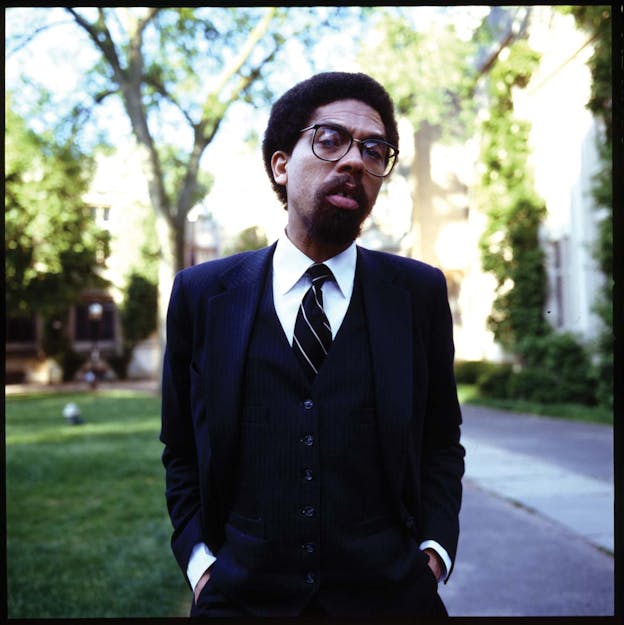

Cornel West, at his peak, was “the most exciting black American scholar ever,” wrote professor Michael Eric Dyson in this 2015 reappraisal of his onetime friend. He was hardly alone in that opinion. West, a theologian and philosopher, had become an intellectual force in the 1980s for “effortlessly surfing the broad waves of Western thought, defending the notion of black humanity while laying siege to white sectarianism,” and then became an unlikely academic celebrity in the 1990s for his rhetorical style: “an extemporaneous exploration of ideas that features the improvised flourishes and tonal colors of a jazz musician and the rhythmic shifts and sonic manipulations of a gospel preacher.”

But West’s petty, unrelenting rage at President Obama forced Dyson to face an uncomfortable truth: West had been in intellectual decline for many years. “In his callous disregard for plural visions of truth, West, like the prophet Elijah, retreats into a deluded and self-important belief in his singular and exclusive rightness,” Dyson wrote, adding, “Now he lumbers into his future, punch-drunk from too many fights unwisely undertaken, facing a cruel reality: His greatest opponent isn’t Obama.… It is the ghost of a self that spits at him from his own mirror.” This bombshell argument raised some hackles, to say the least—prompting Jamil Smith, who co-edited the essay, to write an impassioned answer to the question, “Why, considering this magazine’s history of a white gaze and a white audience, did it appear in The New Republic?”

—Ryan Kearney, executive editor, The New Republic

“Nor hell a fury like a woman scorned” is the best-known line from William Congreve’s The Mourning Bride. But I’m concerned with the phrase preceding it, which captures wrath in more universal terms: “Heaven has no rage like love to hatred turned.” Even an angry Almighty can’t compete with mortals whose love turns to hate.

Cornel West’s rage against President Barack Obama evokes that kind of venom. He has accused Obama of political minstrelsy, calling him a “Rockefeller Republican in blackface”; taunted him as a “brown-faced Clinton”; and derided him as a “neoliberal opportunist.” In 2011, West and I were both speakers at a black newspaper conference in Chicago. During a private conversation, West asked how I escaped being dubbed an “Obama hater” when I was just as critical of the president as he was. I shared my three-part formula for discussing Obama before black audiences: Start with love for the man and pride in his epic achievement; focus on the unprecedented acrimony he faces as the nation’s first black executive; and target his missteps and failures. No matter how vehemently I disagree with Obama, I respect him as a man wrestling with an incredibly difficult opportunity to shape history. West looked into my eyes, sighed, and said: “Well, I guess that’s the difference between me and you. I don’t respect the brother at all.”

West’s animus is longstanding, and only intermittently broken by bouts of calculated love. In February 2007, West lambasted Obama’s decision to announce his bid for the presidency in Illinois, instead of at journalist Tavis Smiley’s State of the Black Union meeting in Virginia, calling it proof that the nascent candidate wasn’t concerned about black people. “Coming out there is not fundamentally about us. It’s about somebody else. [Obama’s] got large numbers of white brothers and sisters who have fears and anxieties, and he’s got to speak to them in such a way that he holds us at arm’s length.” It is hard to know which is more astonishing: West faulting Obama for starting his White House run in the state where he’d been elected to the U.S. Senate—or the breathtaking insularity of equating Smiley’s conference with black America.

Despite West’s disapproval of Obama, he eventually embraced the political phenom, crossing the country as a surrogate and touting his Oval Office bona fides. The two publicly embraced at a 2007 Apollo Theater fundraiser in Harlem during which West christened Obama “my brother... companion and comrade.” Obama praised West as “a genius, a public intellectual, a preacher, an oracle,” and “a loving person.”

Obama welcomed West’s support because he is a juggernaut of the academy and an intellectual icon among the black masses. If black American scholars are like prizefighters, then West is not the greatest ever; that title belongs to W.E.B. Du Bois. Not the most powerful ever; that’s Henry Louis Gates Jr. Not the most influential; that would include Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison, Black History Week founder Carter G. Woodson, historian John Hope Franklin, feminist bell hooks, Afrocentricity pioneer Molefi Kete Asante—and undoubtedly William Julius Wilson, whose sociological research has profoundly shaped racial debate and the public policies of at least two presidents. West may be a heavyweight champ of controversy, but he has competition as the pound-for-pound greatest: sociologists Oliver Cox, E. Franklin Frazier, and Lawrence D. Bobo; historians Robin D.G. Kelley, Nell Irvin Painter, and David Levering Lewis; political scientists Cedric Robinson and Manning Marable; art historian Richard J. Powell; legal theorists Kimberlé Crenshaw and Randall Kennedy; cultural critic Tricia Rose; and the literary scholars Hortense Spillers and Farah Jasmine Griffin—all are worthy contenders.

Yet West is, in my estimation, the most exciting black American scholar ever. At his peak, each new idea topped the last with greater vitality. His fluency in a remarkable range of disciplines spilled effortlessly from his pen, and the public performance of his massive erudition inspired many of his students to try to follow suit, from religious studies scholars Obery Hendricks and Eddie Glaude Jr. to cultural critics Imani Perry and Dwight McBride. West may not be Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis, Jack Johnson, Jersey Joe Walcott, or Sugar Ray Robinson. He’s more Mike Tyson, a prodigiously gifted champion who rose to the throne early and tore through opponents with startling menace and ferocity. His reign was brutal, his punch devastating, his impact staggering.

It was that sense of scholarly excitement that drew me to West after I read his first book, Prophesy Deliverance!, in 1982. The book validated the intellectual passion I’d courted in my youth, never leaving me as I navigated some challenging circumstances. I had been a promising student from a Detroit ghetto who won a scholarship to a prestigious boarding school outside of town on the condition that I repeat the eleventh grade. I confronted racism head on for the first time at that new school, and it rocked me: I was expelled during my second year for poor performance. I returned to the inner city and the prospect of collecting my diploma at night school. I got married and became a teenage father, one who worked in an auto-supply factory and hustled odd jobs after high school. I didn’t start college until the fall of 1979, one month before my twenty-first birthday. That same year, I divorced my son’s mother after moving South to attend the historically black Knoxville College. My father died two years later, and I made do for a spell with the only material inheritance he could pass on: a Chevy station wagon that had once served as the work vehicle for our Dyson & Sons grass-cutting, sod-laying, and odd jobs enterprise. Over the next few years, I served as pastor of three different churches in Tennessee while completing my degree at Carson-Newman College, 20 miles northeast of Knoxville, where I transferred in 1981 to get a firmer footing in my study of philosophy.

When West’s book was published, my phone service at home had been shut off because I had no money to pay the bill. There was a pay telephone outside the laundromat where I washed my clothes, and one day, instead of doing the laundry, I spent my last $5 calling West at his Union Theological Seminary office in New York City. I rhapsodized about his philosophical acumen and cutting-edge theories of race for a while, and West let on that he had heard about me from a mutual friend and encouraged me to stay in touch. I took him at his word and soon scrounged up the money to drive the 600 miles from Tennessee to see him deliver a series of talks at Kalamazoo College.

West had not yet freed himself from reading his lectures to develop the rhetorical style for which he is justly celebrated: an extemporaneous exploration of ideas that features the improvised flourishes and tonal colors of a jazz musician and the rhythmic shifts and sonic manipulations of a gospel preacher. Yet even then West mesmerized, effortlessly surfing the broad waves of Western thought, defending the notion of black humanity while laying siege to white sectarianism—proving by his own impossibly literate performance that white superiority was a lie, at least as long as his gap-toothed mouth spit out esoteric knowledge.

West and I became dear friends. I admired his penetrating intellect and he nurtured my deepening commitment to a life of the mind. West wrote a letter of recommendation on my behalf when I applied to graduate school in 1984 and helped me to land at his alma mater Princeton, where he had been the first black student ever to earn a doctorate in philosophy, and where I became the second black student to earn a doctorate in religion. West had a huge crush on the R&B singer Anita Baker, and I got us tickets to see her perform in New Jersey. After a brief backstage introduction to the singer I had finagled, West relived his high school track glory and sprinted up the street in glee.

As a graduate student, I arranged for West to lecture at Princeton in the late ’80s, before he was an academic superstar, and I can still remember how he inventively grappled with the decline of European domination, the rise of American hegemony, and the decolonization of Third World countries, even as he spoke of the pervasive influence of black culture in the broader life of the nation, citing Matthew Arnold, T.S. Eliot, Lionel Trilling, and Frantz Fanon as major witnesses to the trends he outlined. I had observed literary scholar Houston Baker dazzle another Princeton audience with a dynamic and dramatic lecture, but West topped that performance with the sheer breadth of his inquiry and the erudite ad-libs to his written presentation.

West’s early work was a marvel of rigor and imagination. He rode the beast of philosophy with linguistic panache as he snagged deep concepts and big thinkers in his theoretical lasso and then herded thousands of stalking students into Ivy League classrooms packed to the rafters. In Prophesy Deliverance!, West invited Foucault to sing the “insurrection of subjugated knowledges” in the black revolutionary choir. The American Evasion of Philosophy (1989) ingeniously pitched American pragmatism as a multiracial conversation that included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Du Bois, and Richard Rorty. And in Keeping Faith (1993), West gathered a slew of seminal essays on subjects like social theory and the philosophy of religion—baptizing poststructuralist thought in American waters while translating the insight of its biggest European stars with analytical verve.

At the age of 39, West catapulted to fame after struggling financially and became, deservedly, a far richer man with the publication of his best-known work, 1993’s Race Matters. It isn’t a scholarly book, per se, although its pages carry the weight of his formidable intellect as he traces the cultural dynamics of race with exquisite and uncharacteristic—for the time—lucidity. (Dense jargon was at its zenith in the postmodernist academy of the 1990s.) Race Matters changed how we speak of black identity in the United States. It gave our country a golden pun for matters of race that mattered more than they should and brought West the sort of celebrity that is intoxicating and distracting. West garnered glowing profiles in Newsweek and Time—in the same week—and explored his ideas on radio with Terry Gross and on television with Bill Moyers and Bill Maher. There was a certain satisfaction in West’s rise: One of the smartest men of his generation also became one of its most popular.

The intellectual landscape had shifted dramatically beneath West’s feet by the time Obama went after the presidency. The Internet and social media ushered in new voices on the nation’s most vexing problems and made room for fresh thinking on race and identity. Even as the pace of West’s published scholarship slowed, he remained a powerful cultural presence. If West’s most notable book argued that race mattered, his celebrity and iconic status meant that his endorsement also mattered.

West remained allied with Obama until he took the White House and, in football parlance, faked left and ran right. “[Obama] posed as a progressive and turned out to be counterfeit,” West complained in an interview with Salon. “He acted as if he was ... concerned about the issues of serious injustice and inequality, and it turned out that he’s just another neoliberal centrist with a smile and with a nice rhetorical flair.” It’s worth noting that the president’s actions were in keeping with the demands of his profession: Like most recent Democratic politicians, Obama nodded in a progressive direction while campaigning but toed a more centrist line when it came time to govern. What distinguishes West is that he assailed Obama’s insufficient leftism and proclaimed it a racial betrayal. “I would rather have a white president fundamentally dedicated to eradicating poverty and enhancing the plight of working people than a black president tied to Wall Street and drones,” he told The Guardian.

Long before their ideological schism, however, West believed himself personally betrayed by Obama because of his (supposed) disinterest after the election. It is a sad truth that most politicians are serial rhetorical lovers and promiscuous ideological mates, leaving behind scores of briefly valued surrogates and supporters. West should have understood that Obama had had similar trysts with many others. But West felt spurned and was embittered.

This is where Congreve’s insight on love decomposed to rage comes crashing in. West has repeatedly declared that he did 65 engagements for the presidential campaign in 2008, and was offended when the president didn’t provide tickets to the inauguration. (Obama later told me in the White House that West left several voice messages, including prayers, from a blocked number with no instructions of where to return the call, a routine with which I was all too familiar.) In a 2011 interview with Chris Hedges on Truthdig that appeared under the headline “The Obama Deception: Why Cornel West Went Ballistic,” West recalled his indignation during the Inauguration, when he arrived at his Washington hotel with his mother, and she noted that the bellman had a ticket to the event but not her son. “I couldn’t get a ticket for my mother and my brother,” West said. “We drive into the hotel and the guy who picks up my bags from the hotel has a ticket to the inauguration. My mom says, ‘That’s something that this dear brother can get a ticket and you can’t get one, honey, all the work you did for him from Iowa.’” Thus the left-wing critic found it unjust that the workingman and not the professor had a ticket to the inauguration. Only in a world where bankers and other fat cats greedily gobble rewards meant for everyday citizens would such a reversal appear unfair. J.P. Morgan might have been mad; Karl Marx would have been ecstatic.

This moment for West followed a pronounced and decades-long scholarly decline, something that did not escape the notice of other academics and intellectuals, none more notably than Lawrence Summers, the former president of Harvard, who clashed publicly with West. (West departed Harvard for Princeton in 2002.) Summers had reprimanded West for his varied side projects, everything from advising Reverend Al Sharpton’s failed presidential bid to his vanity musical ventures. I couldn’t endorse these criticisms, but I knew Summers was right when he pointed to West’s diminished scholarly output. It is not only that West’s preoccupations with Obama’s perceived failures distracted him, though that is true; more accurate would be to say that the last several years revealed West’s paucity of serious and fresh intellectual work, a trend far longer in the making. West is still a Man of Ideas, but those ideas today are a vain and unimaginative repackaging of his earlier hits. He hasn’t published without aid of a co-writer a single scholarly book since Keeping Faith, which appeared in 1993, the same year as Race Matters. West has repeatedly tried to recapture the glory of that slim classic by imitating the 1960s-era rhythm and blues singers he loves so much: Make another song that sounds just like the one that topped the charts. In 2004, West published Democracy Matters, an obvious recycling of both the title and themes of his work a decade earlier. It was his biggest seller since Race Matters.

Even a cursory survey of West’s recent work captures the noticeable diminishment of his intellectual force. Hope on a Tightrope (2008) is mostly a collection of West-ian wisdom spoken and then transcribed. The cover features West standing at a blackboard with the words “What Would West Say?” chalked again and again, like an after school punishment, a haunting hubris suggesting a parallel to “What Would Jesus Do?” His memoir Brother West (2009) is an embarrassing farrago of scholarly aspiration and breathless self-congratulation—West, for instance, deems his co-authored book The War Against Parents (1998) a “seminal text”; praises Race Matters as “the right book at the right time”; and brags that Democracy Matters sold over 100,000 copies, landed at No. 5 on TheNew York Times bestseller list, and “continues to influence many.” None of this competes with the description on West’s website of his first spoken word album, Sketches of My Culture, which claimed at the time of its release that in “all modesty, this project constitutes a watershed moment in musical history.”

Brother West was co-written with David Ritz, a writer best known for album liner notes and ghostwriting entertainers’ biographies—a sure sign of West’s dramatic plummet from his perch as a world-class intellectual. It’s one thing for Ray Charles to turn to Ritz; another thing entirely for a top-shelf scholar to concede that he can’t write for himself, or is too busy to do so. It is akin to Du Bois hiring Truman Capote to fashion his autobiography. The journalist David Masciotra called The Rich and the Rest of Us (2012), which was also co-authored, this time by Tavis Smiley, “a cover version of a hit performed better by other singers—Barbara Ehrenreich, Joseph Stiglitz, and William Julius Wilson, to name a few.” West’s latest, Black Prophetic Fire, published last year, is another talk book, this one edited by Christa Buschendorf, a German scholar who interviewed West. Last October, Masciotra reviewed Fire for The Daily Beast, and called it “a strange and disappointing culmination of [West’s] metamorphosis from philosopher to celebrity,” one that is in keeping with “his pattern of not solely authoring any books in the past ten years.” If you’re counting: That’s two talk books and two co-authored ones across a decade—not quite up to the high scholarly standard West set for himself long ago.

In Brother West, West admitted that he is “more a natural reader than natural writer,” adding that “writing requires a concerted effort and forced discipline,” but that he reads “as easily as I breathe.” I can say with certainty, as a college professor for the last quarter century, that most of my students feel the same way. What’s more, West’s off-the-cuff riffs and rants, spoken into a microphone and later transcribed to page, lack the discipline of the written word. West’s rhetorical genius is undeniable, but there are limits on what speaking can do for someone trying to wrestle angels or battle demons to the page. This is no biased preference for the written word over the spoken; I am far from a champion of a Eurocentric paradigm of literacy. This is about scholar versus talker. Improvisational speaking bears its wonders: the emergence on the spot of turns of thought and pathways of insight one hadn’t planned, and the rapturous discovery, in front of a live audience, of meanings that usually lie buried beneath the rubble of formal restrictions and literary conventions. Yet West’s inability to write is hugely confining. For scholars, there is a depth that can only be tapped through the rigorous reworking of the same sentences until the meaning comes clean—or as clean as one can make it.

The ecstasies of the spoken word, when scholarship is at stake, leave the deep reader and the long listener hungry for more. Writing is an often-painful task that can feel like the death of one’s past. Equally discomfiting is seeing one’s present commitments to truths crumble once one begins to tap away at the keyboard or scar the page with ink. Writing demands a different sort of apprenticeship to ideas than does speaking. It beckons one to revisit over an extended, or at least delayed, period the same material and to revise what one thinks. Revision is reading again and again what one writes so that one can think again and again about what one wants to say and in turn determine if better and deeper things can be said.

West admires the Socratic process of questioning ideas and practices in fruitful dialogue, and while that may elicit thoughts he yearned to express anyhow, he’s at the mercy of his interlocutors. Thus when West inveighs, stampedes, and kvetches, he gets on a roll that might be amplified in conversation but arrested in print. It’s not a matter of skillful editing, either, so that the verbal repetition and set pieces that orators depend on get clipped and swept aside with the redactor’s broom. It’s the conceptual framework that suffers in translating what’s spoken to what’s written, since writing is about contrived naturalness: rigging the system of meaning to turn out the way you want, and making it look normal and inevitable in the process.

An essential tenet of West’s arguments, and the centerpiece of his public identity, is his belief about prophets, and more important, his claim to be one. West’s follow-up to Prophesy Deliverance! was Prophetic Fragments, a 1988 collection of essays, lectures, and speeches. Two more volumes followed in 1993: Prophetic Thought in Postmodern Times and Prophetic Reflections. “I am a prophetic Christian freedom fighter,” West wrote in one essay, adding in his memoir, “I see my role as ... someone who feels both a Socratic and prophetic calling.”

Prophets in the Judeo-Christian tradition draw on divine inspiration to speak God’s words on earth. They are called by God to advocate for the poor and vulnerable while decrying unrighteousness and battling injustice. Among black Americans, prophecy is often rooted in religious stories of overcoming oppression while influencing the moral vision of social activists. Black prophets are highly esteemed because they symbolize black resistance to white supremacy, stoke insurgence against the suppression of our freedom, inspire combat against social and political oppression, and risk their lives in the service of their people and the nation’s ideals. They remind us of the full measure of God’s love for the weak and unprotected, especially in an era when prophecy has been co-opted, turned into a bland cultural commodity, and marketed as the basis for enterprising exploits of major corporations or for political gain.

We see this phenomenon each year during the birthday celebration for Martin Luther King Jr., one of the greatest figures in both black and U.S. history, and someone who is revered as a prophet. Fast food corporations trumpet King’s message of togetherness and yet often fail to pay a living wage to their workers, even as conservative politicians pay homage to King’s memory while implementing voter ID laws that imperil the franchise for millions of black citizens. The same culture that killed King now seeks to kill contemporary expressions of his prophetic itinerary, by portraying today’s activists, such as those found in #BlackLivesMatter and the movement to end police brutality, as the moral opposites of his social vision and ’60s-era nonviolent protest. The argument over who and what is prophetic has rarely been more heated in black culture than it is now.

The model of the charismatic black male leader has come in for deserved drubbing since it overlooks the contributions of women and children that often went unheralded in the civil rights movement and earlier black freedom struggles. Queer activists sparked the #BlackLivesMatter movement, underscoring the unacknowledged sacrifice of black folk who are confined to the closets and corners of black existence. Even those who enjoy a direct relationship to King and to Malcolm X haven’t escaped scrutiny. Louis Farrakhan is faulted (and praised) for his distance from Malcolm’s racial politics, and Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton have been pilloried for lacking King’s gravitas and grace. The truth of those assessments is not as important as the value of the comparison: It holds would-be prophets to account for standards of achievement both noble and nostalgic, real and imagined.

Despite the profusion of prophecy in his texts and talks, West has never bothered to tell us in rich detail what makes a person a prophet. He doesn’t offer a theory of prophets so much as announce their virtues and functions while grieving over their lost art and practice. In Black Prophetic Fire, West offers a sweeping assessment of contemporary black life: “Black people once put a premium on serving the community, lifting others, and finding joy in empowering others,” he wrote. “Black people once had a strong prophetic tradition of lifting every voice.” Today, however, “Black people have succumbed to individualistic projects in pursuit of wealth, health, and status. ... [They] engage in the petty practice of chasing dollars.”

West offers no empirical proof for these claims; like so much of his recent work there are assertions without sustained and compelling arguments, and certainly no polls or studies that prove the increase in black materialism, or individualism, or the decline in black prophetic beliefs and behavior. West’s failure to carefully chart the history and ethical arc of prophecy leads him to wild overstatement. To paraphrase Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous definition of pornography, West may not seek to define a prophet, but he knows one when he sees one, and quite often, they sound just like him. This limp understanding of prophecy plays to his advantage because he can bless or dismiss prophets without answering how we determine who prophets are, who gets to say so, how they are different from social critics, to whom they answer, if they have standing in religious communities, or if God calls them.

West has never given us detailed comparative analyses of prophets in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, or Zoroastrianism, nor has he distinguished between major and minor prophets. He hasn’t explored the differences between social and political prophecy; examined the fruitful connections between the biblical gift of prophecy and its cultural determinants; or linked his understanding of prophecy to secular expressions of the prophetic urge found in New Left radicalism, for example, which led to Jack Newfield’s notable analysis of the movement in A Prophetic Minority. (To be fair, Newfield didn’t spend a great deal of time exploring prophecy either; but then he didn’t fancy himself a prophet like West, nor did he viciously lambast those who fall short of his expectations or standards.)

What makes West a prophet? Is it his willingness to call out corporate elites and assail the purveyors of injustice and inequality? The actor Russell Brand does that in his book Revolution. Is he a prophet? Is it West’s self-identification with the poor? Tupac Shakur had that on lock. Should we deem him a prophet? Is it West’s self-styled resistance to police brutality, evidenced by his occasional willingness to get arrested in highly staged and camera-ready gestures of civil disobedience, such as in Ferguson last fall? West sees King as a prophet, but Jackson and Sharpton, who have also courted arrest in public fashion, are “ontologically addicted to the camera,” according to West. King used cameras to gain attention for the movement, a fact West fails to mention in his attacks on Jackson, “the head house Negro on the Clinton plantation,” and Sharpton, “the head house Negro on the Obama plantation.”

The hypocrisy in such claims is acute: West likewise hungers for the studio, and conspicuously so. There he is on CNN, extolling his prophetic pedigree. There he is on MSNBC, discussing his arrest in Ferguson while footage of the event rolls. There he is in the recording booth making not spoken word or hip-hop, but a grimly earnest sonic hybrid of speech and music, and saying, “If I can reach one young person with a message embedded in a sound that stirs his or her soul, then I have not labored in vain.” There he is in The Matrix sequels, doing something he’s become tragicomically good at—playing an unintentional caricature of his identity.

West most closely identifies with a black prophetic tradition that has deep roots in the church. But ordained ministers, and especially pastors, must give account to the congregations or denominations that offer them institutional support and the legitimacy to prophesize. They may face severe consequences—including excommunication, censorship, being defrocked, or even expelled from their parishes—for their acts. The words and prophetic actions of these brave souls impact their ministerial standing and their vocation. West faces no such penalty for his pretense to Christian prophecy.

West might argue that not being ordained leaves him free to act on his prophetic instincts and even disagree with the church on social matters. Thus he avoids the negative consequences of ordination while remaining spiritually anchored. That’s fine if you’re a run-of-the-mill Christian, but there is, and should be, a higher standard for prophets. True prophets embrace religious authority and bravely stand up to it in the name of a higher power. The effort to escape responsibility should sound an alarm for those who hold West’s views about how prophets should behave. One need not be Martin Luther King to qualify as a prophet. But when you claim to be a prophet, you are expected, as the classic gospel song goes, to live the life you sing about in your song.

As an ordained minister and professor, I know the difference between the professorate and the pastorate, between prophets and scholars. When I utter progressive beliefs about equal rights for women or queer folk as a professor, I am sometimes lauded. When I was a church pastor—not a prophet, something I have never claimed to be—the same sermon that garnered praise from progressive scholars earned me scorn from church officials and members and even cost me a pastorate when I tried to put my beliefs into action and ordain women as deacons.

As a freelancing, itinerant, nonordained, self-anointed prophet, West has only to answer to himself. That may symbolize a grand resistance to institutional authority, but it’s also a failure to acknowledge the institutional responsibilities that religious prophets bear. Most ministers are clerics attending to the needs of the local parish. Only a select few are cut from prophetic cloth. Yet nearly all the religious figures we recognize as prophets—Adam Clayton Powell Jr., King, Jackson, Sharpton—were ordained as ministers. Powell and King were pastors of local churches as well. To be sure, there are prophets who are not ministers or religious figures—especially women whose path to the ministry has been blocked by sexist theologies—but most of them have ties to organizations or institutions that hold them accountable.

West has a measure of responsibility as a professor, but he enjoys far greater freedom than most ministers or prophets. Professors have a lot of flexibility in teaching classes, advising students, writing books, and speaking their minds without worrying that a deacon board will censor them or trustees will boot them out. Prophets, as a rule, don’t have tenure. West gets the benefits of the association with prophecy while bearing none of its burdens. By refusing to take up the cross he urges prophetic Christians to carry, West is preaching courage while seeking to avoid reprisal or suffering. Playing it safe means that West doesn’t qualify for the prophetic role he espouses.

West’s lack of understanding of the prophetic tradition is perhaps most evident in his criticism of Sharpton and Jackson. He berates them for their appetite for access to power, their desire for insider status. Even if we concede for the moment that this is true, it isn’t a failure of their prophecy but of West’s ability to distinguish between kinds of prophets. In his 1995 book, The Preacher King, Duke Divinity School Professor Richard Lischer noted that in ancient Israel, the central prophet moved within the power structure, reminding the people of their covenant with God and also consulting kings on military matters and issues of national significance. Peripheral prophets were outsiders who embraced the poor, criticized the monarchy, and opposed war.

West ignores these variations, which results in an idealized, and deeply flawed, portrait of King as a peripheral prophet who was only useful when he hugged the margin. But that, Lischer argued, is a distorted rendering of King’s prophetic profile:

As a central prophet, Martin Luther King had been deeply involved with the Johnson administration’s efforts to pass civil rights legislation. Beginning already in the Eisenhower administration and increasing steadily throughout the turbulent Kennedy years, he had been regularly consulted on matters of interest to the Negro in America. After the March on Washington, Kennedy had scrambled to align himself with King’s beautifully articulated ideals. In some of Lyndon Johnson’s early civil rights speeches, King was gratified to hear echoes of his own ideas. No black leader had ever enjoyed comparable access to the Oval Office and the power it represented.

King moved from central to peripheral prophet in his last few years with an emphasis on economic justice and antiwar activism—views he grew into as he wrestled with his conscience, his staff, and the folk to whom he was accountable. But West’s insistence that only peripheral prophets are genuine and powerful is undercut by the legislation King helped to pass as a central prophet: the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. King was arguably more beneficial to the folk he loved when he swayed power with his influence and vision. When West begrudges Sharpton his closeness to Obama, he ignores the fact that King had similar access.

Sharpton and Jackson moved in the opposite prophetic direction of King. While King kissed the periphery with courageous vigor after enjoying his role as a central prophet, Jackson, and especially Sharpton, started on the periphery before coming into their own on the inside. Jackson’s transition was smoothed by the gulf left by King’s assassination, and while forging alliances with other outsiders on the black left, he easily adapted to the role of the inside-outsider who identified with the downcast while making his way to the heart of the Democratic Party.

Sharpton, lacking the leeway that derives from a leader’s violent death, had instead to kill his persona; the rabble-rousing and inflammatory style of his early days is gone. West remains an elite academic and can hardly be said to have ever been a true outsider, given his position in the academic elite and the upper reaches of the economy, but he hungers to be seen as rebellious. In truth, West is a scold, a curmudgeonly and bitter critic who has grown long in the tooth but sharp in the tongue when lashing one-time colleagues and allies.

Leon Wieseltier famously derided West’s work as “almost completely worthless” in these pages 20 years ago. And although I strongly disagree with Wieseltier’s views of West’s early works, it would be fitting for West to downsize his ambition and accept his role as a public intellectual, social gadfly, or merely a paid pest. There’s nobility in such roles, and one need not dress up one’s intellectual vocation as a prophetic one. West may draw on prophetic insight; he may look up to prophets on the front lines; and he may even employ prophetic vocabularies of social dissent. But none of that makes him a prophet. One of West’s heroes, Malcolm X, said that just because a cat has kittens in the oven doesn’t make them biscuits. That’s what philosophers call a category mistake.

If West’s harangues against Obama are not the words of a prophet, then how do we account for his extravagant excoriations? They might be explained with a bit of the moral psychology West likes to apply to the president. West said in 2011 that “my dear brother Barack Obama has a certain fear of free black men,” because as a biracial child growing up in a white world, “he’s always had to fear being a white man with black skin.” West said that when Obama “meets an independent black brother, it is frightening.” Yet Obama wasn’t too frightened to confront West. According to Jonathan Alter’s 2013 book, The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies, at the 2010 National Urban League convention, Obama barked at West, “I’m not progressive? What kind of shit is this?” Other foul words were uttered, West added, and Obama “cussed me out.” A photo of the exchange exists: West frozen like a dear brother in the headlights as he smiled broadly and stood speechless.

The irony is that, as highly charged as his criticism has become, West is, in some ways, not that different from Obama. The president has long wished to be the grand architect of bipartisanship, the conciliator of left and right, the bridge between conservatives and liberals. West used to fancy himself a similar figure; at least he did when he was riding high on best-seller lists as a progressive icon. West sought to account for the suffering of black America by steering between the arguments of conservative behaviorists and liberal structuralists. He thought it was important to acknowledge self-inflicted injuries as well as dehumanizing forces. As Stephen Steinberg, a sociologist at Queens College, has argued, West set himself up as “the voice of reason and moderation between liberals and conservatives,” as the “mediator between ideological extremes.” Obama has similarly argued that black folk must cultivate moral excellence at home and in the community even as he admits the government must help fight black suffering.

West’s prescription for what ails black folk—and a big part of Obama’s plan, too—involves a personal and behavioral dimension beyond social or political change. For West, the cure is a politics of conversion fueled by a strong love ethic. “Nihilism is not overcome by arguments or analyses; it is tamed by love and care,” West wrote in Race Matters. “Any disease of the soul must be conquered by a turning of one’s soul. This turning is done through one’s own affirmation of one’s worth—an affirmation fueled by the concern of others.” Obama believes the blessed should care for the unfortunate, a hallmark of his My Brother’s Keeper initiative. West and Obama both advocate intervention for our most vulnerable citizens, but while West focuses on combating market forces that “edge out nonmarket values—love, care, service to others—handed down by preceding generations,” Obama, as Alter contends, is more practical, offering Pell grants; stimulus money that saved the jobs of hundreds of thousands of black state and local workers; the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced the disparity of sentences for powdered and crack cocaine; the extension of the Earned Income Tax Credit, which kept millions of working poor blacks from sliding into poverty; and the extension of unemployment insurance and food stamps, which helped millions of blacks.

The odd thing is that Obama talks right—chiding personal irresponsibility in a way that presumes the pathology of many black families and neighborhoods—but veers left in his public policy. West, on the other hand, talks left but thinks right in his notion of nihilism and the factors that might reduce its peril. In Race Matters, West argued that the spiritual malady of “nihilism” is the greatest threat to black America—not racism, not class inequality, not material hardship or poverty or hyperincarceration. Steinberg rightly argues that it “takes hairsplitting distinctions, that do not bear close scrutiny, to maintain that West’s view of nihilism is different from the conservative view of ghetto culture as deeply pathological, and as the chief source of the problems that beset African Americans.” Steinberg says that despite “frequent caveats, West has succeeded in shifting the focus of blame onto the black community. The affliction is theirs—something we shall call ‘nihilism.’” West did as much to slam the poor with his stylish, postmodern update of ghetto pathology and blame-the-victim reasoning as any conservative thinker. He gave the notion ideological cover because it got a sexy upgrade from a prominent leftist. As much as West berates Obama’s neglect of the poor, his own writing brought them harsher visibility than they deserved.

The conservative underpinnings of West’s views on nihilism make his confrontations with progressives like Melissa Harris-Perry, a Wake Forest professor and MSNBC host whom he helped to recruit to Princeton in 2006, curious to say the least. The conflict with her stemmed from an essay Harris-Perry wrote in 2008 for The Root accusing Tavis Smiley of throwing “a temper tantrum” because Obama had declined to attend his State of the Black Union conference in New Orleans that year. In the article, Harris-Perry also jabbed at West for levying the same criticism at Obama for skipping the event in 2007. Smiley, West, and their supporters, she wrote, had created a “false, racial litmus test” for Obama, one that he failed simply by not showing up.

Harris-Perry again attacked West in 2011 in The Nation, decrying his “self-aggrandizing, victimology sermon deceptively wrapped in the discourse of prophetic witness.” West, she wrote, “offers thin criticism of President Obama and stunning insight into the delicate ego of the self-appointed black leadership class that has been largely supplanted in recent years.” West fired back in a 2012 Diverse magazine interview, saying, “I have a love for the sister, but she is a liar, and I hate lying.” West called Harris-Perry “the momentary darling of liberals,” but he “pray[ed] for her because she’s in over her head. She’s a fake and fraud.” Harris-Perry told Diverse that she left Princeton for Tulane in 2011 after some members of the African American studies department blocked her promotion to full professor.

If West is no prophet but instead a dynamic and once-indispensable social critic, neither is his nastiness the echo of divine disfavor from on high. In a 2014 interview on HuffPost Live, Morehouse College Professor Marc Lamont Hill challenged West about his attacks on his fellow black progressives. West compared himself to biblical prophets Jeremiah and Amos, contending there is “a certain intensity to prophetic language that hits deep and seems to be unfair, but is coming from a place of such righteous indignation.” Not content to be in league with mere prophets, West compared himself with Christ, with those who disagreed with him cast in the role of the Lord’s unprincipled opponents. “If we could hear what Jesus was saying when he ran out the money changers in the temple, it was not polite discourse.”

If this isn’t the height of self-righteousness, it is the depth of delusion and exegetical corruption—isolating and then interpreting a text to sanctify his scurrilous views. But West’s broadsides lack a crucial element. Lischer argued that late in his career King, too, “began to give full vent to his rage.” But unlike West, King’s “was the holy rage of the prophetic tradition, and not the resentment or vengefulness of his nationalist critics, to which he lent his voice. His prophetic forebears, as it were, taught him how to get mad, what themes to press, and what language to use.”

In his callous disregard for plural visions of truth, West, like the prophet Elijah, retreats into a deluded and self-important belief in his singular and exclusive rightness. But God reminded Elijah that his prophetic exclamations were wrong. He instructed him to rest and recognize that he wasn’t the only one left who believed in God or bore witness to the truth. But these words mean nothing to West, who, after all, isn’t a prophet. He cannot retreat, and he relentlessly declares his humility to shield himself from the prophet’s duty of pitiless self-inventory.

West and I participated in several State of the Black Union meetings, as well as a 2010 roundtable in Chicago to address the black agenda. I expressed love for Obama and criticized him for not always loving us back, arguing that Obama the president is Pharaoh, not Moses: a politician, not a liberator. Throughout his presidency I have offered what I consider principled support and sustained criticism of Obama, a posture that didn’t mirror West’s black-or-white views—nor satisfy the Obama administration’s expectation of unqualified support.

In The Center Holds, Alter described a meeting Obama held with prominent black figures in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, during which radio host Tom Joyner “began to mix it up with the author Michael Eric Dyson, who wanted the administration to target its efforts more on particular black needs.” Alter wrote, “Obama jumped in to say he had no problem with Dyson or anyone else disagreeing with him about how to help the needy,” but that he got upset with “critics who ‘question my blackness and my commitment to blacks.’” I said nothing to the president that day that I hadn’t said many times over the years.

If West’s accusation that some progressives are Obama apologists rings false, his finding fault in those who crave access is downright laughable. That’s because West shamelessly flaunts his proximity to the rich and famous and takes pride in knowing there are powerful people who love and admire him. It’s all there in West’s memoir, Brother West. “It was the summer of 1988, and we were all gathered around the grand piano at Carly Simon’s home on Martha’s Vineyard,” he writes. The “we” includes Simon, West, and the opera singer Kathleen Battle, his girlfriend at the time. West got to meet other famous people because of Battle. “Roberta Flack invited us to her apartment at the Dakota,” and Battle “introduced me to two fabulous maestros: the inimitable James Levine ... and the famous conductor Christoph von Dohnányi.” Then there’s the time in 1998 that Warren Beatty phoned West and asked if he could take a look at a film he’d just made. “When the film was over, Warren turned to me and asked the $64,000 question, ‘Should I release it?’ I didn’t hesitate. ‘Absolutely,’ I said. ‘It’s a fascinating critique of capitalism and market-driven politics. I think ... [it] needs to be seen.’” Thus we have West to thank for Beatty’s political comedy, Bulworth. After giving the actor-director the green light, West said he, Beatty, and their filmmates for the night, Norman Mailer and his wife, “talked our heads off till three in the morning.”

And then there’s music mogul Sean “Diddy” Combs, whom West met after the star’s attorney—“my dear friend Johnnie Cochran Jr.”—called him and said, “Corn, Sean is in deep trouble,” asking West to come to court with Combs for moral support during his trial for gun possession and bribery. There’s the time he met the hip-hop artist Snoop Dogg on a flight from Chicago to Houston. “I spotted Snoop Dogg and, just like that, announced publicly, ‘Lyrical genius on the plane!’” Or the time he hung out with Prince, who “had graciously invited me to his Bel Air mansion.” West said he was approached at Prince’s home “by a beautiful Latina, who was overflowing with intellectual passion,” and at “evening’s end, I told the sweet lady that it was a delight” as “Salma Hayek went her way and I went mine.”

There are literally pages and pages of illustrious name-dropping in Brother West, a book that owes its subtitle, Living and Loving Out Loud, to another boldface name—Bob Dylan. West was in an airport when Dylan’s drummer approached him and said that the legendary artist loved and respected West. The drummer relayed something Dylan said about the professor: “‘Cornel West,’ said Dylan, ‘is a man who lives his life out loud.’”

Perhaps West despises the access of Sharpton and others to Obama because, unlike them, he has heroically resisted such impulses and invitations. But he couldn’t hush his enthusiasm when another president, Bill Clinton, invited him to the White House after the publication of Race Matters. West said Clinton brought him to the Oval Office, “eager to engage in serious intellectual conversation about culture and politics.” Writing of Clinton, West says:

The brother was absolutely brilliant and I was having a ball. When I looked at my watch, though, I saw it was far into the middle of the night. We had been at it for hours. I realized I had an early morning flight back to New Jersey to teach at Princeton and needed just a little nod of sleep. But he was as fresh as ever. I remember thinking to myself—Does this brother have a job?—when I realized—He’s the president of the United States! I did leave, but only after another hour of conversation.

West offers himself a benefit that he refuses to extend to others: He can go to the White House without becoming a presidential apologist or losing his prophetic cool. He can spend an evening with the president, the first of many such evenings, without selling his soul. West can delight in meeting Clinton, with the sudden burst of recognition that he’s in the presence of the president of the United States!—the italicized enthusiasm is all his! West’s hypocrisy in the matter is radiant;it shines through his belief that only he can resist the siren call of presidential access and retain his “black card” and his three-piece prophet’s robe of honor.

West’s attacks on me were a bleak forfeiture of 30 years of friendship; it was the repudiation of fond collegiality and intellectual companionship, of political camaraderie and joined social struggle. I was a mentee and, according to West, who was kind enough to write a blurb for one of my books, “a rare kind of genius with organic links to our beloved street brothers and sisters.” But I had somehow undergone a transformation in West’s mind: I was an Obama stooge who had forsaken the poor. In November 2012, West, friend and mentor, one of the three men whose name is on my Princeton doctoral dissertation, let me have it in the national media.

It was during an appearance with Tavis Smiley on Democracy Now, shortly after Obama’s reelection. “I love Brother Mike Dyson,” West said. “But we’re living in a society where everybody is up for sale. Everything is up for sale. And he and Brother Sharpton and Sister Melissa and others, they have sold their souls for a mess of Obama pottage. And we invite them back to the black prophetic tradition after Obama leaves. But at the moment, they want insider access, and they want to tell those kinds of lies. They want to turn their back to poor and working people. And it’s a sad thing to see them as apologists for the Obama administration in that way, given the kind of critical background that all of them have had at some point.”

West was just warming up. After a fiftieth anniversary celebration of the 1963 March on Washington on the National Mall, a celebration Sharpton led and at which I spoke, West argued that Martin Luther King Jr. “would’ve been turning over in his grave” at Sharpton’s “coronation” as the “bona fide house negro of the Obama plantation,” supported by “the Michael Dysons and others who’ve really prostituted themselves intellectually in a very, very ugly and vicious way.” And recently, while promoting Black Prophetic Fire, West argued “the Sharptons, the Melissa Harris-Perrys, and the Michael Eric Dysons ... end up being these cheerleaders and bootlickers for the President, and I think it’s a disgrace when it comes to the black prophetic tradition of Malcolm and Martin.”

West’s aggressions brought me great sorrow. In his anger toward me I was forced, for the first time, to entertain seriously the wild accusations levied against him: that he was consumed with jealousy of Obama, that he simply couldn’t abide the rise of a figure who eclipsed most other black personalities for the time being and who, for many, even competed with King for recognition as the “greatest black man in American history.” I still don’t buy those theories, but I do think West’s deep loathing of Obama draws on some profoundly personal energy that is ultimately irrational—it’s a species of antipathy that no political difference could ever explain. It is sad to think that West aimed at me because my criticism failed to comport with his shrill and manic dispute with the president; our lost friendship is the collateral damage of his war on Obama.

West has sacrificed friendships and cut ties with former comrades because he insists that only outright denunciation of Obama will do. It is a colossal loss for such a gifted man to surrender to unheroic truculence: If a mind is a terrible thing to waste, then the loss of a brilliant black mind is more terrible, more wasteful. At precisely the moment when we could use the old West’s formidable analytical skills to grapple with the myriad polarities that glut the political horizon, the new West, already in the clutches of a fateful denouement, has instead sought the empty solace of emotional catharsis.

If West was once Tyson in his glory, he is Tyson, too, in his infamy. Once great, once dominant, once feared, he is now a faint echo of himself. Like Iron Mike, West is given to biting our ears with personal attacks rather than bending our minds with fresh and powerful scholarship. Like Tyson, he is given to making cameos—in West’s case, appearing as himself in scripted social unrest, or playing a prophet on television in the latest protest. He has squandered his intellectual gift in exchange for celebrity. He’s grown flabby with disinterest in the work needed to stay aloft: the readiness to read, think, and recast thought in the crucible of written words.

West’s memoir offers a poignant and honest accounting of his relationship with women, and by extension, his relationship with Obama, who was, for a time, the object of West’s profound political affection:

Because I’ve never been an advocate of psychotherapy as a path to self- understanding. . . . I’ve avoided such therapy because I worry about how it might exacerbate narcissistic tendencies. . . . I’m not sure I know myself well enough to share my whole self with others. This, in part, might explain my volatile relationships with women. One might argue that because I don’t know myself, the more time I spend with a woman, the more various parts of myself emerge—parts that are, in fact, foreign to me. In short, my whole self surfaces, and it is precisely my whole self that strikes me as a stranger. To maintain a long-term and long-lasting bond with a woman may require the kind of soul-sharing or self-sharing that’s beyond my capability.

West’s fears of his narcissistic tendencies seem to have come true in his fight with President Obama. Hedges also used the language of the jilted lover in describing West, noting that he “nurses, like many others who placed their faith in Obama, the anguish of the deceived, manipulated, and betrayed.” West admitted to Hedges in their interview that he went “ballistic” about Obama because he had been “thoroughly misled”; or, put differently, he was crushed that Obama had ideologically cheated on him.

West’s narcissism in this matter is not exemplified by his sense of being jilted but in the way he has personalized his grief. And the longer West has nursed his resentment, the more he has revealed parts of himself that even he may not understand or be able to explain, since political disappointment in a politician’s behavior rarely provokes such torrents of passion, such protracted, dastardly, and sadly, such self-destructive hate. The volatility that West said roils his personal relations may also mar his political ones. Now he lumbers into his future, punch-drunk from too many fights unwisely undertaken, facing a cruel reality: His greatest opponent isn’t Obama, Sharpton, Harris-Perry, or me. It is the ghost of a self that spits at him from his own mirror.