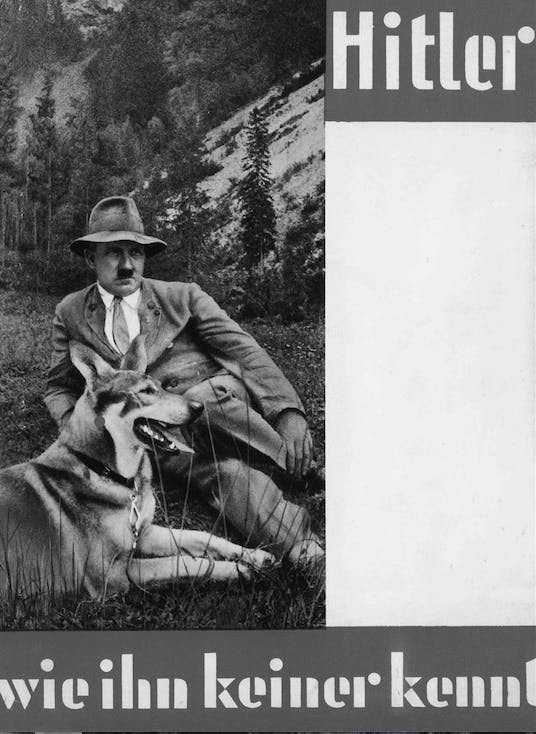

On March 16, 1941—with European cities ablaze and Jews being herded into ghettos—the New York Times Magazine featured an illustrated story on Adolf Hitler’s retreat in the Berchtesgaden Alps. Adopting a neutral tone, correspondent C. Brooks Peters noted that historians of the future would do well to look at the importance of “the Führer’s private and personal domain,” where discussions about the war front were interspersed with “strolls with his three sheep dogs along majestic mountain trails.”

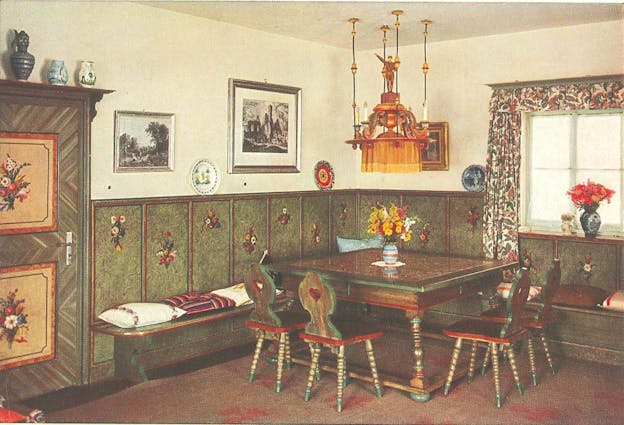

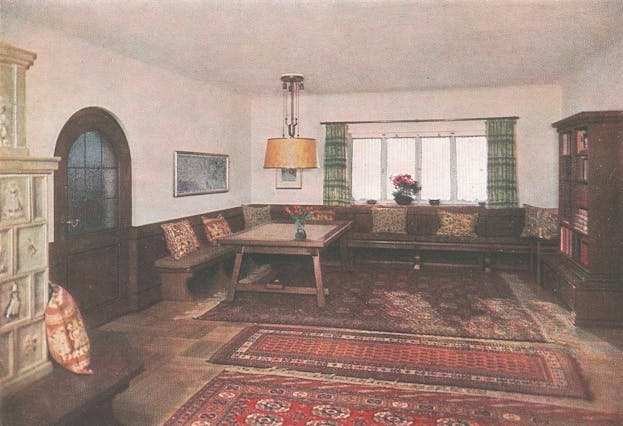

For more than 70 years, we have ignored Peters’s call to take Hitler’s domestic spaces seriously. When we think of the stage sets of Hitler’s political power, we are more apt to envision the Nuremberg Rally Grounds than his living room. Yet it was through the architecture, design and media depictions of his homes that the Nazi regime fostered a myth of the private Hitler as peaceable homebody and good neighbor. In the years leading up to World War II, this image was used strategically and effectively, both within Germany and abroad, to distance the dictator from his violent and cruel policies. Even after the war began, the favorable impression of the off-duty Führer playing with dogs and children did not immediately fade.

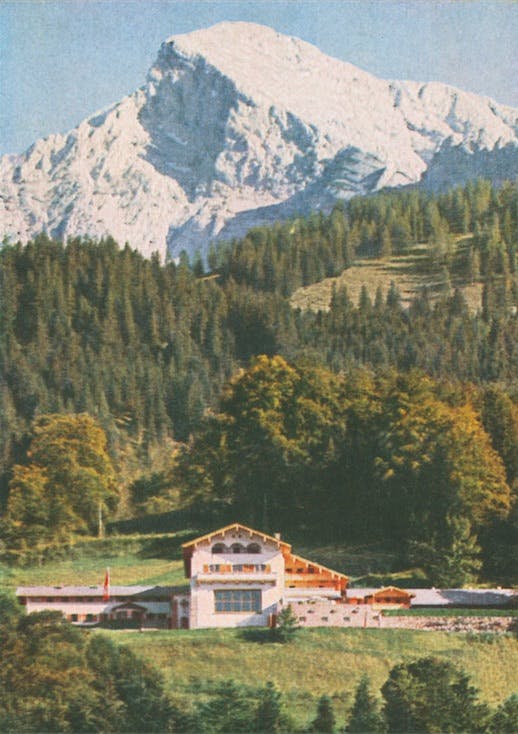

Hitler maintained three residences during the Third Reich: the Old Chancellery in Berlin, his Munich apartment, and Haus Wachenfeld (later the Berghof), his mountain home on the Obersalzberg. All three were thoroughly renovated in the mid-1930s and played a role in the creation of a new, sophisticated persona for the Führer. But it was above all his home on the Obersalzberg that became associated in the public’s mind with the private man. Here, the abundance of nature, sunlight, and the simple life, as depicted by Nazi publicists, was woven into an enchanting story about Hitler’s “true” nature and the good life he offered to Germans at the end of a long road of sacrifice and struggle. For many thousands of Germans, the Obersalzberg also became a place of pilgrimage, where one might lay eyes or even hands on Germany’s “savior.”

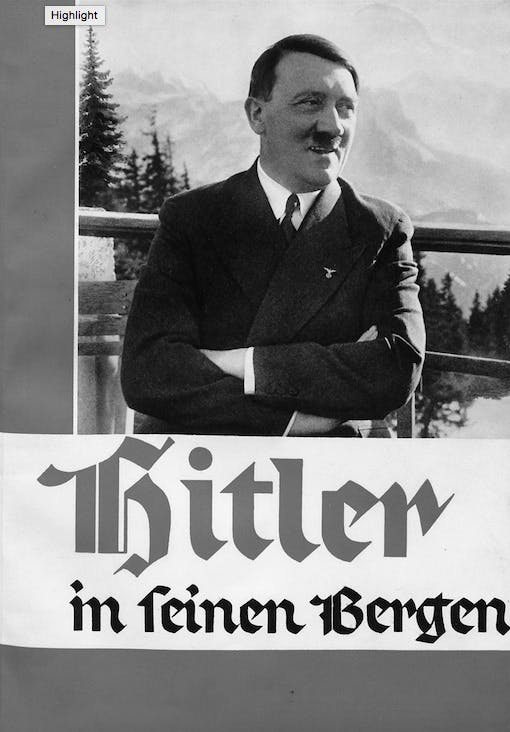

Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s photographer, published postcards and books with images of Hitler greeting enthusiastic pilgrims or conversing with his neighbors on the mountain. In this propaganda, the Obersalzberg was represented as the place that united folk and Führer. As a site of direct mediation between the German leader and his people, the Nazis argued that the mountain allowed a more “authentic” form of communication between the two than had been offered by the hated democratic institutions of the Weimar Republic. For much of the 1930s, the mainstream English-language press was complicit in perpetuating the myth of the Führer’s accessibility and neighborly relations on the mountain. What the Nazis kept hidden from the public and the foreign pressed failed to report was what was truly happening to the mountain’s inhabitants, particularly after they had outlived their usefulness as props of Nazi propaganda.

Mass pilgrimages to Haus Wachenfeld, Adolf Hitler’s mountain chalet on the Obersalzberg, began soon after he became Reich chancellor in January 1933. The phenomenon brought as many as 5000 people per day to the chancellor’s driveway, blocking nearby roads and overwhelming local businesses. If Hitler was in residence, the crowds would wait for hours, chanting, “We want to see our Führer!” In their enthusiasm, some ripped away the wooden pickets of the Führer’s fence to keep as relics.

Seeking to put more distance between himself and the boisterous onlookers and also needing space to house his guards, Hitler asked his neighbor Karl Schuster, the owner of the Türken Inn, to sell him a piece of his adjacent property. Schuster refused on the grounds of having six children to consider, but offered to let Hitler use the land for free. Despite having supported the National Socialist Party in its early years and been a member since 1930, as well as having known Hitler personally for a decade, Schuster soon learned that old loyalties meant little to the Führer when someone stood in his way.

A month after Schuster refused Hitler’s request, he found himself accused of having insulted the drunken SA and SS men who frequented his inn. The incident triggered a boycott by the Berchtesgaden chapter of the NSDAP, whose members blocked the hotel’s entrance and forced out guests and staff, leaving only the family within. When they tried to leave, they were hit by rocks and spat upon by the pilgrims waiting near Haus Wachenfeld. Ostensibly because of the threat to his safety, Karl Schuster was taken into “protective custody” and imprisoned for two weeks. Hitler, meanwhile, refused all contact with his neighbor, and as the hotel’s finances went into the red, Schuster sought out buyers. Offers evaporated, however, when local officials made clear that the hotel’s license would not be renewed.

Finally, Angela Raubal, Hitler’s sister, who lived with him at Haus Wachenfeld—and who was wholly unsympathetic to her neighbor’s plight but aggrieved by how it inconvenienced her—notified Martin Bormann, Hitler’s private secretary and manager of his Obersalzberg properties. Bormann compelled Schuster to sell him the inn and, after the family left in November 1933, transformed it into barracks for Hitler’s SS bodyguards. The Schuster family was forbidden to resettle anywhere near the Berchtesgaden region, and its adult members were compelled to sign an agreement not to speak about having been Hitler’s neighbor or about their expulsion. When Schuster did confess to his new neighbors, who were suspicious of a man who refused to talk about his past, he was again imprisoned.

Around Berchtesgaden, by contrast, talk about the family’s treatment was spreading, prompting the town’s NSDAP chapter in January 1934 to publish a notice in the local newspaper forbidding any further discussion of the Schuster case. Those who disobeyed were warned that they would be labeled enemies of the state and sent to the Dachau concentration camp. Karl Schuster, a broken man, blamed himself for his family’s ruin and died of a heart attack in 1934, at the age of 58.

The acquisition of the Türken Inn did little to staunch the Nazis’ desire for more space on the Obersalzberg to accommodate Hitler’s growing entourage as well as to conduct government business. As the regime’s machinery of oppression churned out masses of victims—some forty-five thousand Germans were held in concentration camps and unofficial torture centers in the first half of 1933 alone—the need to protect Hitler also grew more pressing1. In the years following the Schusters’ eviction, Bormann directed a radical and violent transformation of the mountain, as its original inhabitants were removed to make way for a heavily guarded enclave of the Nazi elite. If Hitler’s neighbors had thought of him as one of their own, he, clearly, did not return the sentiment.

While a few of the villagers departed voluntarily, content with the compensation they had received, many refused to go. Some had businesses that were beginning to flourish with the increased tourism. Others felt the compensation Bormann offered was grossly inadequate. And yet others simply did not want to leave their homes and farms, which had often been in the family for generations. Those who made trouble found themselves on the receiving end of Bormann’s brutal tactics. In winter, a favored method to hurry a departure was to remove the roof of a house that was still occupied—the residents tended not to last long in the freezing temperatures and deep snowfalls. In other cases, recalcitrant sellers were threatened with deportation to the Dachau concentration camp. This was no idle threat: a young photographer named Johann Brandner who dared to petition Hitler directly about the loss of his shop was sent to Dachau for two years.

By 1937, the majority of the original inhabitants had been removed and their houses demolished to improve Hitler’s views or accommodate the needs of the new elite community. Yet throughout the period of seizure and evictions, and for years afterwards, National Socialist propaganda continued to celebrate a people and way of life on the Obersalzberg that the Nazis were systematically destroying.

On April 25, 1945, as the Berghof went up in flames after having been bombed by Allied air forces, Johanna Stangassinger, a young woman, watched the fire from across the valley with her family. Still feeling the pain of forcibly losing her own home on the Obersalzberg to Martin Bormann eight years earlier, she turned to her father and said, “This is the most beautiful sight of my life, Hitler’s house burning, just as our houses have burned.”2

Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 1933-1939 (London: Lane, 2005), 81.

Ulrich Chaussy and Christoph Püschner, Nachbar Hitler: Führerkult und Heimatzerstörung am Obersalzberg, 6th ed. (Berlin: Links, 2007), 72-80, 183.

Excerpted from Hitler at Home by Despina Stratigakos. Copyright ©2015 by Despina Stratigakos. Excerpted by permission of Yale University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.