Belle Knox, the enterprising Duke undergraduate who ascended to fame last year after her porn career was discovered by nosy classmates, has decided to direct her notoriety to politics. In an interview with Business Insider, Knox expressed her desire to become a libertarian political activist, having already begun work with libertarian campus groups. Knox evidently identifies failed screenwriter Ayn Rand as a personal hero, and supports the Paul dynasty, citing appreciation for both Ron and son Rand. And she attributed her libertarianism to her conservative religious upbringing.

“I grew up Catholic, so I grew up in a very, very, conservative background and that, I think, really was kind of the impetus for why I wanted to become a libertarian," she said. "I was always being told to cover up my body and I was always being told to wait until marriage to have sex… That really made me become a libertarian and become a feminist.”

Insofar as libertarianism is opposed to almost every feature of Catholic morality, Knox has certainly picked an appropriate politics of rebellion. But Knox, who considers herself “very socially liberal, but … very economically conservative,” may find less agreement among fellow libertarians than she expects. This isn’t because Knox doesn’t have a good sense of what libertarians actually believe; it’s because libertarians themselves do not appear to have a good sense of what libertarianism actually means.

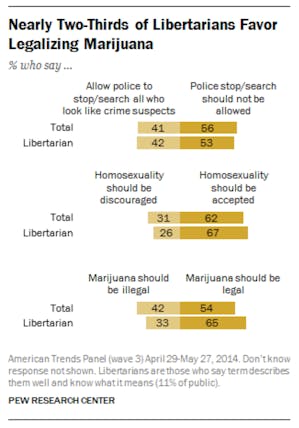

Even Ayn Rand detested libertarians, whom she identified with hippies and considered irrational, ineffectual opponents of true freedom. When it comes to polling libertarians, it certainly appears that they aren’t quite as socially liberal as their nomenclature might suggest. In a Pew survey last year, for example, libertarians polled as plenty supportive of police intervention in citizens’ daily lives, showing slightly greater support for stop-and-frisk policies than the general population:

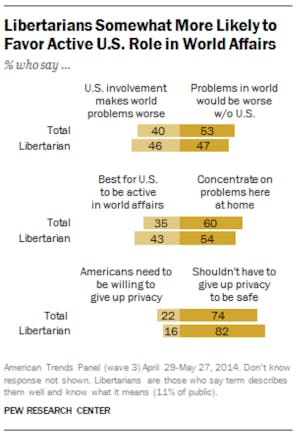

A baffling quarter of libertarians surveyed believe homosexuality should be discouraged, and 59 percent were opposed to same-sex marriage in a survey conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute in 2013. Meanwhile, the inexplicable libertarian appreciation for cops frisking people at will is mirrored by an equally bizarre fondness for U.S. military intervention in global affairs.

All this while supporting privacy, though perhaps only for themselves, and not for those on the receiving end of police shakedowns and U.S. drones. The only thing libertarians really seem to agree with their label on is the subject of poverty, with 57 percent claiming that government aid to poor people does more harm than good, and 56 percent responding that government regulation of business does more harm than good. If Knox sees libertarianism as a direct counterpoint to Catholic teaching, then this point should be of greatest interest to her, as libertarian disinterest in state efforts to care for the poor really is the antithesis of Catholic teaching on moral states. But insofar as Knox cites attorney Gloria Allred as a hero she would like to emulate, she still doesn’t appear to apprehend what libertarianism actually means: While Allred has spent a career fighting against gender discrimination, this also means she has spent a career levying state power to reverse privately made decisions about employment, pay, and so on. Like it or not, this is the regulation of business.

Knox is only 19 years old, so we can hardly fault her for these contradictions. Libertarianism itself has no such excuse. How to explain its adherents' schizophrenia on matters that would, to an observer, seem to have fairly clear-cut libertarian approaches? The problem is that, while libertarians seem to agree that they favor freedom, and appear to be in agreement that freedom is reduced by state intervention, they do not have a positive working definition of what freedom actually is. For Belle Knox, freedom has to do with decriminalized sex work and fair pathways for women in employment—but both of those projects imply a level of proactive government regulation in business. For the jingoistic libertarians polled in the Pew survey, freedom clearly has to do with domestic freedom from criminal activity and threats abroad—but in those cases, some other person or group must be inspected or restrained to achieve such a sense of liberty. Libertarians who oppose government aid to the poor seem to desire freedom from taxes, but have no interest in whether or not the poorest are really free to exercise their rights to human flourishing when they can barely eat.

In other words, libertarianism comes with a love of freedom but no consistent sense of what really constitutes freedom or who it is for. For libertarian politicians and their advocates, the sheer slipperiness of the concepts at hand may be a feature rather than a bug, allowing them to cherry-pick policies they personally prefer and shape malleable definitions around them. But for genuine, invested activists like Knox, the evasiveness of the libertarian message should be a red flag.