Legacies are never simple; they create victims as well as beneficiaries. The more substantial the legacy, the more heated the disputes are over who has title of ownership, who gets to enjoy an inheritance, and who is left out in the cold.

One of the most dangerous ways to treat a legacy is to bask in past achievements and revel in riches earned by others without awareness that they came with costs. This shallow legacy-enjoyment is evident in the cheaper sort of nationalism, which glories in a country’s conquests without thought as to the suffering entailed.

The phrase “legacy of racism” encapsulates in a few words a large reality: Bigotries can have complex, ongoing ramifications. Few, if any, longstanding institutions have been historically free of racism. Given the pervasiveness of racism in the past, the struggle to understand this legacy and figure out how to overcome it remains a political and institutional imperative.

Over the last few months, following The New Republic’s centenary anniversary and a staff shake-up, a perceived legacy of racism in the magazine has been the topic of intense arguments, mostly carried out online. In the wake of the debate, vexing questions demand answers: How do we reconcile the magazine’s liberalism, the ideology that animated the Civil Rights revolution, with the fact that many black readers have long seen—and still see—the magazine as inimical and at times outright hostile to their concerns? How could a magazine that published so much excellent on-the-ground reporting on the unforgivable sins visited upon black America by white America—lynchings, legal frame-ups, political disenfranchisement, and more—also give credence to toxic and damaging racial theorizing? And why has The New Republic had only a handful of black editorial staff members in its 100 years?

The New Republic owes an accounting to itself, its critics, and its readers; an honest reckoning on where it has gone wrong is the necessary first step to figuring out how to do better. This self-appraisal is urgent on a number of grounds: A magazine that is loyal to the traditions of liberalism has to account for its occasional betrayal of liberal ideals; honest and pointed criticism, of the sort the magazine has received, deserves a straightforward answer; and finally, as The New Republic reinvents itself in its second century, the lessons of the first 100 years demand attention. Returning to the beginning, we can answer the question: How can this magazine—or any legacy institution—come to terms with a blighted legacy on race and transcend it?

The New Republic was born in 1914, a moment when African American politics was polarized between two giants, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, both of whom contributed to the magazine in its first few years. Washington, the most influential black leader of the early twentieth century, was an advocate of conciliation verging on capitulation. He pushed for a grand bargain with white America, whereby blacks would accept the status quo of the Jim Crow South—segregation in schools, restaurants, public places, public transportation and so forth—in exchange for economic development through industrial education, in schools such as the Tuskegee Institute, which Washington helped found. Du Bois, the first black person to get a doctorate from Harvard, was the insurgent. Through the NAACP, which he helped establish in 1909, Du Bois was an advocate of full civil rights, political participation, and a black educated class.

For at least the first six years of its existence, under founding editors Herbert Croly, Walter Weyl, and Walter Lippmann, The New Republic adopted Washington’s outlook on race as its own. One problem with Washington’s approach, especially as filtered through the magazine’s privileged white writers, was that it framed justice for black America in terms of what was good for white America. Calls for civil rights were often tempered by assurances that fundamental dividing lines such as intermarriage and residential segregation would not be touched. The magazine’s editors thought they were taking a progressive attitude toward race. However, articles calling for cooperation often ended up justifying racism, as in a 1915 piece by one Louis B. Wehle, a Kentucky lawyer and friend of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who argued, “The negro, as a mental survival from slavery, cheerfully accepts the idea of his social inferiority; his problems are born of his shiftlessness, slack morality, and propensity to crimes of violence.” Likewise, a 1920 review of Herbert J. Seligmann’s The Negro Faces America cautioned, “At a time like the present, when race prejudice is peculiarly active throughout the world, we expect a responsible writer to avoid aggressive insistence upon race equality and the right of intermarriage, to accept a considerable degree of race prejudice as irreducible.”

Washingtonian politics meant placing a naïve faith in the power of cooperation. A 1916 report in the magazine on African American education ended with this homily: “In suggesting his program for the further development of Negro education, Dr. Jones places justifiable confidence in a growing spirit of fair play and increasing broadmindedness on the part of the South. The Negro problem is a problem of the democracy and it cannot be solved without the cooperation of the South, the Negro and the North, inspired with ‘an abiding faith in one another.’”

By the mid-’20s, however, The New Republic's commitment to Washington’s strategy of compromise was running aground on the shoals of brute reality. The murderous race riots that followed World War I were a jolt, as was the rise of the Second Ku Klux Klan. “Why in America, more than any other country, do we have race riots, mobs, lynchings, burnings, and manhunts generally?” the sociologist Robert E. Park asked in 1923. Throughout the ’20s, the magazine slowly adopted Du Bois’s call for full civil rights. The 1931 Scottsboro case, where nine black teenagers were falsely accused of rape and eight of them were initially sentenced to death by an all-white jury, became a cause célèbre with the magazine. “Whatever the decision of the Supreme Court in the present appeal may be, the innocence of the nine defendants has long since been established in the minds of all fair-minded people who have followed the trials and know the facts,” the magazine declared in a ringing 1934 editorial. “It is a record of brutality, chicanery, violence and injustice on one side … and of determined, unremitting and courageous struggle for justice on the other.”

This shift in The New Republic toward a more rigorous accounting of racial injustice was coupled with a curiosity in black culture, spurred by the magazine’s location in New York and proximity to the Harlem Renaissance. Readers were served reviews of black theater, fiction, spirituals, and jazz—performances that rarely got such alert attention in other white venues. In 1926, Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant provided a long portrait of Paul Robeson, locating his masterful revitalization of spirituals in his double consciousness as a black man in America. The following year, a searching essay by Wallace Thurman called out works that “treated the Negro as a sociological problem rather than as a human being,” anticipating future essays by Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin.

Still, The New Republic’s discussion of African American culture was punctuated by a jarring insouciance, particularly in the work of white writers. Throughout the first two decades, white writers would throw around the n-word with the casual aplomb of characters in a Quentin Tarantino movie. In 1916, travel writer Harrison Rhodes opined, “We should not be so pleasant a people nor so agreeable a land were the niggers not among us … both the devil and the black man should get their due.” Rhodes thought he was writing as a friend to blacks, whereas he ended up replicating the very racism he thought he was challenging.

“Niggers can be admired artists without any gift more singular than high spirits: so why drag in the intellect?” Clive Bell, the Bloomsbury critic (and brother-in-law to Virginia Woolf) argued in 1921. In 1928, assistant editor T.S. Matthews, who would go on to succeed Henry Luce as editor of Time and marry the war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, shared an anecdote about “a big, young, shiny-black buck nigger” riding a train.

This type of language was partially a literary affect. The magazine was trying to be modern, vernacular, and street smart. But on a deeper level, the magazine’s writers seemed to be going out of their way to assure readers that while they took up the cause of political parity between the races, they weren’t so naïve to accept blacks as social equals.

The pathology of this dual-mindedness is evident in an impassioned 1933 report on the Scottsboro case, by the Louisiana-born novelist Hamilton Basso, in which he noted in an aside, “There is something comic about a Negro who looks like an ape.”

Another distinguished writer who played contradictory roles in the magazine’s legacy was the literary critic Edmund Wilson. Reviewing Wilson’s diaries from the 1930s in The New Yorker, John Updike wrote, “‘Nigger’ seems to be Wilson’s natural way of referring to black people (even ‘coon’ occurs), though as the decade wears on, and he has visited the shacks of Kentucky and the slums of Chicago, the more respectful term ‘Negro’ gradually takes over.”

Looking more closely at Wilson’s work in The New Republic, what we see is less an evolution than a split-mindedness. In a July 1931 article on the Southern Agrarians, Wilson offered a credulous acceptance of neo-Confederate mythology, arguing that “even the master who worked his slaves to death or flogged them to death had perhaps a certain moral advantage over the capitalist manufacturer or speculator. ... To this day, the relations in the South between the landowning gentry and the Negroes are more intimate and, in a sense, more human than the relations between the mill-owner and the workers in the factory.” Remarkably, one month after this whitewashing of slavery, Wilson wrote a masterful summary of the Scottsboro case, based on first-hand reporting, which not only made the miscarriage of justice clear, but also portrayed with great nuance the political and class divisions in the black community that led to a rift in legal tactics.

Wilson would return to neo-Confederate mythmaking in his 1962 book Patriotic Gore, so it’s not quite true to say he progressed on race. Rather he worked in two modes: abstractly as a race theorist (where he wrote nonsense) and concretely as a reporter during the Depression (where he wrote much of value). The discipline of factual journalism, applied to subjects often neglected by the mainstream press, made The New Republic an invaluable repository of black history. At the same time, when these same writers tried to be more speculative, they often fell victim to condescension if not outright, folklore-tinged fantasy.

Fortunately, the magazine also provided a forum where black writers, such as Hubert Harrison, Walter F. White, and Wallace Thurman, could tackle debates in their community. (Alas, black women were scarce, if not non-existent, as contributors to The New Republic, although books by black women were reviewed.) In 1923, while reviewing an inept play by a white writer who mangled African American dialect, Harrison, a black socialist, wrote, “If the fox may be forgiven a word of comment on the hunt, I might even say ‘Bosh!’” Whether it was Du Bois’s prophetic linkage in 1921 of civil rights with anti-imperialist struggles in Africa, or Eric Walrond’s 1922 account of looking for work in New York and getting cold dismissals, a small but vital group of black writers brought sensibilities and perspectives which couldn’t be found elsewhere.

One could argue that between the late ’30s and the mid-’70s, The New Republic was one of the best magazines outside the black press in its coverage of the rise of the civil rights movement. Thomas Sancton, Sr., managing editor from 1942–1943, was a particularly radical advocate, holding FDR’s feet to the fire for his compromises with the Jim Crow South, and doing brave reporting on the Detroit race riots of 1943. Some of the best work from this period is enshrined in the Library of America’s two-volume Reporting Civil Rights, including Lucille B. Milner’s “Jim Crow in the Army” (1944) and Andrew Kopkind’s “Selma” (1965).

After the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act the following year, the country’s conversation about race turned to more ambiguous debates over busing, affirmative action, and overcoming economic hurdles. The owner who would oversee that new era was Martin Peretz.

Peretz would be a neoliberal owner of a liberal magazine, one who took the title editor in chief for himself while nurturing the careers of a cadre of editors in his charge. The magazine became a bully pulpit for Peretz’s political beliefs, but staff members were given free rein to disagree with him in private and public. “I have a problem with some of the needlessly vicious things about Arabs that we publish,” said Michael Kinsley in an interview during his tenure as editor. Peretz’s passion for Israel could occasionally be matched with an unflattering view of Arabs. In a 1982 interview with Haaretz, he urged the Palestinians “be turned into just another crushed nation, like the Kurds or the Afghans.” In a March 1990 essay, he argued the Lebanese “fight simply because they live. And the culture from which they come scarcely thinks this is odd.”

Peretz didn’t reserve his vitriol for Arabs. In 2009, he described Mexico as “a Latin society with all of its characteristic deficiencies: congenital corruption, authoritarian government, anarchic politics, near-tropical work habits, stifling social mores, Catholic dogma with the usual unacknowledged compromises, an anarchic counterculture and increasingly violent modes of conflict.”

Meanwhile, Peretz’s magazine was attributing the problems of black America to Jesse Jackson, Marion Barry, and anonymous welfare mothers, while largely ignoring deindustrialization and mass incarceration. Affirmative action became a regular target; legacy admission of whites to colleges and universities was rarely discussed. Of course, the competing positions on affirmative action deserved an airing. But to attack affirmative action in a magazine with a staff that was almost entirely white and male was to defend not a principle but a troubling status quo.

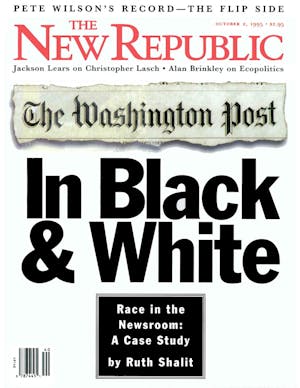

When that point of view permeated a piece of reporting, the results were regrettable. A 1995 piece by Ruth Shalit argued that if The Washington Post hired strictly on merit, it would be an all-white newspaper: “The Post, of course, is in an agonizing position. If editors refuse to adjust their traditional hiring standards, they will end up with a nearly all-white staff. But if they do reach out aggressively to ensure proportionate representation for each relevant minority, they transform not just the complexion but the content of the paper.”

Shalit’s piece made no mention of the fact that the magazine she was writing for had an almost all-white editorial staff. After the piece appeared, roughly half of the 28 Post staffers Shalit interviewed wrote in to say that she had either lied about what they told her or misrepresented them; The New Republic printed only a fraction of these complaints. (The piece was later found to be riddled with inaccuracies, leading James Warren, the Washington bureau chief of the Chicago Tribune to label Shalit a “journalistic Unabomber.”)

Likewise, before his fabrication of articles was revealed in 1998, Stephen Glass penned a 1996 piece about the Washington, D.C. taxi cab industry that seemed to cater to Peretz’s appetite for melodramas illustrating black cultural pathology. The article drew an invidious contrast between hard-working, uncomplaining immigrants who believed in the American dream versus entitled black Americans who spurned honest work (and chased after white women). The piece included imaginary details such as, “Four months ago, a 17-year-old held a gun to Eswan’s head while his girlfriend performed oral sex on the gunman.” Glass also claimed to be in a cab when a young African American man mugged the driver, and celebrated the exploits of a fictional Kae Bang, the “Korean cab-driver- turned-vigilante” who used martial arts to beat up black teenagers who tried to rob his cab. It’s fair to say that Glass’s fabrications in this piece and others did more damage to The New Republic than any event in its history. And it’s hard to accept a piece like the above would have been published in a magazine which wasn’t already inclined toward a pernicious view of African Americans.

One may also ask if a staff dominated by privileged white males might not have benefited from greater diversity, and not just along racial lines. “Marty [Peretz] doesn’t take women seriously for positions of responsibility,” staff writer Henry Fairlie told Esquire magazine in 1985. “He’s really most comfortable with a room full of Harvard males.” In a 1988 article for Vanity Fair, occasional contributor James Wolcott concurred, noting, “The New Republic has a history of shunting women to the sidelines and today injects itself with fresh blood drawn largely from male interns down from Harvard.” When Robert Wright succeeded Michael Kinsley in 1988, he joked he was hired as part of an “affirmative action program” since he went to Princeton, not Harvard.

The magazine’s close ties to Harvard go back to the fledgling days of Croly and Lippmann, both alumni of the Ivy League school. Yet, as Harvard diversified over the decades, The New Republic’s staff did not. Its masthead remained largely demographically unchanged, replicating itself generation after generation. Magazines are as susceptible as any institution to falling into a feedback loop: Just as some universities attract students from the same few families decade after decade, a publication can have a narrow demographic base, drawing its editors from the type of people who grew up reading the magazine. And considering the fact that The New Republic was the gateway for many distinguished careers at publications like The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The Atlantic, the magazine can be seen as not just reflecting the media’s diversity problem, but actively contributing to it.

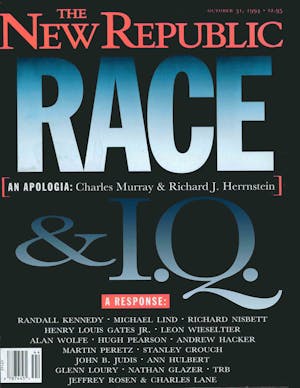

The magazine’s myopia on racial issues was never more apparent than in Peretz’s and editor Andrew Sullivan’s decision in 1994 to excerpt The Bell Curve, a foray into scientific racism in which the authors, Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein, asserted that differences in IQ among blacks and whites were largely genetic and almost impossible to significantly change. The book had not been peer-reviewed, nor were galleys sent to the relevant scientific journals. As The Wall Street Journal reported, The Bell Curve was “swept forward by a strategy that provided book galleys to likely supporters while withholding them from likely critics.”

Staff members at The New Republic vehemently opposed running the excerpt, but Sullivan and Peretz had the final word. A compromise was reached: The excerpt would run along with critiques written by The New Republic contributors, such as Mickey Kaus and John Judis. While the critiques made good points, only one was written by a scientist with the background needed to evaluate the book’s claims. “I’m not a scientist,” literary editor Leon Wieseltier wrote in his contribution. “I know nothing about psychometrics.”

Because most of the critiques were political and philosophic in nature, many readers were left with the false impression that the book had some scientific validity. By the time devastating scientific reviews appeared in places like the Journal of Economic Literature and Intelligence, Genes, and Success: Scientists Respond to The Bell Curve (edited by Bernie Devlin, et. al), the book already enjoyed unmerited prestige, thanks to the imprimatur of The New Republic. The Bell Curve was perhaps the most impactful, and unfortunate, example of the magazine’s embrace of racial mythmaking.

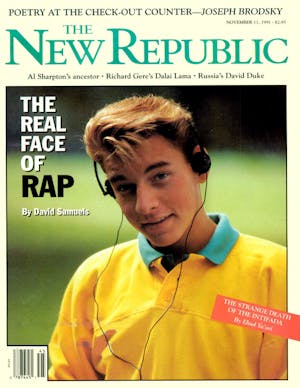

Sometimes, The New Republic’s cluelessness about race was almost comic. A 1991 piece by David Samuels—under the headline “The ‘Black Music’ That Isn’t Either”—assured the magazine’s readers that rap music was neither black nor music, and would be a passing fad. “Whatever its continuing significance in the realm of racial politics, rap’s hour as innovative popular music has come and gone,” Samuels wrote. The issue’s cover showed a white teenager as “The Real Face of Rap.”

Peretz’s New Republic did occasionally publish racially astute pieces, such as Caryl Phillips’s 1996 essay on Trinidadian radical Marxist historian C.L.R. James, and Peter Beinart’s 1997 piece on black-Latino tensions, but such contributions were the exception.

Whatever the problems had been with the early twentieth-century The New Republic, it published a spectrum of black voices, so readers (both black and white) had a sense of how black America thought about things. It published the conservative Washington, the centrist White, the militant Du Bois, and voices more radical than Du Bois himself, such as Du Bois’s Marxist critic Abram L. Harris.

Under Peretz, with very few exceptions, the magazine printed only the more conservative end of black political discourse: Shelby Steele, John McWhorter, Juan Williams, Stanley Crouch, Randall Kennedy, and Glenn Loury.

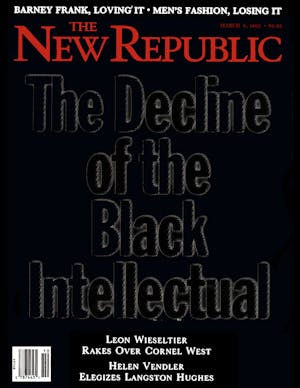

Consider, for example, the black intellectuals who didn’t write for the magazine: Toni Morrison, Michael Eric Dyson, Cornel West, Nell Painter, Robin Kelly, Ismael Reed, and Brent Staples, to name a few. This didn’t stop the magazine from trumpeting “The Decline of the Black Intellectual” on its cover in 1995; the accompanying 5,500-word essay by Wieseltier focused on exactly one intellectual, Cornel West. In fact, black intellectual life was vibrant at the time; it was just absent from The New Republic.

In recent years, under editors Peter Beinart, Richard Just, and Franklin Foer, there was a strong improvement in coverage of race. Dayo Olopade brought a much needed black perspective to her reporting on President Obama’s 2008 run, and in 2014, Alec MacGillis wrote a piece about Scott Walker and the toxic racial politics of Wisconsin. The same year Jason Zengerle wrote incisively about the rollback of civil rights. Rebecca Traister has had wise words about race and the Bill Cosby scandal.

Every magazine is aimed at imaginary readers, an idealized sense of the people leafing through the pages. Perhaps the core problem with Peretz’s New Republic was that the imaginary readers were unquestionably white. It was hard to imagine black readers picking up the magazine, let alone dreaming of writing for it, unless, like The New Republic contributor Walter Williams, they were readers who thought the Confederacy had some merit.

The last century of The New Republic has bestowed a rich legacy of lessons, both positive and negative, on race. At its best moments, the magazine has been a beacon of fact-based reporting and a forum for rich debate over racial issues. At its worst, the magazine has fallen under the sway of racial theorizing and crackpot racial lore. Moving forward, any reformation program should start by honestly acknowledging the past. The range of non-white voices in the magazine needs to expand, not just by having more nonwhite writers, but by having writers who aren’t just talking to an imaginary white audience but are addressing readers who look like the world. The magazine has to avoid the temptation to be an insular insider journal for the elite and recognize that its finest moments are when analytical intelligence is joined with grassroots reporting. The magazine’s well-stocked and complex legacy shouldn’t be jettisoned, but it can be reformed, built on, and made new.