The Obama Administration has just made it official: The U.S. hopes to cut greenhouse gas pollution by 26-28 percent by 2025. The White House submitted its plan to the United Nations just before the informal Tuesday deadline, in a symbolic step meant to propel other countries to make similar commitments. So far, 34 countries—including Russia, Mexico, Switzerland, Norway, and some members of the European Union—have submitted formal pledges. At the end of the year, an international climate change conference will collect more than 100 pledges in an accord or treaty that will hopefully put the world on track to tackle global warming.

The international agreement in Paris faces immense challenges, however. Not everyone is so willing to tackle climate change around the world, and mixed messages from politicians at home are confusing to the international community. On the same day the administration submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell was out with his own message to world leaders. "Considering that two-thirds of the U.S. federal government hasn't even signed off on the Clean Power Plan and 13 states have already pledged to fight it, our international partners should proceed with caution before entering into a binding, unattainable deal," McConnell warned in an emailed statement.

A successful Paris deal rests in part on how well the White House can assure the rest of the world that the Obama administration can overcome political (conservative) intransigence. Congress won't work with Obama, so he's making it clear that he himself can put the country on track to meet its commitments. In the Paris pledge, the White House emphasized executive action as the key to achieving 26-28 percent pollution reductions.

On a call with reporters, White House senior advisor Brian Deese maintained that the target is both “ambitious and achievable within existing legal authority.” The five-page plan notes three times that the target can be achieved under laws already passed by Congress, like the Clean Air Act, the Energy Policy Act, and the Energy Independence and Security Act. The INDC also discusses what America has already done: power plant regulation, better fuel economy standards for vehicles, executive actions lowering methane from landfills and public lands, and emission reduction standards for other potent greenhouse gasses, like hydroflurocarbons.

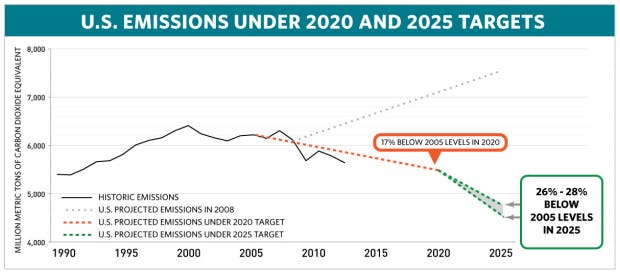

The emphasis on executive action is new, says Peter Ogden, a former White House climate official during the last major climate conference in Copenhagen. In 2009, the administration pledged to cut pollution 17 percent by 2020. If the U.S. succeeds in matching its Copenhagen goal, it will have only 9-11 percent more to go before 2025, with roughly 2-3 percent cuts per year.

Obama's regulations on power plant pollution—the U.S.'s largest single source of carbon—are crucial to the Paris plan's success. Yet the future of the regulations on new and existing power plants is still in question. Even so, it's important for the administration to convince the world the U.S. can be trusted. “The undoing of the kind of regulations that’s being put in place is tough to do,” Todd Stern, the U.S.’s top climate negotiator, said. He tells countries that ask about the "solidity of U.S. action” that Obama's regulations will stand the court and political battles. “The kind of regulation being put in place is not easily undone,” he said.

The next occupant of the White House matters, too. “Administrations build on but reflect a durable commitment to these goals in the future," Deese said. But he didn't explain what the next administration would have to accomplish.

Elliot Diringer, executive vice president of Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, suggested that the current administration has to make progress in cutting emissions before Obama exits. "We have to see how far they are able to get while the president is in office," he said. And Diringer notes that policy isn't the only option available. "The target sends a strong signal to the marketplace about the need to decarbonize and that will drive investment, efficiency, and clean energy beyond the policy mandates," he continued.

Republicans in Congress are fully aware the president intends to act alone and they are predictably unhappy about it. “The Obama administration’s national energy policy is practically a national windmill policy—which is like going to war in sailboats when nuclear warships are available," Senator Lamar Alexander said in an emailed statement, urging Obama to work with Congress. He’s been saying the same thing since at least 2008—even though Congress hasn't given any indication it's ready to act on climate change.

This article has been updated.