This January, in his State of the Union address, President Obama did something that no president has ever done in a venue of this importance: He called for paid family leave.

“We are the only advanced country on Earth that doesn’t guarantee paid sick leave or paid maternity leave to our workers. Forty-three million workers have no paid sick leave—forty-three million. Think about that,” he said.

The White House believes it has an opportunity to push for comprehensive paid leave. “The economy is recovering,” Obama adviser Valerie Jarrett told me in April. “Employers can take a deep breath, step back, and say, ‘Now that we’ve survived and come out of a very challenging time, what can we do to ensure our companies are globally competitive?’ Plus there’s the change in the demography of the workplace—now women comprise over half of the college-educated workplace.” The time, it seems, is now, although some might wonder what took so long.

It is astonishing, when you think about it, that paid leave has only entered the national political discourse in a meaningful way in 2015, with little help until recently from major political figures. The price paid by Americans who lack the right to take paid time off to recover from childbirth, to care for newborns, or to respond to the calamities of fallible health—our own and that of our loved ones—could not be higher. We have no choice but to neglect the needs of our families, or our work, or both. After unemployment, births and family illnesses are a leading cause of what is known as “poverty spells”—when one’s income dips below the minimum needed to afford food and shelter. Nationally, about 9 percent of workers who take time to care for a loved one end up on public assistance, and only 12 percent of private-sector workers are covered by formal paid leave policies, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Compensation Survey.

The first, and to date, last time a sitting president took action on family leave was February 5, 1993, when Bill Clinton signed the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), making it his first law in office. “Family medical leave has always had the support of a majority of Americans, from every part of the country, from every walk of life, from both political parties,” he said. “But some people opposed it. And they were powerful, and it took eight years and two vetoes to make this legislation the law of the land. Now millions of our people will no longer have to choose between their jobs and their families.” A noble and forward-thinking sentiment, but it wasn’t quite true. The FMLA only guarantees the ability to return to a job after taking unpaid leave and not to everyone: Only workers who have been with the same employer for at least twelve months qualify. That and other concessions made to small business interests mean that 40 percent of all U.S. workers have no job-protected leave at all.

In the 22 years since the FMLA became law, the federal government has gone no further. But circumstances have not remained in stasis. Our economy, culture, and society have seen dramatic changes. Working is a choice for some women, but a necessity for most. A Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census data found that the percentage of married women with children who were the primary financial provider in their household had increased by at least one third since 1994, a year after Clinton signed the FMLA. (Single mothers, according to the analysis, are “breadwinners” in 25 percent of U.S. households.)

Even though everyone would gain from paid leave, it is women who disproportionately carry the burden of its absence. Of course, the fact that paid leave would benefit women—indeed, would go far in addressing what many have called the unfinished business of feminism—may be the reason why we don’t have it. “The reluctance of conservatives to incentivize women’s work,” Johns Hopkins labor sociologist Andrew Cherlin told me, “is the only remaining barrier to consensus” on paid leave. “When it gets right down to it, many conservative social policymakers don’t want to further discourage mothers from staying home. That’s the basic reason we don’t have [paid] family leave here when we have it everywhere else.” It is not the expense of paid leave, as conservatives often support tax credits for child care that cost far more but benefit stay-at-home mothers. Fears of gender equality are at play here, as they always are.

As a society, we are consumed by the idea of bringing work and life into balance. But too often we talk only of the individual, personal solutions required to make that possible, rather than the basic structural support that is actually needed. Our laws rest on an antiquated and broken family structure: husband at work, wife at home; one person to make a living, the other to make a family. That vision of society might be sweetly nostalgic to some, but it is science fiction to most. The national myth of rugged independence dictates that if we can’t manage the dual demands of workplace and home, it is a personal failing. We didn’t lean in. We’re not career-minded enough. We’re bad parents. This is a false construct: The system is set up for us to fail.

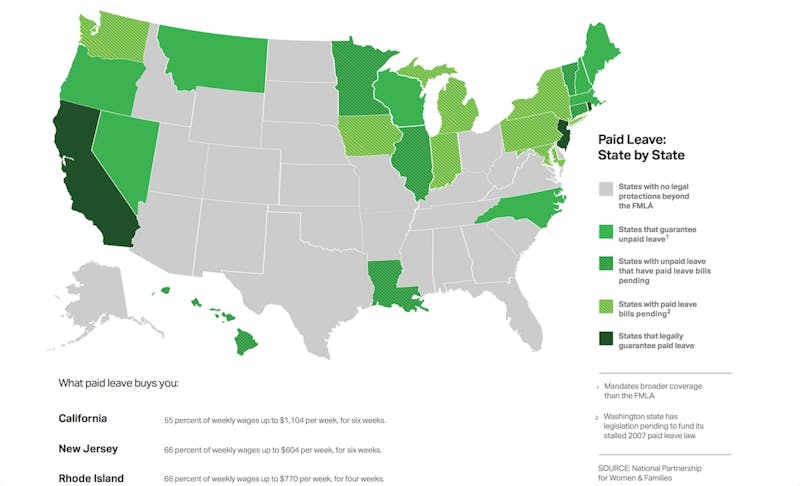

Three states currently mandate paid leave—California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—and what those states have discovered can serve as models for the rest of the country: Workers are more likely to return to work if they have paid leave, reducing turnover costs (what it takes to hire and train a replacement), which can reach $18,000 or more; women who take paid leave after having a baby are more likely to be employed the following year—and actually report higher wages than women who don’t take leave. (They also raise healthier babies.)

Paid leave is no longer just a woman’s issue. It cannot be. As we have begun to rely on women as earners, so too have men become more important as fathers. Paid leave allows—and insists—that men become active parents from birth. When leave with pay is offered to new fathers, they are more involved in caregiving not just at the beginning of life, but throughout childhood. Are these not the “family values” we profess to embody but have yet to actually support?

In April, at the Women In The World summit in New York, Hillary Clinton delivered the first major speech of her presidential campaign. It was no accident that her opening policy point that day was to call for paid leave. “It is outrageous that America is the only country in the developed world that doesn’t guarantee paid leave to mothers of newborns,” she said, calling it “hard to believe” that so many American women still “pay a price for being mothers.” She told the crowd a story about a nurse at the hospital where her granddaughter Charlotte was born who had thanked her for “fighting for paid family leave.” Either the story was embellished or the nurse wasn’t well informed: Paid leave has never been a significant priority for Clinton as a presidential candidate, secretary of state, senator, or first lady. Political pragmatism always led her to other fights. Now it’s leading her here.

Political memories are short, but if we can cast our minds back to the 2008 campaign, when Obama and Clinton were vying for the nomination, proposals regarding the country’s work-family dilemma were largely absent from the thousands of hours of speeches the two candidates gave. It wasn’t on Obama’s agenda for change, nor did it suit Clinton’s efforts to be perceived as more than the first serious female contender for highest office. Even three years ago, during his reelection campaign, Obama was still mostly silent on the issue. As for Clinton, as recently as last June, she dismissed paid leave policy at a CNN town hall meeting, saying that it should be implemented “eventually,” but that it still wasn’t politically expedient. This year, though, on Mother’s Day, the Clinton campaign released a video that featured nostalgic images of her mother to highlight the paid leave portion of her Women in the World speech.

But Clinton, like Obama and other national Democrats, is playing catch-up: The National Partnership for Women & Families, using predictive modeling, found that candidates from both parties who supported these issues (along with equal pay for men and women and paid sick day initiatives) were 8 percent more likely to win than those that do not; the Rockefeller Family Fund found that 64 percent of American voters said they’d be more likely to vote for a candidate who supported paid leave and fair pay. Even a majority of Republican women support federal paid leave. In California, more than three-quarters of conservatives favor paid leave, and they’ve been living with it since 2002.

We have not reached this political moment quickly or easily. The struggle to guarantee unpaid leave was arduous and not without setbacks. In 1986, Democratic Representative Pat Schroeder introduced the nation’s first family leave bill, the Parental Disability and Leave Act. Workers would not be paid under her bill, but if they had to take leave, all businesses, regardless of size, would be legally bound to protect their jobs. It failed to pass. Schroeder brought another, similar bill forward in 1987, although she narrowed its scope to businesses with more than 15 workers. It failed again. Her next bill in 1988 raised the limit to companies with more than 50 employees; it died, too, when Democrats in the Senate failed to gather enough support to force a cloture vote on a companion bill.

In 1990, the same bill passed both houses of Congress, but President George H.W. Bush vetoed it—and the attempt to override the veto came up 53 votes short. Bush said he had a duty to ensure “federal policies do not stifle the creation of new jobs, nor result in the elimination of existing jobs.” In 1991, family leave bills again passed in the Senate and House and were sent to conference to be reconciled. During a contentious debate on the House version of the bill, Schroeder asked, “What’s the administration’s family leave program? Home Alone,” a reference to the John Hughes movie. “If you want to have children, leave them home alone.” Robert H. Michel, the minority leader, replied by calling paid leave “rigid and simplistic” and “a big government dinosaur out of the past.” A compromise bill passed the following year, only to be vetoed again.

In 1993, when the FMLA finally passed, Republican Representative John Boehner, serving his first term in Congress, predicted it would cause the “demise” of U.S. business. “People thought we were crazy, verging on communism, it was going to be the end of free enterprise,” said Debra L. Ness, president of the National Partnership for Women & Families. Yet only a year after it was enacted, The Washington Post noted, “So far none of the predictions about administrative nightmares, ruinous costs to business and a decline in national productivity has been right.” Of the 561 valid complaints received by the U.S. Department of Labor in the law’s first year, the Post reported, “Ninety percent of these were settled easily, usually with a single phone call to the employer.” (Members of Congress set their own paid leave policies, and Boehner, the speaker, is the only sitting representative known to offer just two weeks paid maternity or paternity leave to his staff. Most congressional offices guarantee between six and twelve weeks.)

Meanwhile in California, which had passed its own version of the FMLA in 1991, there was a push to move beyond unpaid leave. In 1999, the state passed the “kin care” provision that required employers who provide paid sick leave to allow their employees to use up to half of their annual allotment to care for a sick child, parent, or spouse. “We’re not in a new century yet—but when it comes to labor legislation in California, it’s starting to feel that way,” the San Francisco Chronicle declared. A full paid leave law passed in California in 2002. It required workers to receive roughly half their salary, capped at about $1,000 per week, for six weeks after a birth or the adoption of a child or to care for a seriously ill family member.

A 2011 poll of California businesses by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) examined ten years of paid leave in the state. Ninety-nine percent of the companies surveyed found that offering paid leave either had a neutral impact on morale or raised it; 93 percent found it reduced turnover or left it unchanged; and almost 90 percent of employers reported either a positive or no noticeable effect of paid leave on their businesses. The study’s only negative finding was that not enough workers knew about the policy.

The success of paid leave in California fueled a grassroots movement, one that has been making slow but steady progress on the state level. It hasn’t worked everywhere, though. In 2007 the state of Washington passed paid leave, guaranteeing workers on leave up to $250 a week. Unfortunately, the bill passed without specifying a revenue source, and eight years later, the program remains unfunded and has never been enacted.

New Jersey’s journey toward paid leave was no easier, but had a more positive outcome. A state bill first proposed in 2001 made little progress in the legislature. Seven years later, it took the political heft of labor unions, the online muscle of AARP, and pressure from voters of all political leanings, to finally enact paid leave. It helped to have a champion in office, one with a story. State Representative Stephen Sweeney’s daughter was born with Down syndrome, an experience that transformed him from “a classic stereotypical iron worker, the guy you saw running out to the bar at the end of the day,” to a politician who wrote the state’s paid leave bill himself. The bill covered two-thirds of a worker’s weekly wage, up to $524 for six weeks, and was entirely funded by employee contributions.

Even so, business groups pushed back. Jeff Stoller, vice president of the New Jersey Business & Industry Association (njbia), called paid leave “a major disaster for employers”; Phil Kirschner, the njbia’s president, called it “ludicrous” and “flashing a neon sign [to businesses] that says, ‘Don’t come here’”; Republican State Senator Kevin J. O’Toole acknowledged the need for paid leave, but said, “We have the heart for it,” just not “the wallet.” (The bill cost workers 64 cents a week out of their paychecks.)

After then-Governor Jon Corzine signed the bill, Chris Christie promised to overturn it during his campaign against Corzine. But Christie never followed through. The reason why is quite plain: As with California, most everyone loves paid leave. A recent study from the CEPR found that businesses, many of which strenuously opposed the policy, now believe paid leave has improved productivity and employee retention, decreasing turnover costs.

Like California, New Jersey has become a laboratory for paid leave, a success other states can measure and study. Eileen Appelbaum, a senior economist at CEPR who spent a year reviewing field interviews with New Jersey business owners and workers, told me that in 2013, the last thing legislators in Rhode Island saw before voting on a paid leave bill was a fact sheet she’d assembled on the lessons from New Jersey. The law passed, and Rhode Island, on the strength of such measurable success, became the third state to enact paid leave.

In a process reminiscent of the state-by-state march toward gay marriage, paid leave seems to be gaining momentum. Every December, the Family Values@Work Consortium, a coalition of 21 state groups that advocates for paid sick days and family leave insurance, holds its annual meeting at the Ford Foundation in New York. Several years ago, the meeting’s attendees fit around a conference table. Now they fill an auditorium. Ellen Bravo, who runs the consortium and who is perhaps the country’s most tenacious advocate for workplace policy reform, sees continuing success in the states as essential to achieving the policy nationwide. “It’s a tandem effort,” she told me, with “states paving the way toward federal success.” But the process remains slow and incomplete. “It seems very unfortunate that you can live in California, pay taxes into a program for 15 years, and then move across the border to Oregon and not get it,” said Heather Boushey, director of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

The utility closet door in senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s office can barely close—there’s a double stroller jammed inside. A framed onesie hangs in the reception area, with a magic-markered affirmation that “NY ♥ the Family Act.” When Gillibrand was an attorney at Boies, Schiller & Flexner in New York in 2001, she learned that the firm, which has over 200 lawyers, had no maternity leave policy. “So I wrote it myself right after I had my first baby,” she told me over lunch near Capitol Hill in April. There’s usually a staff member on leave in Gillibrand’s office—her chief of staff has three kids, and her head of communications had his first child a little over a year ago. The senator routinely fetches her children from school before a vote so she doesn’t get stuck on the hill during afterschool pickup. (They hang out in Harry Reid’s office.)

Gillibrand is the author and, along with Representative Rosa DeLauro, co-sponsor of the Family Act, the nation’s first federal paid leave bill. The Family Act, if made law, would create a fund that works like Social Security—in fact, it would function as a trust within the existing Social Security system. Employees and employers would contribute two cents on every $10 earned. Like Social Security, there would be a wage cap—a worker can only be taxed on income of up to about $113,700 a year, which means a maximum annual contribution of about $225. The fund would cover workers for twelve weeks, for the birth or adoption of a child, to care for a seriously ill family member, or in case of one’s own medical condition, as already defined under the FMLA. For those twelve weeks a person would collect 66 percent of his or her monthly wages, up to a maximum of $1,000 a week. “It’s the next social safety net that needs to be fought for,” Gillibrand said.

The bill still has no Republican co-sponsors, and while advocates don’t oppose it, many have simply ignored it. Last summer, when a panel convened to discuss paid leave at Demos, the New York-based think tank, the Family Act was not mentioned by anyone in attendance—except when I asked a question about it. Given the current political climate, advocates believe any plan that costs anything, no matter how much, or who pays for it, is dead on arrival, especially if it’s from the Democratic minority. But the reluctance to take the bill seriously has eased significantly in the past year. “We will continue to see this tremendous momentum, and we’ll see this on the national bill,” Ellen Bravo told me. “Passage is in sight. It’s entirely doable.” Her optimism may sound more like cheerleading than cool-eyed assessment, but in my interviews with Bravo over the last few years, I’ve never heard her say anything like it before. That can’t be taken lightly.

When politicians and lobbyists oppose paid leave their main tactic is to attack it as anti-business. In Connecticut, for example, where a bill is currently advancing through the state house, organized efforts to fight the paid leave trust fund have been taken up largely by business lobbying groups. In November, the Connecticut Business & Industry Association released a report called “Should Connecticut Adopt a Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Program? An Alternate View,” alleging that family leave would cost “upwards of a billion dollars on a new state-mandated benefit” and would fail to “solve a problem but create new, unintended ones with an impact on jobs and economic opportunities.” Eric Gjede, a lobbyist with the group, wrote on its website that paid leave policy constituted a “full-scale mandate war against the mom-and-pop” businesses. These are the same false arguments made against the FMLA; the same arguments, Bravo pointed out to me, against worker regulations proposed in 1911 after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. It is the same argument used every time the government has tried to introduce notions of fairness in business, especially when women are concerned.

In April, I met Jack Mozloom, a straight-talker in an oversize navy blue suit who runs communications for the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB). The NFIB is a Washington, D.C.-based lobbying group whose stated mission is to help its 350,000 members “promote and protect your right to own, operate and grow your business.” When asked about mandated paid leave, Mozloom grinned. “We hate that,” he said.

Mozloom told me a story about an auto repair shop in New Jersey. The owner has eight employees, and the business is profitable only if it can repair 200 cars per week. “He only gets paid if the workers are there providing a service,” he said. If a worker goes on leave to care for his family, the shop repairs fewer cars and earns less money. “Paid leave says you gotta pay them if they never show up in the first place?” He shook his head in disgust.

The logic seems straightforward enough: Paying people for days they don’t work is bad for the bottom line. The problem with this logic is that if it were true, businesses would be against paid leave. But most of them are not. The Small Business Majority, a Washington, D.C. lobbying group that partners with local chambers of commerce and rotary clubs, polled small businesses nationwide in 2013 and found that about two-thirds either support or don’t oppose paid leave. When employers have to contribute financially toward it, support drops, though a plurality remains in favor, 45–41. “When you look at the polling,” John Arensmeyer, the group’s founder and CEO, told me, “the opposition is more ideological then pragmatic.”

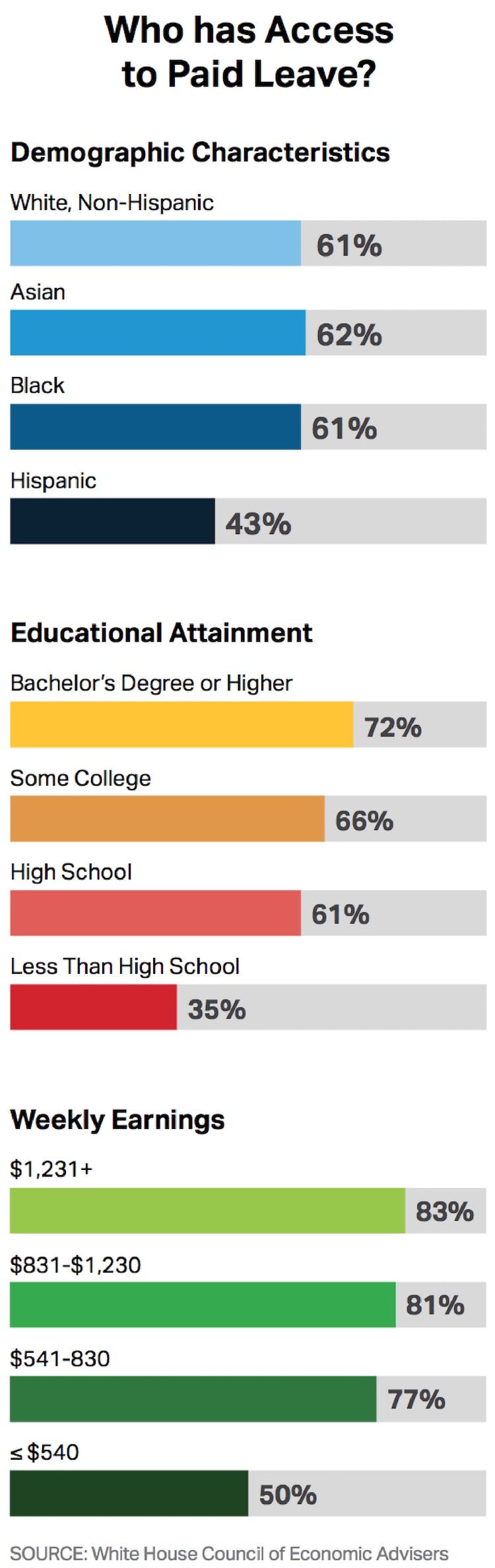

Many companies do provide some form of paid leave, at least to new mothers. But the lowest wage earners are the least likely to have that opportunity. The whiter the collar, the better the benefits. Which means people who work at Goldman Sachs can expect a solid four months of new parenting, with pay. In March, Vodaphone mandated 16 weeks of paid maternity leave for all employees worldwide. A couple of weeks later, Microsoft announced it would no longer work with businesses that failed to provide at least 15 days of paid leave per year, a move that directly affects its business partners as well as tens of thousands of contract workers. In April, McDonald’s offered paid leave at 1,500 of its nonfranchised restaurants. And as of May 1, new parents at Johnson & Johnson can take eight weeks of paid leave during the first year of a child’s birth or adoption. This is in addition to the nine weeks of paid maternity leave the company already provided.

The unfinished business of feminism, it turns out, has become the unfinished business of business. Tom Nides, Hillary Clinton’s former deputy secretary of state for management and resources, and now a vice chairman at Morgan Stanley, has been a vocal advocate for paid leave policy. “If the business community rallies around this and does what Microsoft just did, quite frankly, more companies will stand up and talk about this issue,” Nides told me.

Now even legislators are warming to the idea. When the Family Act was first introduced last year, Heather Boushey told me she thought it wouldn’t “ever go anywhere—we can’t even imagine doing it” under the current congressional leadership. Gillibrand’s fellow senators apparently agreed: only six were willing to co-sponsor the bill. But now, Boushey said, “You’ve seen people get more and more comfortable with the idea.” Indeed, 13 senators have signed onto the bill, which has been referred to the Senate Finance Committee; in the House, 88 members have joined (all Democrats), with a referral to the Ways and Means Committee—a far better showing than when the bill was put forward last year. “It’s not going to happen overnight,” Rosa DeLauro told me. But it helps, she said, that the White House has made paid leave a priority.

In September, U.S. Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez implemented a new program that would offer $500,000 to states to conduct paid leave feasibility studies. “These federal grants will further our understanding of this issue,” Perez said. The amount of money is insignificant. (“I’ve never seen more applications for such a small amount of money,” Perez has said.) But it may be a sign of things to come. “Federal paid leave is a ‘when’ question, not an ‘if’ question,” Perez told The Washington Post. Then in January, Obama signed a memorandum, which has the same legal effect as an executive order, that gave federal workers six weeks of paid leave. And this spring, Perez and Valerie Jarrett embarked on a “Lead on Leave” tour through cities and states that are considering paid leave or have already implemented it. Obama wants to lead by example, Jarrett told me. “Our hope is that as we build momentum, the Congress will see we have to build a twenty-first century workplace that reflects the values and priorities of the twenty-first century worker.”

Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, has yet to release a proposal for a leave plan. A clue to her intentions, however, can be found in the hiring of Ann O’Leary, a paid leave expert and advocate, as one of her top three advisers. In 2010, O’Leary published “Family Security Insurance: A New Foundation for Economic Security,” a policy platform that suggested the social insurance system was best situated “to provide for income replacement when people take time off from work for health and caregiving reason”: a plan and argument that sounds like testimony in support of Gillibrand’s Family Act. “We have to update our employment policies and our social insurance policies to work and make sure people have the income they need to make to support families and caregiving,” O’Leary, whom I spoke with in April, told me. “At the forefront of the [Clinton] campaign,” she said, will be “a suite of issues related to how middle-class families have both economic stability and opportunities for their children.” Regardless of what form these policies take, it seems apparent that Clinton will bring family leave into the presidential debate. “Every presidential candidate should be asked if he or she supports paid leave and if not, why not,” Gillibrand told me.

Clinton’s campaign is well situated to work in tandem with the White House efforts, which while minor in practice are major in rhetoric—ironic, considering when the two candidates faced off in 2008 the issue was all but invisible. “The administration has helped to set the parameters in the next election,” Debra L. Ness of the National Partnership for Women & Families told me. “All these currents are moving in the same direction toward the time when we are going to have a very visible national debate.”

Whether it’s via the Family Act or a different solution, under this Congress or another, no one yet knows. But the voters have made it clear that our leaders must reconcile the competing responsibilities of work and family. They are, perhaps, finally able to hear the insistent hum of discontent. And if they truly listen—and if they have the courage to act—in 2016 there may be change instead of just chatter.