Last year didn't go according to plan for Kansas Governor Sam Brownback. First, the state’s revenue collections came up far short of expectations due to huge tax cuts that he pushed through the state legislature in 2012. Those tax cuts, however, didn’t spur strong growth, as the governor projected. Then, as his policies drew national criticism, Brownback found himself in a tight reelection contest, despite Kansas' being a very conservative state.

Brownback survived, winning by less than 4 points. But now he's faced with a gaping hole in the state’s budget, thanks to his tax cuts—and his new proposal to fill that hole will hurt the poorest Kansans and undermine the state’s future.

After the 2013 fiscal year, Kansas was in good shape. It had more than $700 million in a reserve fund, equal to more than 11 percent of its spending that year ($6.1 billion). In fact, state law requires Kansas to keep its balance equal to 7.5 percent of expenses. In total that year, the budget brought in about $200 million more than the state spent.

But then the tax cuts kicked in. Revenue in the 2014 fiscal year came in $333 million below projections—and nearly $700 million below the 2013 levels. Spending fell by around $150 million, but the state still faced a deficit of $329 million. Because the reserve fund was flush with cash, Brownback and his Republican colleagues didn’t have to making drastic cuts or hike taxes to close the shortfall. They just subtracted it from the reserve fund, leaving it with just $380 million remaining.

In 2012, Brownback called his plan a “real live experiment” for conservative economic policy. So when Kansas announced those revenue numbers last summer, the national media took notice. At the New York Times, Josh Barro reported on the flaws in Kansas’s tax plan; it tried to exempt small-businesses from taxation, but in doing so, it also opened up a loophole that could allow many Kansans to avoid paying taxes. Remaining confident in the plan, Brownback's administration attributed the fiscal 2014 revenue shortfall to changes in federal tax policy that incentivized people to switch their capital gains income into 2012. If that was the case, then the revenue hole was just a temporary problem, one that would disappear in the 2015 fiscal year.

Seven months into the 2015 fiscal year, though, that problem looks anything but temporary. In November, the Kansas Legislative Research Department, which provides nonpartisan reports to Kansas legislators, as the Congressional Budget Office does for Congress, lowered its revenue estimates by $205 million, to $5.8 billon. Kansas is projected to spend $6.4 billion in this fiscal year. Even with $380 million in the reserve fund, the budget still has a $279 million gap. But it’s even worse than that. In January, Kansas’s revenue came in $42 million below projections, although the governor’s office says that $22 million of that is due to Kansans filing their taxes and receiving refunds earlier than expected. Altogether, new projections estimate the 2015 shortfall at $344 million. And since Kansas, like most state governments, by law can’t run a deficit, it has to fill that gap before the fiscal year ends on June 30.

On Tuesday, Brownback signed legislation that would balance the budget by diverting money from other funds, particularly one for highway projects, to the general fund. It would also reduce contributions to pensions for teachers and government workers, pushing those costs into the future. It’s a deeply irresponsible budget that hides the costs of the tax cuts with short-term patches. But this is just the beginning: Kansas faces a projected $600 million budget shortfall in the 2016 fiscal year—and now there is no money in the reserve fund to cover any of it.

Covering that gap will not be easy. In late January, Brownback sent the legislature a proposed budget to address the problem. He wants to cut more than $100 million from school finances and $50 million from Medicaid. He would increase cigarette taxes by $0.79, which would bring in $81 million. Another $27 million would come from increasing taxes on liquor. He’d even bring in more income tax revenue by closing certain tax deductions. And he wants to transfer another $200 million from other funds to the general fund.

The budget's massive cuts to education might even be unconstitutional. In December, a state court ruled that the state was not spending enough money on K-12 education to fulfill “the educational interests of the state.” Brownback is appealing the decision to the Kansas Supreme Court. But if the Court rules against him, the state will be forced to increase K-12 funding by nearly $500 million—all while keeping the reserve fund at a zero balance. To fulfill its 7.5 percent threshold would require another half billion dollars.

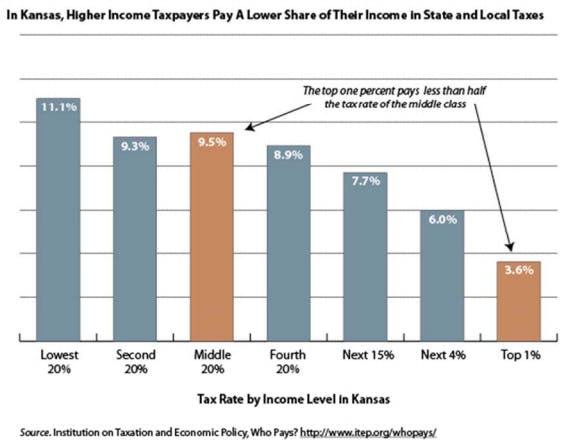

There’s a much better way for Kansas to fulfill its constitutional duties and avoid these yearly budget shortfalls: give up on its failed tax cuts and raise revenue. And that revenue should come from the richest Kansans. Between 1979 and 2012, the top 1 percent of Kansans has nearly doubled its share of income, from 9.8 percent to 18.6 percent. In fact, the top 1 percent pay just 3.6 percent of their income in state and local taxes, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. The middle 20 percent of earners pay 9.5 percent.

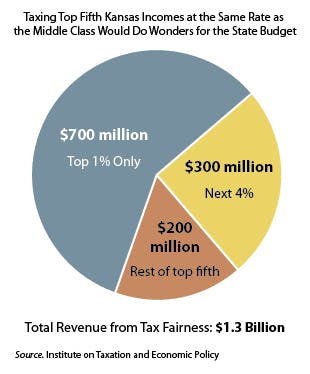

Kansas could raise a lot of money this way. A new report from the Keystone Research Center and Good Jobs First (both are left-leaning) finds that taxing the top 1 percent at the same rate as the middle class would bring in $724 million in additional revenue. Taxing the top 20 percent of Kansans at the same rate as the middle class would bring in $1.3 billion.

Of course, that would require a major tax increase on the richest Kansans. A tax hike of that size could have negative economic implications on the state. But Kansas doesn’t face a $1.3 billion shortfall. The state could also use a combination of tax increases on the rich and spending cuts elsewhere to balance the budget. In other words, the legislature doesn’t have to equalize the tax rates between the middle class and the rich to balance its budget. It just has to make them more equal.

Regardless of how Brownback handles this problem, it isn’t going away. He can only divert money from other funds and delay pension contributions for so long. At some point, he’ll have to admit that his tax cuts have left a gargantuan hole in the budget and this “real live experiment” is a real live failure.

This article originally stated, citing a report from the Keystone Research Group and Good Jobs First, that taxing the top 1 percent and the top 20 percent of Kansans at the same rate as the middle 20 percent would bring in additional revenue of $938 million and $2 billion, respectively. The Keystone Research Group has since issued a correction. The actual figures are $724 million and $1.3 billion.