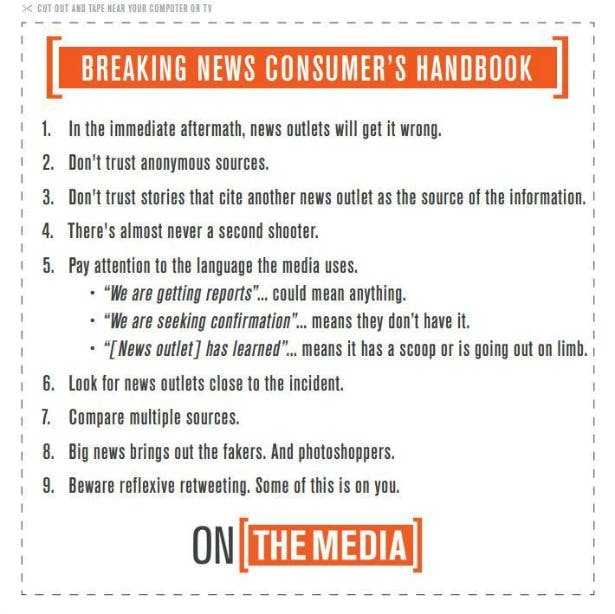

Two years ago, and a few days after Aaron Alexis killed 12 people at the Washington Navy Yard in D.C., Alex Goldman of NPR’s On the Media posted his “Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook.” His nine simple rules remain regrettably useful after a gunman killed 9 people on Thursday at Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Oregon.

I heartily endorse all these—and I have a few to add, based on 16 years covering mass shooters and making some of these mistakes.

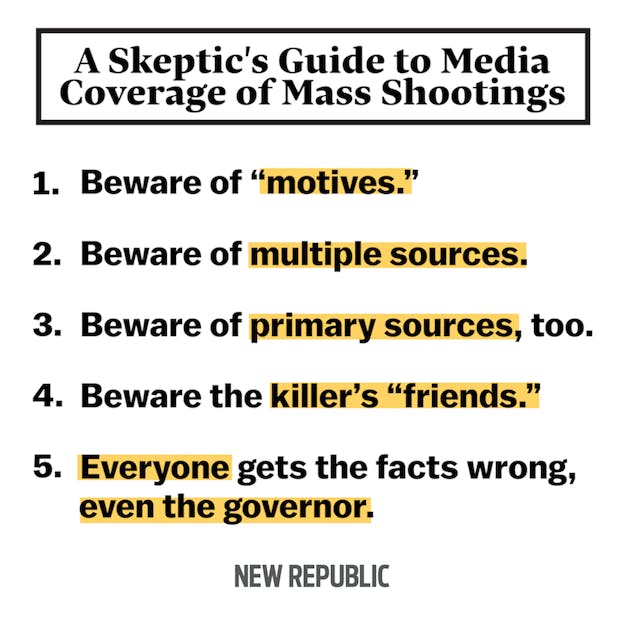

Beware of primary sources, too.

They are only primary on a limited number of facts. These witnesses may have been on campus, and even seen much of it unfold, but almost nobody sees everything. And witnesses obviously have no access to police or hospital information about fatalities. When survivors go on air in the aftermath, we're often hearing a mixture of what they saw directly and what they heard from others, often originating on TV. It's very difficult to discern what’s truly first-hand and what came through the grapevine.

I was happy to see Brooke Baldwin gently pushing back on a traumatized victim live on CNN on Thursday afternoon, when the woman began repeating all sorts of information she could not possibly have gained first-hand. The witness then explained that she was getting much of it from social media. Because this woman was part of a small-town community, she may have been good at culling through social media, knowing which sources to trust; victims tend to be well connected in their own community, especially in small towns, so their hearsay tends to be much better than the average hearsay. But it’s still hearsay.

Beware of "multiple sources."

While I was waiting to go on air at MSNBC on Thursday afternoon, a witness on the phone repeated a detail, and anchor Brian Williams noted that this was the second time they had heard that, sensing a pattern. But co-anchor Kate Snow whispered that it was the same underlying source. Good catch! It's an easy error, rarely caught that quickly, and probably not Williams's fault. How would he know, sitting in that chair, hearing witnesses brought to him by producers? It was a perceptive call, which illustrates how easily false certainty can be introduced. Reporters and anchors often have no way of knowing where the information originated. Here’s where most of it originates: Us. The media. Witnesses then circulate it back, confirming it, so we repeat it: an endless cycle of affirmation.

The most extreme example I've ever seen was the Trenchcoat Mafia at Columbine. By the morning after the attack, virtually every student was telling reporters that the killers were deeply involved in that group, which did indeed exist. Two thousand students attended Columbine, and the vast majority were out grieving in Clement Park. I heard it endlessly that morning. Nearly 2,000 primary witnesses—all of whom were wrong because they'd gotten it from TV. By afternoon, I was hearing a counter-narrative, from the very few students I could find who actually knew Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold personally. The barely perceptible second narrative barely got reported, but proved correct: the killers were friends of Trenchcoat members, on the fringe of the group at most, and it had nothing whatsoever to do with the attack.

Beware of "motives."

Already we are hearing statements attributed to the killer: the New York Post reports that he singled out Christians. Other supposed motives are sure to surface, and one or two may prove to be true. But most won’t. Killers say all sorts of things. Some taunt their victims, make fun of them. The Columbine killers taunted kids for being black, jocks, and Christians, and each of those was portrayed as a hate crime against those groups. But the killers also taunted kids for being fat and for wearing ostentatious glasses. (Eric Harris's journals are crammed with hate for every possible group.)

Resist the urge to apply motives. If the killer mentioned a characteristic of a victim, that may simply mean that he noticed it and then used it against the victim to try to inflict more pain. Nothing more.

Beware the killer's “friends.”

Tomorrow we will start hearing from friends of the killers. Be wary of how well they really knew him, and what period of his life. The first thing I look for is the age. Inevitably, major media will start trotting out friends from junior high. Authorities now say the killer was 26 years old. How similar were you between 12 years old and 26? More importantly, the vast majority of shooters have struggled with either depression or more extreme forms of mental illness such as schizophrenia. The onset of these conditions typically occurs during puberty, as the brain chemistry undergoes fundamental changes.

Some childhood information can be useful, particularly if it involves key traits like early cruelty to animals. But it hardly ever does. Treat these childhood stories as useful tiny fragments of the full picture, rarely more.

And consider that the people closest to the killer, the ones who really knew him, often run for cover. Consider how scary it is to be best friends with a mass murderer, or related to him. Sometimes people who knew him well will talk, but usually not.

Everyone gets the facts wrong, even the governor.

Most of us start trusting information when it comes from a senior source, like the chief of police. The further up the chain, the more it seems airtight. At Columbine, for instance, Jefferson County Sheriff John Stone seemed incredibly trustworthy, but turned out to be a font of misinformation, which began the first day. Nearly every newspaper in the country ran banner headlines about 25 dead the next morning, based on Stone's news conference. It turned out to be 15.

On Thursday afternoon, Governor Kate Brown conducted a brief press conference, stating the killer's age as 20. As of this posting, it's 26. And most of the networks reported for most of the afternoon that Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum had announced 13 dead, in addition to the gunman. An additional "20-plus" wounded were widely reported by authorities. By the evening, it was ten dead and seven wounded. By 11 p.m., it was still unclear whether those ten dead included the gunman. The Oregonian reported that it did, while The New York Times stated: "[Douglas County Sheriff John Hanlin] declined to say whether the gunman was included in the death toll."