree with conservative ideas when subjected to conditions that don’t lend themselves to deep thinking—like being pressed for time or being drunk.

More recently, though, some researchers have argued that there’s a caveat: It could be that conservatives are not just extra-sensitive to negative stimuli, but to positive stimuli, too. Most of the initial research in this area focused only on the difference between negative and neutral stimuli, but new studies have found that highly positive stimuli, like humorous videos or erotic pictures, can also intensify conservative leanings. This is harder to explain. (And may have fewer real-world implications: How often do we experience massive communal feelings of well-being?) Inzlicht offers one possible explanation: Anything that’s highly arousing may need to be regulated. “If you’re sensitive to these things, you may use political ideology as a way to regulate emotions.” There are, of course, countless factors at play when voters pull the lever—but every psychologist I spoke to thought plausible that Ebola panic could swing voters to the right.