Plenty of writers inspire fierce devotion in their readers—the David Foster Wallace acolytes, with their duct-taped copies of Infinite Jest, come to mind, as do the smug objectivists dressed in tech-world casual who owe their entire worldview to Ayn Rand. But no one converts the uninitiated into devout believers as suddenly and as vertiginously as Clarice Lispector, the Latin American visionary, Ukrainian-Jewish mystic, and middle-class housewife and mother so revered by her Brazilian fans that she’s known by a single name: “Clarice.”

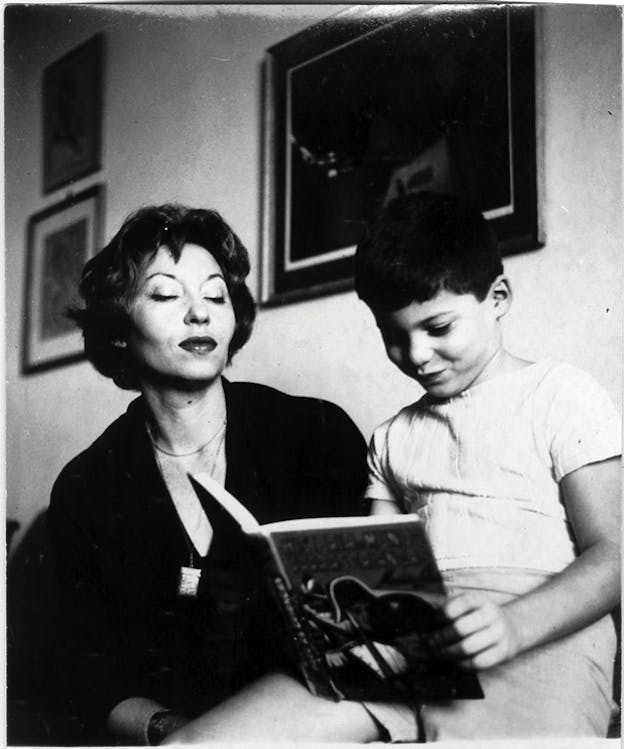

The Complete Stories, edited and introduced by Benjamin Moser and translated, with jarring beauty, by Katrina Dodson, continues the introduction of Lispector’s work to the English-speaking world that began with Moser’s 2009 biography Why This World. Lispector was a figure of glamour and mystery in her lifetime, a writer so singular that her fiction often seems without precedent and her biography can sound apocryphal. There is a telling anecdote in the novelist Colm Tóibín’s introduction to her last novel, The Hour of the Star: Around the same time Lispector was working on the book, a younger Brazilian novelist, José Castello, saw her peering into the window of a shop one day on the Avenida Copacabana, in Rio. Castello greeted Lispector, and she turned slowly away from the window to face him. “So it’s you,” she said mysteriously. Castello noticed that the window of the shop was empty except for a number of undressed mannequins. It was a jarring enough encounter that he would write about it later. “Clarice had a passion for the void,” he concluded.

Lispector’s thorny, relentlessly interior fiction—the narrator of her novel The Passion According to G.H. eats a dead cockroach in a maid’s room to try and get closer to God—was long considered too hermetic to translate. But thanks to Moser’s tireless advocacy of her work and the support of independent publisher New Directions in the United States and Penguin Classics in the United Kingdom, she’s now getting the Bolaño treatment—and the global acclaim she has long deserved.

Born in 1920 into the miseries of a Ukrainian shtetl—her mother contracted syphilis after being gang-raped by Russian soldiers before she was born; the family was cheated, starved, and forced to flee successive waves of pogroms before gaining passage in 1922 to Brazil on a steamer—Lispector was a foreigner in the only country she claimed as her own. “I belong to Brazil,” she once declared, but Brazil didn’t always reciprocate. She was entirely unknown to Brazil’s intellectual class when her first novel, Near to the Wild Heart, was published to breathless acclaim in 1943. “She felt a perfect animal inside of her,” Lispector wrote of the novel’s protagonist, Joana, a wild child who grows into a hot mess of a religious mystic, “full of contradictions, of selfishness and vitality.” This plotless spectacle of splintered consciousness has more in common with Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) than it does with Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; the title was cribbed from a passage, and Joana’s declarations are arrestingly surreal: “I will be as brutal and misshapen as a rock.”

Selfish vitality was a constant in Lispector’s own life, carrying her through early fame in literary Rio, where rumors swirled about her identity, to exile on the stultifying diplomatic circuit, where she was forced to play hostess—badly—in order to further her husband’s career. She faced rejection from afar by Brazil’s publishers, battled sleeping-pill and tranquilizer addictions, and was eventually rediscovered, in the 1960s, for the formal abandon of her late novels, as well as her weekly crônicas in the influential newspaper Jornal do Brasil.

The Complete Stories gathers together, in one volume, more than 80 short stories, essays, sketches, fragments (there’s even a one-act play), and the hybrid forms of fiction and personal essay that Lispector specialized in, from her first published story—she was 19 and a law student at the University of Brazil—to the pair of manuscripts left unfinished at her death, from ovarian cancer, in 1977. While this may sound like a literary grab bag, there is a remarkable coherence to the whole. Moser, in his introduction, calls the volume “a record of [a] woman’s entire life, written over a woman’s entire life.” This is true, but Lispector was no ordinary woman: She writes like a medieval saint who time-traveled to a high-rise apartment building in Rio and took up chain-smoking and visiting fortune-tellers.

The earliest stories in the collection, not surprisingly, come wrapped in more conventional guises: “The Triumph” records the observations of a young bourgeois woman whose husband, a frustrated writer, has left her after a blowup; “Obsession” is narrated by another young wife who finds herself tempted from the “straight path” of marriage, children, and family life by an armchair philosopher staying at the same rooming house where she’s gone to convalesce after catching typhoid fever. You can, however, see glimmers of the inner sight that would animate Lispector’s mature work—Luísa, the young wife in “The Triumph,” gains the upper hand when she rifles through her husband’s papers and discovers his “confession” that his mediocrity is his real torture, while the wife’s affair in “Obsession” leads not to liberation, but to a punishment that sounds like something out of Ovid’s Metamorphoses:

What matter am I made of in which elements and foundations for a thousand other lives mingle but never merge? I go down every path and still none is mine.

I have been sculpted into so many statues and haven’t frozen into place …

In the story “Jimmy and I,” the narrator’s first love is preempted by an examiner at school whose husky voice makes her “die of joy.” Her explanation to Jimmy, that humans are “simple animals,” serves only to end their relationship. Lispector’s affinity for animals—“I have a horse inside me that rarely manifests itself,” she wrote in the 1974 essay “Dry Sketch of Horses”—and their unapologetic appetites is part of what lends her work its shamanic, premodern qualities. A black buffalo in a zoo absolves one protagonist with its radiating hatred (“The Buffalo”), and an egg cracked on a frying pan becomes an excuse (“The Chicken and the Egg”) for a philosophical investigation into fertility, domesticity, and the inner life of the chicken: “The egg is the cross the chicken bears in life. The egg is the chicken’s unattainable dream.”

Given what Lispector can summon from a domestic hen, it’s not a surprise that her finest stories—many are not traditional “stories” at all, but lyric essays she published in the Brazilian journals and newspapers that first gave her a national audience—are astonishingly alive to the forces working underneath the ordinary “stream of life.” “Love” follows Ana, another one of Lispector’s women suffering from the strains of the marriage plot, from a disturbing encounter on a tram with a blind man chewing gum (he “plunged the world into dark voraciousness”) into Rio’s overgrown botanical garden. Ana, on the verge of nervous collapse, has surrendered to the day’s “unstable hour,” and she vibrates with second sight:

In the trees the fruits were black, sweet like honey. On the ground were dried pits full of circumvolutions, like little rotting brains. The bench was stained with purple juices. With intense gentleness the waters murmured. Clinging to the tree trunk were the luxurious limbs of a spider. The cruelty of the world was peaceful. The murder was deep. And death was not what we thought.

Laura, the protagonist of “The Imitation of the Rose,” is similarly on the verge of a breakdown, although it’s her fear of Christ and the demands of his perfection that bring on her spells of supernatural fear and trembling. “It’s back, Armando,” she warns her husband, and the line is as terrifying as anything in Poe. In “The Disasters of Sofia,” a schoolgirl’s attraction for her male teacher is threatened by his sudden interest in an essay that she’s written in an exam book, and she realizes, watching him in the empty classroom, that he is “very big and very ugly” but also “the man of my life.”

If Castello was right about Lispector and the void, then it wasn’t a “passion” in the sense we often use the word today—as in “Finding Your Passion in Twelve Easy Steps”—but passion as a sacrifice, a discipline, a submission to the disorder of the irrational for the sake of making a truer and more transformational art. In her late story “The Departure of the Train,” Lispector’s protagonist, Angela, has an epiphany that helps her go on despite the ever-present urge to commit suicide:

Somewhere there’s something written on the wall. And it’s for me, thought Angela. From the flames of Hell a fresh telegram will arrive for me. And never again will my hope be disappointed. Never. Never again.

You could call Lispector’s stories telegraphs from the flames of hell, but that would discount how innocent and funny they can be. Manna from the shtetl? Prayers at the high-rise window before the tranquilizers kick in? You will not be disappointed if you read The Complete Stories. It might even become your bible.