There’s no surefire way to become an elite violin soloist, but there’s one thing in particular you can do to help your odds: Be born to musician parents. Even then, you’re probably screwed. For Izabela Wagner’s study Producing Excellence: The Making of Virtuosos she interviewed nearly 100 prodigies, and what she found is best put by one former soloist, “For every ten students, one will attempt suicide, one will become mentally ill, two will become alcoholics, two will slam doors and jettison the violin out the window, three will work as violinists, and perhaps one will become a soloist.” For aspiring violinists and their parents—including Wagner herself—those are not good chances. Why would anyone choose that kind of life?

A five-year-old can choose a movie or an ice cream flavor, but the verb “to choose” is a stretch when it comes to a career path. Violin virtuosos have to choose their job at various points, but none of them makes the first choice to join the profession. No toddler holds a bow of their own volition; that choice belongs to the parents. In the early years of soloist-track training, parents are the “assistants” who initiate the child into playing, find an instructor, enforce the practice regimen, provide transportation, pay training costs, and navigate professional networks on their child’s behalf. A common violin teacher’s maxim that Wagner quotes is: “I do not need prodigy pupils, only gifted mothers.”

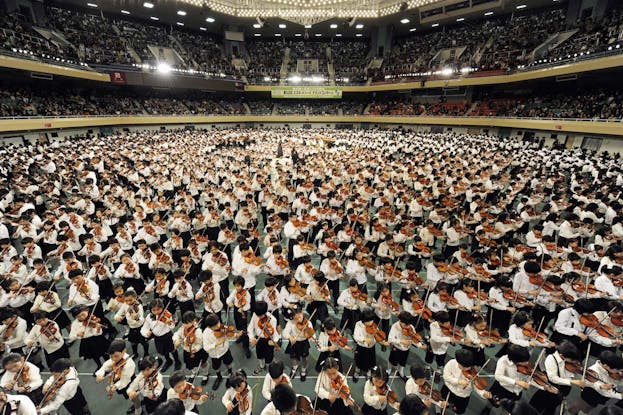

When we think about child music prodigies—among whom violinists are the most vaunted—we tend to think of a miraculous coincidence, a ray through the clouds from providence or the tumble of numbered balls in the genetic lottery. Some kids are born with special talents and with the right training and effort they can grow to play the violin very well. But virtuosos are made, not born, and as Wagner details there’s a market process for their production and distribution.

A child’s ability to successfully climb the violin ladder depends on a triad of actors: the performer him or herself, the parent, and the teacher. It’s a formulation that has been around for a hundred years, but the age at which kids begin has inched lower over time. The biographies of exceptional performers and childhood prodigies like Isaac Stern, Yehudi Menuhin, Mischa Elman, and Sarah Chang inspired a generation of parents. In Wagner’s subject group, 79 percent began their studies before the age of seven. For a young would-be soloist, the most important quality is temperament. There are more than enough potentially capable children, but the number willing to spend hours a day practicing and forsake all other pursuits is smaller.

In the early 20th century, eastern-European Jews dominated the upper ranks of the violin hierarchy. Wagner attributes their success to a number of specific cultural-historical factors (high interest in music, investment in formal education, knowledge of foreign language), not the least of which was fear of anti-Semitic violence. “The high status of conservatory students helped entire Jewish families of gifted pupils escape life in the ghetto,” Wagner writes, “enabling them to obtain permission to live in city centers where they were protected from pogroms.” The story about a talented young musician pulling his family out of the ghetto is an old one, and a child has always been the best asset some households have.

Within the practice room the teacher retains full authority and the parent is a silent partner—though many stick around to watch. Outside, parents are deputized teaching assistants as well as managers. Because the costs for lessons, equipment, and travel are so high—unfortunately, Wagner declines to survey on exact amounts—parents with music backgrounds who already know the game are more likely to pay. “In interviews, parents avoided evaluating education costs, stating that they ‘have no choice,’ and ‘aren’t entitled to refuse’ financing their child’s soloist education.” One instructor told Wagner that his less-gifted students subsidize the more talented ones, but for the most part violin is now a rich kid’s sport.

As violinists mature, they come to take on more responsibility for their careers. As teenagers they have to recommit to the soloist path, with the vast majority of them withdrawing from traditional schooling to clear time for practice and competition travel. They must maintain a teachable bearing under intense and often authoritarian pressure while also developing style and personality. They must learn to perform in front of audiences with poise and manage the disappointment that comes with losing and an intensely political system. Wagner bookends her story with a 16-year-old who, outraged at a rigged competition, goes off script and plays the piece she wants instead of the one she’s told, thereby risking her whole career. Some competition judges prefer Russians, some prefer pretty girls, and all of them prefer their own students. Playing the violin with world-class skill is just one of many challenges that soloist students face, not least of which is the common knowledge that almost every one of them will fail.

Hanging over Wagner’s project are dispiriting odds. She is a participant-observer in her own research; not only is Wagner a former musician, she is the parent of a child in violin soloist training. Although she doesn’t interrogate her own family in the text proper, with a few changes Producing Excellence could be an experimental novel about a mother who comes to realize through her research that she has made the gravest of errors. In the Appendix, Wagner allows for some self-examination:

When my position as a research worker opened the possibility for me seeing my world from a different point of view, I developed profoundly mixed emotions. It was frightening to be more fully aware of a world where competition is strong and the market is saturated. I came to realize the stakes that participants of that world—including my son—were up against… The sociologist in me was overjoyed—the mother in me panic-stricken. I tried to retreat and find ways for my son to leave this milieu and find another field of study and work. But I failed, for the bonds between him and the soloist elite were too tightly wound for his escape.

It’s a heartbreaking passage, and the scholarly product feels at that moment like poor consolation. Wagner has detailed up to his point the psychological effects immersion into the world of elite violin can have, including the erroneous belief instilled in participants that nothing else matters and anyone who doesn’t make it as a soloist is a complete failure as a person. Having subjected her son to a life of what she now knows is effectively (and effective) brainwashing, Wagner knows better. She knows that in all likelihood her son—if he’s lucky—will play violin in an orchestra and/or teach children, feeling forever second-rate. She also now knows that to an informed observer this outcome was predictable from the time her son could read.

“According to my observations,” Wagner writes, “parents in all categories [of musical experience] tend to believe that their child’s talent will enable them to prevail in the struggle that is the consequence of a saturated market.” The narrative of the child prodigy bewitches parents, and not just when it comes to music. We’re taught that the cost of genius is instability or underdevelopment in other areas, but we rarely hear about the people who finish third through tenth. Also-rans make up the vast majority in every race, but in any field of elite competition the losers have to subject themselves to the same work, same costs, same instability, same underdevelopment, but without the glory or affirmation that come with making it. We like to believe that the winners were that much better or tried that much harder, but the difference between the two is often an arbitrary twist of fate or a powerful person’s whim.

I believe glory and virtuosity are worthwhile pursuits, and a world without them would be lesser. However, for a society to cross the line from nurturing into producing excellence is to incur grave costs. Production turns raw material into waste and product, and in a competitive system both waste and product are people who, despite what they’re told, have value. It’s a myth that there’s anything parents, teachers, or kids themselves can do or be that will ensure they emerge from such a lifelong contest as wheat and not chaff. Machines that produce excellence in reality produce, principally, failure. To feed your child into the mouth of such a machine isn’t just an extreme act of faith, it’s a terrible miscalculation.