Seventy-five years ago, in his autobiographical volume Hitler and I (1940), the one-time Nazi party member and later renegade, Otto Strasser, offered up a frank reminiscence about Hitler’s infamous book, Mein Kampf. Strasser was dining with several high-ranking Nazi officials at the 1927 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg when he was asked if he had ever read Hitler’s notorious treatise.

Strasser replied:

“I admitted having quoted some significant passages from it without bothering my head about the context. This caused general amusement, and it was agreed that the first person who joined us who had read Mein Kampf should pay the bill for us all. Gregor [Otto’s brother and a leading party member]’s answer was a resounding ‘No,’ Goebbels shook his head guiltily, Goering burst into loud laughter, and Count Reventlow excused himself on the ground that he had had no time. Nobody had read Mein Kampf, so everybody had to pay his own bill.”

While historians have long debated how many Germans actually read Mein Kampf during the Third Reich, today a different question has arisen: Will anyone in Germany read it once it can be legally published there in early 2016? And what might be the impact on a digital generation for whom the Führer is a distant memory or internet meme?

Later this year, the official copyright for Mein Kampf expires—70 years after the demise of its author. Since 1945, the Bavarian State (which owns the copyright) has refused to allow anyone to publish the volume. But in expectation of the copyright’s expiration (and in the hope of getting a jump on neo-Nazis who may try to publish their own slanted versions of the text) the esteemed Munich and Berlin-based Institute for Contemporary History decided some years ago to publish its own, critically annotated version. The move has generated some opposition, with some arguing against the release of any new version; “Can you annotate the Devil?” one critic asks.

The question is whether anyone will have the strength to lift, let alone read, the new edition. The volume will be hefty, numbering more than 2,000 pages—the result of nearly 5,000 annotations supplied by scholars. These annotations will critically engage Hitler’s ideologically rooted claims in Mein Kampf, the goal being to prevent gullible readers from accepting any of them at face value.

Who will read the new edition of Mein Kampf?

Neo-Nazis and other right-wing extremists will surely shy away from this new volume. But what about younger Germans who may simply be curious about the book? To be sure, they—like all German readers—have been able to access used and online versions of Mein Kampf for some time (even though selling or distributing the book is against German law) thanks to Internet vendors. But if they haven’t found their way to a version of the book by now, will they be tempted to look at the forthcoming edition?

Perhaps some will. But the likelihood is that the weighty tome will appeal to very few who belong to the millennial generation. Younger Germans, like their peers worldwide, have grown up reading brief Twitter feeds and Facebook posts. When browsing the web, their attention spans, if estimates are to be believed, run to less than thirty seconds per website. Moreover, they have been exposed to countless examples of the “Hitler Meme,” in the form of irreverent images that spoof the former Führer, in the form of satirical videos on YouTube, websites like Cats That Look Like Hitler, and online games like Six Degrees of Hitler. Today’s youth culture, in short, is accustomed to superficially mocking, rather than deeply engaging, with Hitler and his legacy.

For this reason, those who fearfully imagine adverse political repercussions arising from the re-issuing of Mein Kampf probably needn’t worry. Indeed, in important ways, the book runs counter the essential dynamics of present-day web culture.

My new book, Hi Hitler! highlights my research into the increasingly common commercialization and normalization of the Nazi past. I argue that a new internet rule has recently come into being, which I term the “Law of Ironic Hitlerization.” It asserts that the likelihood of an image getting attention on the web increases as soon as a Hitler moustache, swastika, or any other Nazi iconography is applied to it. For those brave enough, doing a brief image search on Google will turn up endless images of otherwise blameless characters—Hello Kitty, Colonel Sanders, the Teletubbies—who have fallen victim to this dynamic.

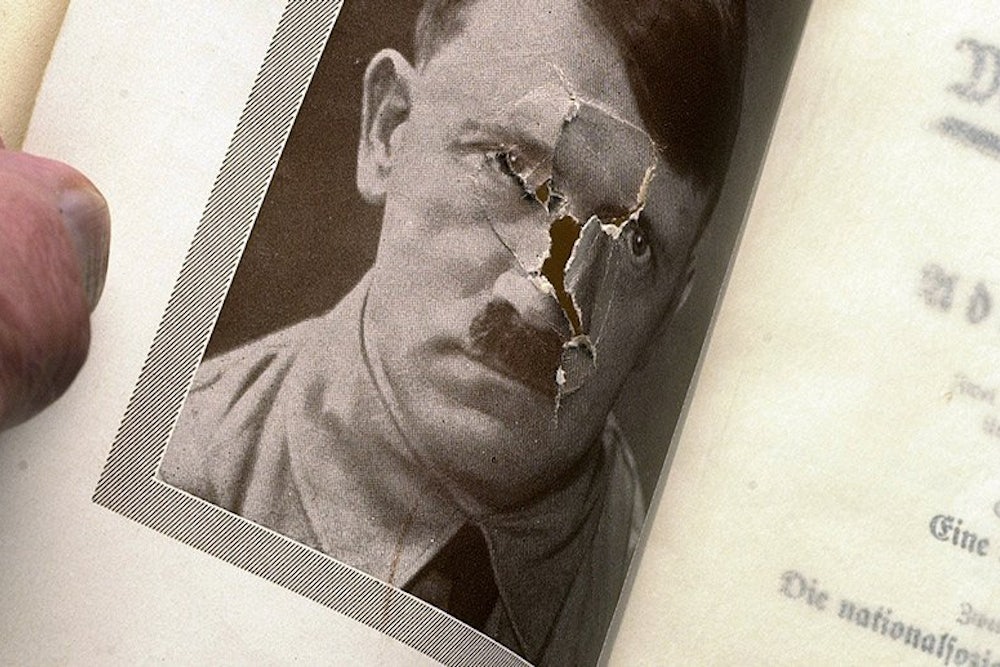

In all likelihood, however, Mein Kampf will resist the “Law of Ironic Hitlerization.” Unless intrepid web users can devise a way to “Hitlerize”—that is, to affix Nazi iconography to—Mein Kampf’s textual passages and footnotes, the reappearance of the book, for many readers, will be akin to stumbling upon a fossil.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.