Every morning, Kim Casipong strolls past barbed wire, six dogs, and a watchman in order to get to her job in a pink apartment building decorated with ornate stonework in Lapu-Lapu City. The building towers above the slums surrounding it—houses made of scrap wood with muddy goat pens in place of yards. She is a pretty, milk-skinned, 17-year-old girl who loves the movie Frozen and whose favorite pastime is singing karaoke. She is on her way to do her part in bringing down Facebook.

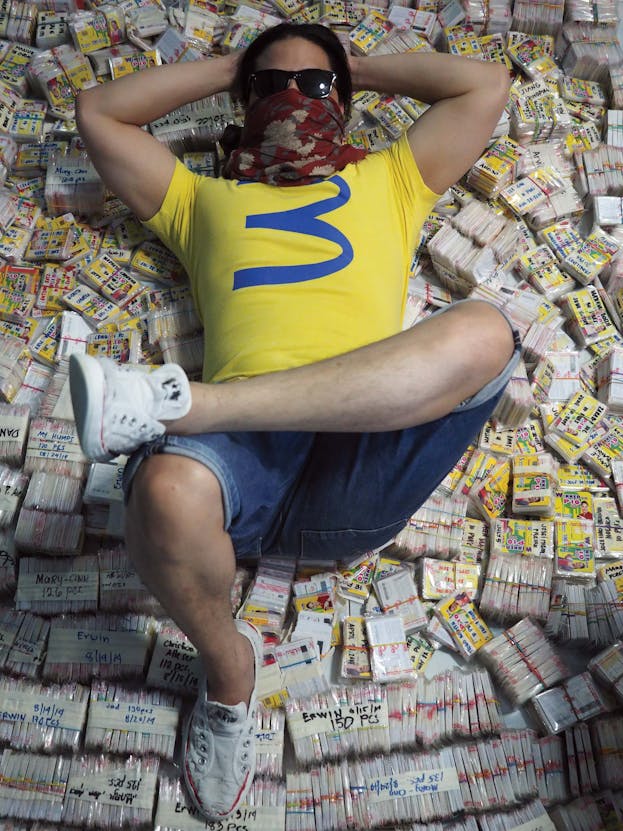

Casipong huffs to the third floor of the apartment building, opens a door decorated with a crucifix, and greets her co-workers. The curtains are drawn, and the artificial moonlight of computer screens illuminates the room. Eight workers sit in two rows, their tools arranged on their desks: a computer, a minaret of cell phone SIM cards, and an old cell phone. Tens of thousands of additional SIM cards are taped into bricks and stored under chairs, on top of computers, and in old instant noodle boxes around the room.

Richard Braggs, Casipong’s boss, sits at a desk positioned behind his employees, occasionally glancing up from his double monitor to survey their screens. Even in the gloom, he wears Ray-Ban sunglasses to shield his eyes from the glare of his computer. (“Richard Braggs” is the alias he uses for business purposes; he uses a number of pseudonyms for various online activities.)

Casipong inserts earbuds, queues up dance music—Paramore and Avicii—and checks her client’s instructions. Their specifications are often quite pointed. A São Paulo gym might request 75 female Brazilian fitness fanatics, or a Castro-district bar might want 1,000 gay men living in San Francisco. Her current order is the most common: Facebook profiles of beautiful American women between the ages of 20 and 30. Once they’ve received the accounts, the client will probably use them to sell Facebook likes to customers looking for an illicit social media boost.

Most of the accounts Casipong creates are sold to these digital middlemen—“click farms” as they have come to be known. Just as fast as Silicon Valley conjures something valuable from digital ephemera, click farms seek ways to create counterfeits. Google “buy Facebook likes” and you’ll see how easy it is to purchase black-market influence on the Internet: 1,000 Facebook likes for $29.99; 1,000 Twitter followers for $12; or any other type of fake social media credential, from YouTube views to Pinterest followers to SoundCloud plays. Social media is now the engine of the Internet, but that engine is running on some pretty suspect fuel.

Casipong plays her role in hijacking the currencies of social media—Facebook likes, Twitter followers—by performing the same routine over and over again. She starts by entering the client’s specifications into the website Fake Name Generator, which returns a sociologically realistic identity: Ashley Nivens, 21, from Nashville, Tennessee, now a student at New York University who works part time at American Apparel. (“Ashley Nivens” is a composite based on Casipong’s standard procedures, not the name of an actual person or account.) She then creates an email account. The email address forms the foundation of Ashley Nivens’s Facebook account, which is fleshed out with a profile picture from a photo library that Braggs’s workers have compiled by scraping dating sites. The whole time, a proxy server makes it seem as though she is accessing the Internet from Manhattan, and software disables the cookies that Facebook uses to track suspicious activity.

Next, she inserts a SIM card into a Nokia cell phone, a pre-touch-screen antique that’s been used so much the digits on its keypad have worn away. Once the phone is live, she types its number into Nivens’s Facebook profile and waits for a verification code to arrive via text message. She enters the code into Facebook and—voilà!—Ashley Nivens is, according to Facebook’s security algorithms, a real person. The whole process takes about three minutes.

Casipong sometimes wonders what happens to profiles like these once she turns them over to the clients. In fact, her whole job seems strange to her and the purpose of all these accounts somewhat mysterious. Still, she forgets this for long stretches of time: She’s young, she can do an almost perfect karaoke rendition of Mariah Carey’s “We Belong Together,” and she dreams of finishing college at the University of Cebu City after she’s saved enough money from working for Braggs. Once she earns a degree in Web design, she’ll join the Philippine diaspora and find a job in Australia, New Zealand, or the United States. And during weekends, maybe she can lead a life similar to Nivens’s.

When Casipong stands up a little after 6 p.m., a nightshift worker is waiting to take her chair.

Once, if you wanted to make money scamming people on the Internet, you used email. For two years, Braggs made his living spamming half a billion email addresses, hawking blueprints for a mythical perpetual energy machine or e-books that explained the secret to winning the lottery. Filipinos even invented a term for this kind of work, “onlining,” and, for about a decade, email spamming was a semi-honorable career path in Cebu City, the metropolitan area that encompasses Lapu-Lapu City and is one of the foremost business-outsource processing centers in the world. (Ring JPMorgan Chase or Microsoft customer support, and there’s a good chance you’ll be connected to a Filipino in Cebu City whose excellent English is part of the legacy of the American colonization of the Philippines.) Successful “onliners” became the nouveau riche of Cebu City. A notorious set of six brothers formed a spamming cooperative and built a row of mansions amid the slums. They threw all-night parties with roving guitarists serenading scores of guests, while they drank beer and devoured lechón, Philippine whole-roasted pig.

But between 2010 and 2012, teams of Internet security researchers and law enforcement officials dismantled several spambot networks across the world. These efforts, combined with the improved defenses of email hosts, effectively disabled many onliners in Cebu City. They had to look for new ways to make money.

Social media’s takeover of the Internet has been swift and dramatic. From 2005 to 2012, the percentage of Internet-using, American adults on a social media platform mushroomed from 8 to 70 percent. In 2005, Facebook had 5.5 million users; at the end of 2014, Facebook claimed 1.39 billion active monthly users—about one for every five people in the world and a little less than half of all people with Internet access.

In 2009, Facebook introduced the “like” button, which quickly became a way for people to celebrate an engagement or the birth of a baby, but also for brands to get people to endorse their products. Companies loved social media for the ostensible humanity it lent them; and sales leads that came through social media, studies showed, had a much higher chance of converting into actual purchases. Google and Bing’s algorithms take social media into account, so large followings could also improve a company’s position in search-engine rankings, where appearing even one slot higher can mean significant additional revenue. Researchers have also found that having lots of followers attracts even more followers, continually amplifying a company’s or individual’s reach. And while the impact of traditional advertising is difficult to quantify, social media counters are much more transparent.

Celebrities—and more minor personalities, like bloggers trying to get endorsement deals—have increasingly found their value measured in Facebook fans and Twitter followers, the payments they receive proportionate to their social media clout. Khloé Kardashian reportedly earns around $13,000 every time she tweets things like, “Want to know how Old Navy makes your butt look scary good?” to her 13.6 million followers. Politicians desire large followings for obvious reasons. Even ordinary people have discovered perks to having an extensive social media presence. Some employers, for instance, now require social media savvy for jobs in marketing, PR, or tech. All these logical incentives aside, the imperatives are not always rational. A growing body of research has begun to unpack the envy and insecurity that social media can generate—the pernicious sense that your friends are gaining Twitter followers much faster than you.

To help companies, celebrities, and everyday people boost their social media standing, onliners set up Internet stores—“click farms”—where customers can buy social media influence. Click farms can be found across the globe, but are most commonly based in the developing world. They exist in India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and the Philippines, and may also exist in Eastern Europe, Mexico, and Iraq. A small number of click farms employ manual labor, a dozen or so people who manipulate Facebook accounts individually to create the likes that they sell. But most click farms are run by smaller teams that manage software to give digital life to accounts like Ashley Nivens. What Braggs runs is actually referred to as an “account farm”—he makes the accounts and software that click farms use.

In terms of their professionalism, click farms range widely. Some maintain promotional newsletters, subscription packages, and 24/7 customer service. One of the more polished, We Sell Likes, was founded by a former Silicon Valley SEO professional. Others are much less formal: a freelancer sitting in front of his computer all day and selling the services of hundreds of social media accounts through websites like SEO Clerks. Last November, The New York Times reported that teenagers were licensing Twitter click-farm software to supplement their allowances.

But the stakes are much larger than pocket money. Researchers estimate that the market for fake Twitter followers was worth between $40 million and $360 million in 2013, and that the market for Facebook spam was worth $87 million to $390 million. Italian Internet security researcher Andrea Stroppa has suggested that the market for fake Facebook likes could exceed even that. International corporations like Pepsi, Coca-Cola, Mercedes-Benz, and Louis Vuitton have all been accused of employing click farms, and celebrities such as 50 Cent, Paris Hilton, and LeAnn Rimes, have been implicated in buying fake followers. During his 2012 presidential campaign, Mitt Romney gained more than 100,000 Twitter followers in a single weekend, despite averaging only 4,000 new followers a day previously. (His campaign denied having bought any fakes.) One Indonesian click farmer told me that he had funneled two million Facebook likes to a candidate in his nation’s hotly contested July 2014 presidential election.

Two of the most crucial rules of Facebook’s terms of service are: “You will not provide any false personal information on Facebook, or create an account for anyone other than yourself without permission,” and “You will not create more than one personal account.” The law of one person, one account is meant to guarantee that Facebook is the most real place on the Internet: The roughly six billion likes the company processes every day are supposed to be a quantification of homo sapien emotion. Other social media platforms, like Twitter, allow for more than one account per user, but, ultimately, the medium is predicated on the idea that its digital world is an accurate extension of the physical world.

Click farms jeopardize the existential foundation of social media: the idea that the interactions on it are between real people. Just as importantly, they undermine the assumption that advertisers can use the medium to efficiently reach real people who will shell out real money. More than $16 billion was spent worldwide on social media advertising in 2014; this money is the primary revenue for social media companies. If social media is no longer made up of people, what is it?

It was never Braggs’s intention to make a career of “onlining.” He dreamed of becoming a pilot and even went to flight school. (He still recalls the Leonardo da Vinci quote: “Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.”) Financial problems forced him to give up on his plan when he was in his early thirties, and, for nearly a decade, he survived on menial jobs: running a coffee stall at the bazaar, working construction, and chauffeuring tourists. One day, when he was driving a group of Koreans to a brothel—the destination for most of his customers—they offered him a turn with the high-class prostitute they were planning to employ. Braggs began searching for a way out.

Braggs got into onlining in 2011 after a friend who had struck it rich spamming gave him the software to start his own operation. When Braggs’s email spam business failed in 2012, he opened his own click farm, manually forging thousands of Facebook accounts and selling likes from them, incrementally hiring workers as his business grew. When he realized that he could make more money by supplying click farms with the products they needed—i.e., profiles and software to animate those profiles—he reorganized his business.

By July 2013, he was making phone verified accounts—or PVAs—full time. He hired 17 employees, including Casipong, and established round-the-clock shifts so his farm never went dark. Casipong guesses that she makes over 100 Facebook PVAs a day. Other employees average more than 150. Braggs sells PVAs for 70 cents; “premium” PVAs—accounts that are fleshed out with more than bare-bones biographical details—can be bought for $1.50.

Since his business began, Braggs has expanded into Yahoo, Gmail, and Twitter PVAs, and his customers have used the fake accounts in all sorts of scams: On the dating site Tinder, for example, Braggs said he believes seductive women solicited male users for pay-to-access porn sites. His biggest order, he told me, was for Chinese hackers trying to fleece the digital payment exchange Stellar; he hired every freelance worker he could find, but he was still only able to fulfill a small portion of it.

In many ways, Braggs’s account farm operates similarly to the outsourcing and industrial businesses that Cebu City is famous for. He relies on the infrastructure that carries the call center and technical support data to Cebu City from around the globe in order to pipe his forged profiles to his clients. He even benefits from cheap local resources—though instead of exploiting the Philippines’ old-growth rainforest timber, he processes SIM cards dropped off by men on motorcycles, paying a few cents for a card that would sell for $5 to $10 in the United States. Workers willing to do repetitive manual labor are not in short supply, either.

But Braggs’s account farm feels more like a startup than a developing-world sweatshop. Most of his employees are young IT university graduates infused with the excitement of beating the system. There is an office puppy named Hacker, and Braggs pays for a cook to prepare lunch for the employees every day. Casipong earns about $215 a month, significantly more than the minimum wage for a domestic helper, which is as low as $34 a month. Braggs pays his nightshift workers extra, and some of his employees reportedly choose to become nocturnal for the additional wages.

The Philippines has the highest rate of unemployment in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Casipong is aware of the alternative employment options: Cebu City is the “cybersex capital of the Philippines,” and illegal firework factories in the slums announce their presence every few weeks with a bang. Braggs’s employees seem genuinely happy; their main complaint was laggy Internet that disrupted the music they streamed while working. Many spoke of Braggs as a Horatio Alger–style role model. In the fictionalized biography Braggs maintains on the website of his account farm, he calls himself the Robin Hood of Facebook marketing, and this contrarian idealism extends to his general attitude about life. His hero is the tribal chieftain Lapu-Lapu—the namesake of his city—famous for slaying the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, who, in the name of capitalism and colonialism, was the first man to circumnavigate the globe. He has no desire to stay up all night answering questions about credit cards and Windows glitches for people on the other side of the world. Why shouldn’t he feel proud of providing decent salaries to 17 workers, or paying for the school fees of his girlfriend’s younger sister or the local kids’ basketball jerseys? He’s a self-made man, trained on YouTube tutorials and in chat rooms; to this day, he types hunt-and-peck style, never having learned QWERTY.

What he and click-farm managers are doing is not illegal in the Philippines. Facebook’s terms of service are not international law. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission and attorneys general from several states have legislated against fake reviews—false endorsements on Amazon, for example. But no formal ruling has been passed down on inauthentic likes. “Click farming raises serious consumer protection questions,” said Ian Ayres, a specialist in contract law and a professor at Yale’s law and business schools. “To participate as a buyer or a seller in the traditional click-farming market seems a clear wrong.” But the actual law is less explicit. And Braggs has his own business ethics: He’s not hacking anyone’s bank account, only offering a service that people are clamoring to pay for and providing for himself, his family, and his countrymen.

For years, Facebook encouraged brands to use social media as a free way to connect with fans. Companies would post content, and Facebook would show it to a large percentage of the people who had liked those companies, free of charge: This was the so-called organic reach of a post. But, over the last few years, with a noticeably precipitous drop in late 2013, Facebook has steadily decreased the organic reach of posts; now, when a company posts something, it only reaches about 6 percent of the profiles that have already liked that company, and Facebook plans to decrease that reach further. This has meant that companies struggle to access most of the fans they have accumulated unless they pay Facebook to advertise. But as Facebook becomes more of a paid billboard, click-farm bots can disrupt the efforts of companies that advertise with Facebook—and, sometimes, even render them pointless.

Here’s how this can happen. Second Floor Music, an independent, Manhattan-based jazz publishing company that represents critically acclaimed but lesser-known composers, was the kind of small business built on its history and reputation: Five Grammy certificates hung on the walls, and jazz legends and up-and-comers dropped by the studio to rehearse. It was not, however, exactly forward-leaning when it came to social media marketing. But it was also ideally positioned to take advantage of Facebook’s advertising services: Its products targeted a niche audience that was often hard to reach, but which Facebook, with its vast trove of personal data, could easily access.

So in September 2013, Second Floor Music launched a Facebook advertising campaign for the Facebook page of Jazz Lead Sheets, a Second Floor Music website that allowed customers to download sheet music and song recordings. Because more than one-third of Jazz Lead Sheets’ business came from international clients, Second Floor Music asked Facebook to put ads in front of people from around the world, and paid Facebook a few cents each time one of them “liked” the page for Jazz Lead Sheets.

A young jazz singer employed by Second Floor Music named Rachel Nash Bronstein ended up overseeing the Facebook campaign. At first, Bronstein was exhilarated by how fast the Facebook page gained fans, hundreds within weeks. But then she began to notice that the fan activity—liking posts, commenting, etc.—on the page had plummeted. When Bronstein examined the profiles, her heart sank. Many of them hailed from Iraq. A lot of the profiles didn’t display any English. None of them evidenced any interest in jazz.

It’s impossible to pinpoint how these profiles ended up fans of Jazz Lead Sheets. (Facebook is fiercely secretive about how its internal algorithms work.) But when Bronstein paid Facebook to place her advertisement, Facebook may have put the ads in front of accounts that had already liked thousands of pages, figuring that those accounts were more likely to click on the ad. And those accounts were likely run by click farms. (The average American user only likes 70 pages.) Because many fake accounts are programmed to disguise their mercenary activities by liking lots of pages (not just their client’s), these bots were primed to like the Jazz Lead Sheets page. And because click-farm accounts often are programmed to move in coordination, so that they are easier to control, having one bot like a page could have caused others to follow, setting off a cascade of fake likes.

These fake likes weren’t just an empty number. Whenever Second Floor Music posted content, Facebook’s algorithms placed it on the newsfeeds of a small, random sample of fans—the people who had liked Second Floor Music—and measured how many “engaged” with the content. High levels of engagement meant that the content was deemed interesting and redistributed to more fans for free—the main goal of most businesses that use social media is to reach this tipping point where content spreads virally. But the fake fans never engaged, depressing each post’s score and leaving it dead on arrival. The social media boost Bronstein had paid for never happened. Even worse, she now had thousands of fake fans who made it nearly impossible to reach her real fans. Bronstein struggled to get help from Facebook, reaching out repeatedly through help forums, but, in the end, she scrapped the original page and started again from scratch. Second Floor Music had effectively paid to ruin one of its flagship Facebook pages.

Across Facebook, well-intentioned companies and organizations have found themselves in this predicament. Small businesses ranging from Bay Area startups to Toronto magazine publishers have reported similar problems, and Internet forums and blogs are rife with related tales. Corporations with professional teams managing their Facebook pages and large advertising budgets seem to treat this kind of artificial appreciation as the price of doing business. But the side effects of click farms are a real threat to small businesses with slimmer margins for error and without the know-how to effectively target their ads. (It’s worth noting that small businesses are the focus of a Facebook marketing push that has involved nationwide outreach and efforts to streamline the company’s advertising platform. Since Second Floor Music’s first campaign, Facebook has made more tools available for advertisers to direct and monitor their ads. A year later, Bronstein ran another campaign that worked much better than the first.)

From January 2013 to February 2014, a global team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Software Systems, Microsoft’s and AT&T’s research labs, as well as Boston and Northeastern Universities, conducted an experiment designed to determine just how often advertising campaigns resulted in likes from fake profiles. The researchers ran ten Facebook advertising campaigns, and when they analyzed the likes resulting from those campaigns, they found that 1,867 of the 2,767 likes—or about 67 percent—appeared to be illegitimate. After being informed of these suspicions, Facebook corroborated much of the team’s work by erasing 1,730 of the likes. Sympathetic researchers from a study run by the online marketing website Search Engine Journal have suggested that targeted Facebook advertisements can yield suspicious likes at a rate above 50 percent. In the fall of 2014, Professor Emiliano De Cristofaro of the University College of London presented research which found that even a page explicitly labeled as fake gained followers—the vast majority presumably bots.

The bot buildup can even affect companies that aren’t advertising with Facebook, but are just passively hoping their pages gain real fans. In 2014, Harvard University’s Facebook fans were most engaged in Dhaka, Bangladesh. (They stated that they did not pay for likes.) A 2012 article in The New York Times suggested that as much as 70 percent of President Obama’s 19 million Twitter followers were fake. (His campaign denied buying followers.) Less prominent pages from across the world—from those belonging to the English metal band Red Seas Fire to international bloggers—have been spontaneously overwhelmed by bots that are attempting to mask their illicit activity by glomming on to real social media profiles.

This February, Facebook stated that about 7 percent of its then 1.39 billion accounts were fake or duplicate, and that up to 28 million were “undesirable”—used for activities like spamming. In August 2014, Twitter disclosed in filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission that 23 million—or 8.5 percent—of its 270 million accounts were automated.

Almost since their inception, social media companies have tried to limit this kind of digital-influence inflation. YouTube periodically examines videos with suspicious numbers of views. In December 2014, in what was called the “Instagram Rapture,” the platform cleaned up a number of accounts; Justin Bieber lost 15 percent of his followers. Facebook is constantly refining its defenses; the verification processes that take up so much of Casipong’s time are part of that effort. In some countries, Facebook has even requested pictures of government IDs from suspicious accounts. (They’ve mostly avoided this tactic in the United States, where it has triggered a backlash.) As a Facebook spokesperson said in a statement last August: “We have a real incentive to aggressively go after this activity because people want authentic connections on Facebook, and businesses use our platform to deliver real business results. Inauthentic interactions run counter to these goals, so we are constantly working to detect fraudulent activity and shut it down.” In April, the spokesperson continued: “Fraudulent activity has always been a tiny fraction of overall activity on our service, but recently we have developed new pattern recognition technologies that have mostly halted the major exchanges of fake like activity.”

At the same time, however, it is in the interest of Facebook and other platforms to downplay the severity of the problem. Twitter has recognized that more than 8 percent of its accounts are automated, but it says not all of these are malicious—i.e, run by click farms or used for spam—suggesting that many are used for legitimate purposes, like tweeting the scores of sports games. The company has reported that 5 percent of its accounts are malicious, but researchers have suggested the actual figure is at least double that.

These estimates are contentious because in 2014, more than 90 percent of Facebook’s $12.5 billion in revenue and about 90 percent of Twitter’s $1.4 billion in revenue came from advertising. If researchers are correct that advertising on social media leads to a high percentage of fake likes and fans and followers, the entire business model could be called into question by advertisers. What incentive do companies have to buy ads that target digital ghosts? As Internet security researcher Stroppa said, “The worth of Twitter is based on their active and total numbers of accounts. If they ban fake profiles, then they will lose an important percentage of their user base.” Brands have begun to report dissatisfaction with Facebook marketing, wrote Nate Elliott, a vice president for the technology and market research company Forrester Research, in an email. “If fake profiles are a widespread problem, then it may turn out Facebook’s value to marketers is even lower than we thought.”

Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms claim to successfully police their populations, but evidence suggests otherwise. The Max Planck team found that more than 90 percent of accounts they flagged as “black market” were not eliminated after four months, even though Facebook had erased many of the fake likes that these accounts had created. De Cristofaro found that Facebook caught less than 1 percent of the fake profiles he investigated. The number was even lower for high-quality accounts: For the month that he monitored 621 active profiles from a high-end click farm, only one was canceled. When I looked through the accounts managed by Braggs’s account farm and several other click farms, time-stamps revealed that the majority had been lurking on the network for several years. Many had even attracted real friends, either through automation or because their profile pictures had intrigued actual people; attractive women created by Braggs’s account farm often get approached with explicit overtures. (Unless clients specify other identities for PVAs, Braggs instructs his workers to make sexy women.)

And just as onliners quickly shifted when email spam was no longer viable, click farms have wiggled away from efforts to rein them in. To my eye, Braggs’s “premium” PVAs are almost impossible to differentiate from the real deal. (Casipong fills the photo albums of her premium PVAs with pictures that remind her of one of her favorite blogs, Humans of New York, and adds quotes like “hakuna matata,” which she has no idea comes from The Lion King.) Experts believe that without computer-aided analysis, this extra camouflage makes it almost impossible to finger any click farmer’s couture bot.

If Facebook comes to suspect that Ashley Nivens is not, in fact, a real person, and suspends her account, Braggs will have Casipong unearth the appropriate SIM card from the tens of thousands of cards organized and stacked around Braggs’s shop, insert it into a phone, and answer Facebook’s text message: Yes, she is a human. “Basically,” Braggs said when we met last September, “there’s nothing Facebook can do to stop me.” Facebook has shut down his personal account, but Braggs laughs it off: “Why would I need one Facebook account when I’ve got thousands?” The main limiting factor for his business is a somewhat unpredictable supply of SIM cards.

Last September, Braggs drove out of Lapu-Lapu City to one of the new luxury subdivisions springing up amid the wetlands and mangrove forests. He had purchased a house there and construction was underway. The streets were lined with boxy, concrete, two-story houses fronted by grass lawns—a Philippine version of the American dream, but with half the square footage of their Western counterparts and with roving goats nibbling their shrubbery. It is here that the ex-pats who run the nearby factories live.

The house was Braggs’s reward for working weekends and never taking a vacation. He had been so busy that two months had passed since he had visited, and he had to argue with the guards to be let into the gated community. The lawn outside Braggs’s house was chest-high, with saplings rising above the brush. His girlfriend—the first worker at his click farm—followed behind as Braggs pushed through the young jungle. This was the woman he would marry. This was where his children would be raised. This was where he would move his account farm once the electricity was turned on. The exterior of the house was finished, but the interior was bare. He stopped at the front door of his new home and patted his pocket, worried that he had forgotten the key.

It seems impossible that Facebook, with its army of elite coders and multibillion-dollar war chest, won’t eventually crush Braggs. The company knows his real name. It barrages his inboxes with cease-and-desist orders. But he’s hopeful. “Every system is made by humans,” Braggs told me, “so there is always a way to beat it.”