Have we reached peak green juice? The New York Times' Brooks Barnes suggests as much in a recent story about what a haute-hippie refuge in California is bringing to an already over-saturated market:

With every mini-mall, gas station and gym in Los Angeles now boasting a juice bar, or so it seems, the truly cutting-edge folks need to raise the ante to the point of ridiculousness. Kale-avocado-dandelion-cucumber-caraway-seed-jalapeño-heirloom-pear smoothie? Snore.

When the “Style” section not only identifies a trend, but deems it passé, it’s a safe bet it has indeed run its course. But it’s not just glorified cold vegetable soup that’s lost its allure. The pseudoscience that persists more generally in America is losing its cultural cachet.

In recent years, health trends became status signifiers to which mainstream Americans aspired. A high-end health food store grew into a supermarket-chain juggernaut. Designer clothing is now yoga-wear. Refusing to vaccinate one’s children, or to eat gluten, became at one and the same time ways to announce that one is upscale, and ways to convey an ethical commitment to healthy living. It wasn’t about being snobbish toward families who consume “juice” drinks. It was about tsk-tsking their choices while slurping an $8 bottle of agave-sweetened, cold-pressed… fine, juice drink, but at least one that comes in a BPA-free bottle. “Healthy” living became associated with being upper class, and therefore glamorous. The pseudoscience embraced by the rich—a group who also have superior access to actual healthy living, as in proper medical care, safe places to exercise, and so forth—is now, in turn, marketed to the rest of the population.

Guardian fashion columnist Hadley Freeman recently railed against lifestyle journalism’s “wellness” turn:

Wellness bloggers are increasingly numerous, astonishingly popular and embarrassingly feted by the media which never can resist attractive young women (who make up the most prominent members of this demographic) talking about food and being photographed nibbling on a strawberry…. They usually have a story about how they fell ill and cured themselves through their diet.

But the backlash has begun. As Freeman noted, “a new genre of journalism has risen up in response to a growing trend,” consisting of articles “debunking quacky pseudoscience bloggers.” She cited Belle Gibson, the clean-eating blogger who cured what turned out to be non-existent cancer, and Vani “Food Babe” Hari, who also turns out to be full of something other than organic strawberry, as examples of discredited advice-givers. Freeman might have also mentioned Dr. Oz, and indeed does discuss him in a later column. Photogenic men, and photogenic people with medical expertise, have also entered the pseudoscience game, and it’s just as much fun to watch their downfalls. That said, there is a gender dimension to this issue, given the tremendous (if often unstated) overlap between dubious health advice and beauty tips.

There are some indications that lifestyle journalism itself is losing patience with pseudoscience. Cosmopolitan, of all places, recently published a personal essay by a woman who’s given up snake oil and gone in for “Western medicine, which has saved my life twice.” Even outlets that had been its greatest proponents may be tiring of it. Beauty blog Into The Gloss, so often a peddler of gorgeously packaged Grade A pseudoscience, recently posted something about parabens being harmless cosmetics preservatives. And Gwyneth Paltrow took a break from detox-promotion to (awkwardly) raise awareness of food insecurity, something that is, unlike the amorphous “toxin,” a real issue.

Why the shift toward reason? The scientific evidence against quack theories is hardly new, after all. I suspect there are two related reasons for the decline of pseudoscience: an increase in awareness, and a decrease in trendiness.

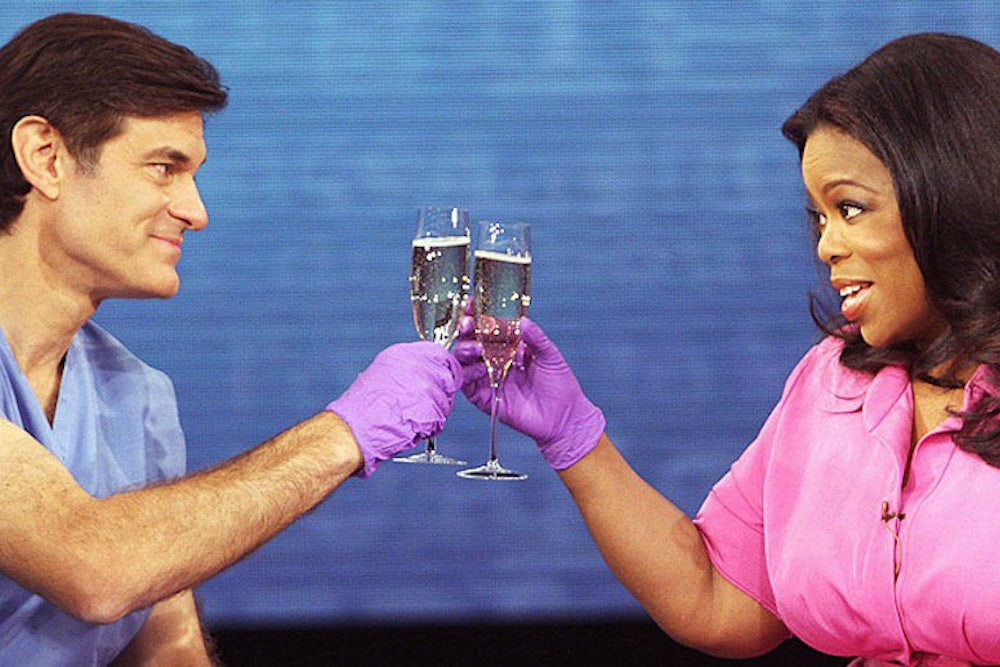

As pseudoscience has become more popular, the threat it sometimes poses—not just to oneself, but to society at large—has become more widely known. The measles outbreaks has caused genuine, legitimate fear, inspiring otherwise apolitical parents to rail against anti-vaxxers and the celebrities, like Jenny McCarthy, who inspire them. Meanwhile, exposed fraudsters have bred disillusionment. Popular lifestyle blogger “The Blonde Vegan” revealed that she wasn’t extra-healthy but actually suffering from orthorexia; she gave up veganism (if not snake-oil peddling) and now calls herself “The Balanced Blonde.” Then there’s Dr. Oz, whose high profile quackery recently inspired ten fellow doctors to ask Columbia University to fire him, and now Oprah’s also done with him. When controversies like these get publicity, it reminds all of us, tastemakers included, that actions taken in the name of health can be detrimental to wellbeing.

Nutritional pseudoscience may be the first to fall. The ingredient-purity obsession has inspired a backlash from people citing the social benefits of notturning every meal into an ingredient-by-ingredient research project. In a recent New York Times op-ed, “Eat Up. You’ll Be Happier,” Pamela Druckerman argues that we should eat like the French, but not so as to fit into a size deux:

Choosy eating interferes with another key aspect of French mealtimes: the shared experience of food. In France, "eating does not have the sole purpose of nourishing the biological body but also and above all of nourishing the social bond," writes the social psychologist Estelle Masson in "Selective Eating."

Along the same lines, Alan Levinovitz, author of a new book debunking gluten-panic, explained the broader social impact of ingredient fixations in a recent interview:

The gluten-free movement really threatens food culture and our relationship with food. People are starting to think about diet as the main way to optimize their health, and as a consequence, their ability to sit down and enjoy a meal is diminishing.

The very concept of “clean eating” is, as L.V. Anderson wrote last year in Slate, not just used to sell pseudoscientific cleansing plans, but also “gives [one’s diet] a misplaced and emotionally charged moral cast.” While few of us are going to confront full-blown orthorexia, many more will have our lives negatively impacted by ingredients that we or our loved ones are needlessly shunning. Lighthearted mockery of hippie-chic elites—the strain taking us from David Brooks’s “Bobos” through to “Portlandia”—is giving way to more serious concerns about the dangers of that lifestyle.

All this attention to pseudoscience, commercially and journalistically, may be having a different kind of deterrent effect: It's too popular to be cool anymore. Once “wellness” becomes a thing in suburban Middle America, it stops being so in, say, the L.A. yoga mom subculture. Once clean eating goes from Gwyneth to Pepsi, it’s lost its air of exclusivity. The committed quacks won't budge, but once pseudoscience isn't a way of signaling that one is on the cutting edge, it loses its allure among the elites—the ones whose cultural and financial clout led to its popularity in the first place.

The two reasons for pseudoscience's decline—changing lifestyle trends, and the rise of scientific reason—aren't mutually exclusive. It’s possible to share Michael Pollan’s queasiness over the corporate cooption of “natural” out of snobbery and out of a noble rejection of greenwashing. But as Americans realize it's no longer necessary to sacrifice chic in order to embrace reason, pseudoscience will lose many more fans. That will benefit all of us—except, perhaps, those who earn a living selling green juice.