The ancient Buddhist concept of mindfulness has been gaining traction in secular Western culture for decades, but it may have reached a peak in 2014. “Mindfulness”—understood today as a state of being aware in the moment, and honed through regular practice of meditation and breathing exercises—is widely believed to confer benefits both spiritual and material. In just a few minutes a day, it’s said to help practitioners cope with practically every facet of modern life, from everyday stress and anxiety to life-threatening illness and depression. It’s penetrated many of our major institutions, from hospitals and schools to the corporate world. In Britain, the NHS funds mindfulness seminars for patients with depression. It’s on the curriculum at schools across the country. Companies like Target and General Motors have started offering employees mindfulness training; even cut-throat firms like KPMG and Goldman Sachs have sponsored mindfulness seminars in recent months. Google hosts “mindful lunches,” taken in silence save for the ringing of bells.

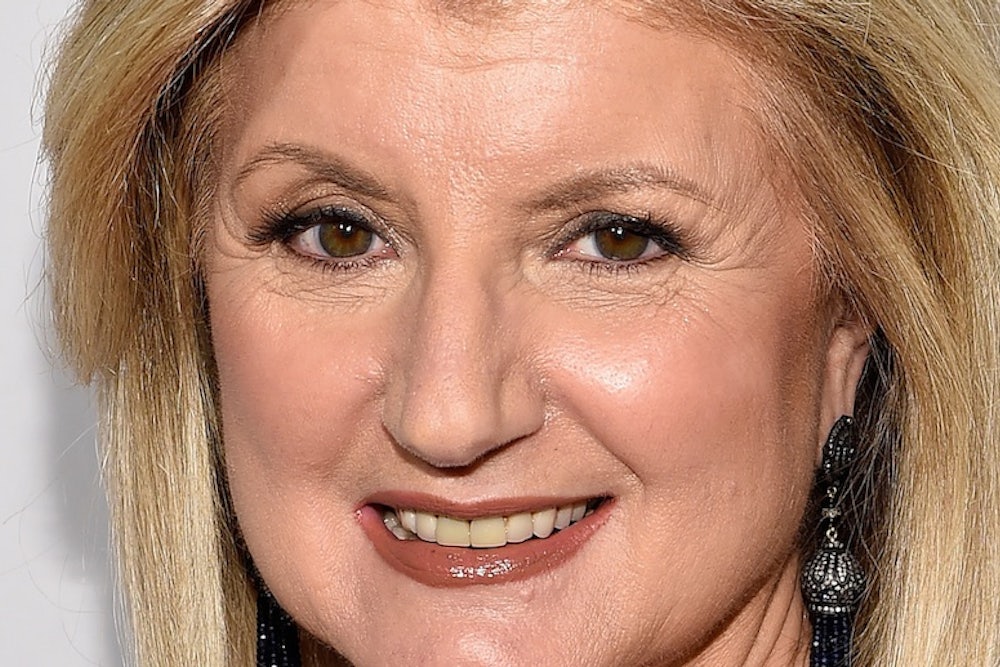

In February, “The Mindful Revolution” made the cover of TIME, and writer Evgeny Morozov labeled "mindfulness" "the new 'sustainability': no one quite knows what it is, but everyone seems to be for it." In March, Hip Hop mogul Russell Simmons published his own guide to meditation. In April, “Nightline” co-anchor Dan Harris’s guide to mindfulness, 10% Happier, reached number one on The New York Times bestseller list. Harris poses as a skeptic who can’t help but acknowledge, after considering the vast scientific evidence, the transformative power of mindfulness. Around the same time, Arianna Huffington extolled the benefits of mindfulness in her self-help memoir, Thrive.

If one person has emerged as the year’s mindfulness guru, it’s Huffington. Thrive uses Huffington’s own story as a starting point: In 2007, the exhausted Huffington—overworked and obsessed with her fledgling media empire—fainted and broke her cheekbone on her desk. Her collapse spurred the realization that the dominant metrics of success—money and power, according to Huffington’s interpretation of our culture—neglect important facets of self and happiness. As she recovered, she came to believe that well-being, which she dubbed the “third metric” of success, is best achieved through mindfulness and meditation. She’s developed mindfulness advocacy into another facet of the HuffPost brand, hosting “Third Metric” events around the world and launching a new HuffPost vertical devoted to celebrity endorsements of meditation and the latest mindfulness research. (Anyone who follows The Huffington Post on Twitter knows that the answer to, “What one thing does this incredibly successful person do every day?” is pretty much always “meditation.”) Mindfulness has fostered unlikely friendships: She and Kobe Bryant traded meditation tips in a New York Times Styles piece in June.

How did mindfulness go from the domain of Buddhist monks to the stuff of puff pieces and New Age proselytizers? According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “mindfulness” (well, “myndfulnesse”) dates to 1530, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that it took on its current associations. “Mindfulness” is a translation of the Pali term “sati,” which originally meant “memory” or “remembrance.” Before the term “mindfulness” caught on, the idea was sometimes translated as “contemplation” or “meditation.” The de-coupling of mindfulness and meditation from their roots has been underway since long before 2014. As Buddhism scholar Jeff Wilson documents in his new book Mindful America: The Mutual Transformation of Buddhist Meditation and American Culture, mindfulness and meditation were not, traditionally, a part of the regular practice of ordinary Buddhists; two thousand years ago, they were mostly the concern of ordained monks, and even for them, mindfulness constituted just one component of a larger (and all-consuming) process of striving for enlightenment. Somewhat ironically—given mindfulness’s reputation as a self-esteem booster—it was part of a project to escape the self and renounce the material world.

In the nineteenth century, small groups of Buddhists in East Asia began to revive the practice—a “reaction to the changing world situation of Western colonialism and imperialism,” according to Wilson. These movements offered a less ritualistic, more personal form of Buddhism—a kind of spirituality that was attractive to visiting Westerners. Interest in Buddhism and meditation in America was sporadic in the first half of the twentieth century, but with the post-war growth of higher education and the founding of religious studies departments, more Americans began learning about Buddhism. As immigration laws loosened in the 1960s, more Buddhist monks came to America, where some taught college courses and established their own training programs and religious institutions.

In the 1970s, Jon Kabat-Zinn—an American who studied mindfulness with Buddhist monks at MIT—brought the practice to the medical establishment, adapting it into a new technique he called “Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction,” or MBSR. MBSR offered patients suffering from chronic pain and stress an eight-week course based on Buddhist meditation; Kabat-Zinn defined mindfulness as “moment-to-moment awareness … cultivated by purposefully paying attention to things we ordinarily never give a moment’s thought to.” Bill Moyers covered MBSR in a 1993 PBS special. Doctors and academics took note. Wilson calls the 2000s the “crossover decade”—the period when mindfulness, with the help of the Internet, shed its association with Buddhism altogether and was appropriated for thoroughly Western contexts like dieting. A google n-gram shows the incidence of the term “mindfulness” in English texts rapidly increasing throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

From ISIS to Ebola to Ukraine, 2014 gave us plenty of reasons to want to escape the present moment. Mindfulness was already catching on, but circumstances helped it explode this year—and celebrities like Simmons and Huffington were poised to capitalize on it. At the same time, new apps like HeadSpace, Simply Being, and Buddhify 2 made mindfulness available on the same devices giving us the (disastrous) news.

There has been some push-back, too. In The Spectator last month, Melanie McDonagh reminds of us its Buddhist roots and criticizes its preponderance in secular environments like public schools. In The Atlantic this summer, Tomas Rocha argues that, for people of a certain disposition, meditation can be dangerous. He tells the story of "David," who went on a meditation retreat so life-changing it totally threw him off track: After experiencing what he describes as an “orgasm of the soul,” he turned down law school, stopped talking to his friends and spent years—and most of his savings—traveling back and forth to Asia, unsuccessfully seeking to recreate that feeling. If 2014 was the year of mindfulness, 2015 might be the year of the backlash.