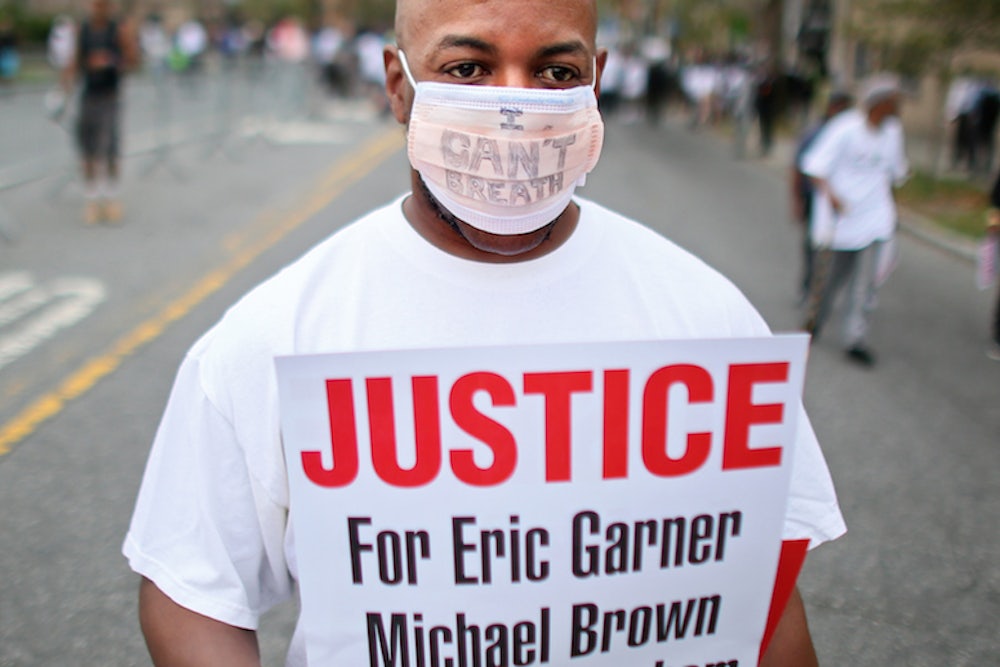

Many of the people who took umbrage at the public outcry over a St. Louis County grand jury's decision not to indict Darren Wilson—the now-former police officer who killed Michael Brown in Ferguson—cited the endless ambiguities surrounding that incident as evidence that the system had worked as intended.

They can’t make that argument about the killing of Eric Garner because no such ambiguities exist. To their credit, they don’t try. Nevertheless on Wednesday, a Staten Island grand jury, empaneled by the Staten Island district attorney, decided not to charge the police officer who put Garner in the chokehold that ended his life.

Even if the Ferguson outcome didn’t strike you as evidence of systemic problems, then Daniel Pantaleo, the officer who killed Garner, getting the same treatment as Wilson should leave you shaken. These are daunting problems. And because they’re daunting, they generate outpourings of unfocused indignation, aimed generally at racial inequities in the criminal justice system and at the culture of impunity in which so many police officers seem to operate. This is natural and important and healthy.

A white man in Garner’s shoes probably would’ve walked away from that confrontation, and the video footage of the incident, taken in plain view of the officers, suggests that even if Pantaleo had been wearing a camera, it wouldn’t have pierced that culture of impunity.

This points to something alarming—that, as Ta-Nehisi Coates of The Atlantic keeps stressing and stressing, the problems themselves in some ways just reflect public will.

And this isn't the fault of police. Police act at the society's behest. Police don't need retraining. America needs retraining.

— Ta-Nehisi Coates (@tanehisicoates) December 3, 2014If that weren’t true, then police wouldn’t be so much more likely to escape indictment than civilians. The disparity would narrow.

And if Coates is right, then at least some of the effort expended on making police officers wear cameras has been misdirected. It should be redirected toward the source of the impunity, which isn’t the quantity or quality evidence, but the officials that so freely disregard it.

If prosecutors and police departments are too tightly linked for due process to mean anything, then puncturing the impunity requires breaking the link.

One way to do this would be for citizens at state and local levels, through ballot initiatives, to take the authority for presenting evidence of police misconduct to grand juries out of the hands of local prosecutors. That authority could be handed to publicly accountable review boards staffed with civilian lawyers from within the jurisdiction, or to special prosecutors’ offices.

The point would be to eliminate the conflict of interest that arises—as it did in Ferguson and Staten Island—when local prosecutors investigate the officers on whom they rely for evidence, cooperation, and political endorsements.

“I think it’s viable,” Ronald Wright, a distinguished professor of criminal law at Wake Forest University told me by phone Wednesday evening. “You could revise state law so that you could describe the category of cases where the appointment of a special prosecutor is mandatory. The governor shall appoint a special prosecutor in the possible criminal wrongdoing by police officer in jurisdiction with the same boundary as the district attorney. You could have an automatic trigger.”

Marc Miller, a criminal law specialist and dean of the University of Arizona college of law points out that the Hawaiian state constitution provides for an independent counsel for grand juries. Though governors and state attorneys general often have wide latitude to intervene when conflicts of interest arise at the local level, making it mandatory in specific cases would eliminate the conflict of interest rather than leave it at the whim of a distant elected official.

The logic becomes clearer when you imagine that a mayor, rather than a police officer, committed the alleged crime. “If there are allegations of wrongdoing by a mayor of a city in the same jurisdiction as the district attorney, the presumption is either that they’re political enemies or political allies, and the relation will cloud judgment about criminal charges,” Wright said.

Instituting systems like this in cities across the country wouldn’t amount to a frontal assault on the vast racial disparities in communities like Ferguson. But it's a concrete goal—one that would give at least some vulnerable communities greater confidence that police wrongdoing will be investigated in an unbiased way. And it would put police on notice that their conduct will be subject to legal review by representatives of their communities who don’t work hand in glove with them.