Art Spiegelman’s MAUS—an account of his father’s experience during World War II in the camps at Auschwitz and Birkenau—popularized the use of comic illustration to represent the overlap between history and memoir in the United States. In the 25 years since MAUS won a special Pulitzer prize, artists have used this hybrid comic-book form to explore global events as disparate as the Iranian revolution (Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis), the Second Intifada (Joe Sacco’s Palestine), the fall of Saigon and its aftermath (GB Tran’s Vietnamerica), and the dissolution of Yugoslavia (Sacco’s Safe Area Gorazde). In the wake of these and other works, producing a graphic novel about a historical event now serves as a way to canonize it, conferring upon it world historical status.

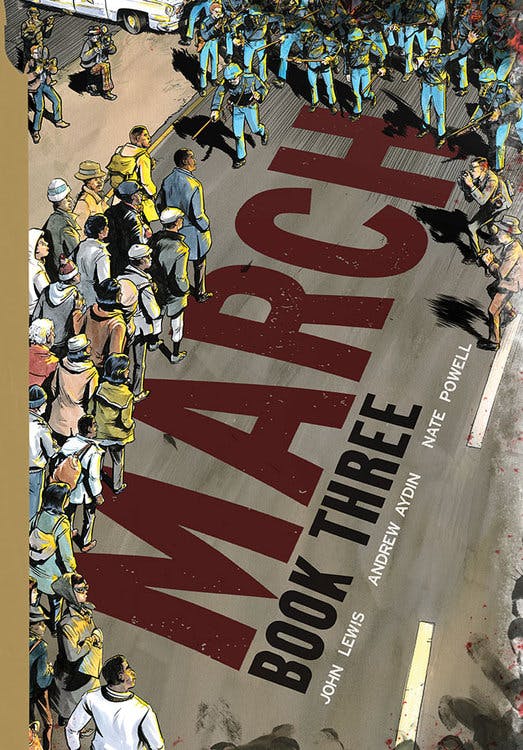

Such is the case with John Lewis’s masterful and award-winning series of graphic memoirs, March. The series was conceived during the euphoria of President Obama’s 2008 election at the urging of Andrew Aydin, Lewis’s long-serving congressional aide and an unabashed fan of comics. Lewis, who helped pioneer the sit-in as a form of protest in the United States and cofounded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), is the last of the so-called Big Six speakers from the 1963 March on Washington still living. A member of Congress since 1986, Lewis is now, at 76 years old, the most significant representative of the activist phase of the Civil Rights Movement still with us. Aydin convinced Lewis that he could reach a new, politically-engaged generation of readers if he transformed his 1999 memoir, Walking with the Wind into a graphic novel.

The undertaking has, so far, filled three volumes, the latest of which, March: Book Three was recently named a finalist for a National Book Award. The book begins with the September 15th, 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist church in Birmingham, Alabama. The bombing killed four young girls—Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Carol Denise McNair—shocking the nation and increasing pressure on organizations like SNCC and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Coalition (SCLC) to moderate their demands. Coming mere months after the triumphant March on Washington, this tragedy presaged the eventual fracturing of the movement. Still, Lewis and his collaborators in the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) and the SCLC gamely attempted to resolve the tensions between themselves and the more militant SNCC activists throughout this period.

As in the previous two volumes, President Obama’s inauguration serves as a touchstone throughout the narrative: In a flash-forward we see Lewis, exultant at the ceremony in 2009. But back in the main narrative, this glimpse of a brighter future only heightens the disenchantment Lewis feels, as he loses his place as chairman of SNCC to the more radical Stokely Carmichael. Moreover, it’s hard to see Obama’s election as the eventual payoff for all these highs and lows, given the acrimony and tragedy that has consumed Obama’s second term. During this time, we’ve seen the Republican party couch its opposition to Obama’s polices in nakedly racial terms, while we have witnessed—and continue to witness—a seemingly endless procession of black bodies shot down by police in routine encounters. In hindsight, the election of Obama has heralded not so much a break with the past as new iterations of longstanding tensions.

All this has recast the importance of Lewis’s groundbreaking early career. The uncompromising Black Lives Matter movement, which arose in response to the racialized violence of the Obama years, resembles nothing if not the early efforts of Lewis’s SNCC. The sit-ins of the 1960s have been replaced by “die-ins”; the tactics change, but the game remains the same. Suddenly, March testifies not just to the successes of an earlier social movement, but also to the continuing necessity for African Americans to assert their personhood and citizenship in a society that dehumanizes them. Lewis seems to acknowledge this, dedicating the final installment of his trilogy to “the past and future children of the movement.” A fourth volume is rumored to be in the works—one that will trace Lewis rise from Atlanta councilman to the leadership in the House of Representatives, in a much-needed, practical coda.

The sense of dread established by the opening of March: Book Three matches our fractious present, when breaking news so often alerts us to another killing. Whereas contemporary audiences now understand the Birmingham bombing as a kind of macabre turning point that galvanized the Civil Rights movement, March emphasizes that at the time there was no such certainty. Indeed, the book reminds us that segregationist whites celebrated this act of terroristic violence with more of the same, resulting in the murder of 13-year-old Virgil Lamar Ware by a group of Eagle scouts in Birmingham shortly after the bombing. Powell communicates this sense of dread through his use of shadow, and also by focusing his illustrations on the eyes of his figures. He draws on the extensive pictorial archive of the Civil Rights movement, investing seemingly familiar tableaus with a pathos that connects them to the tragedies of the present.

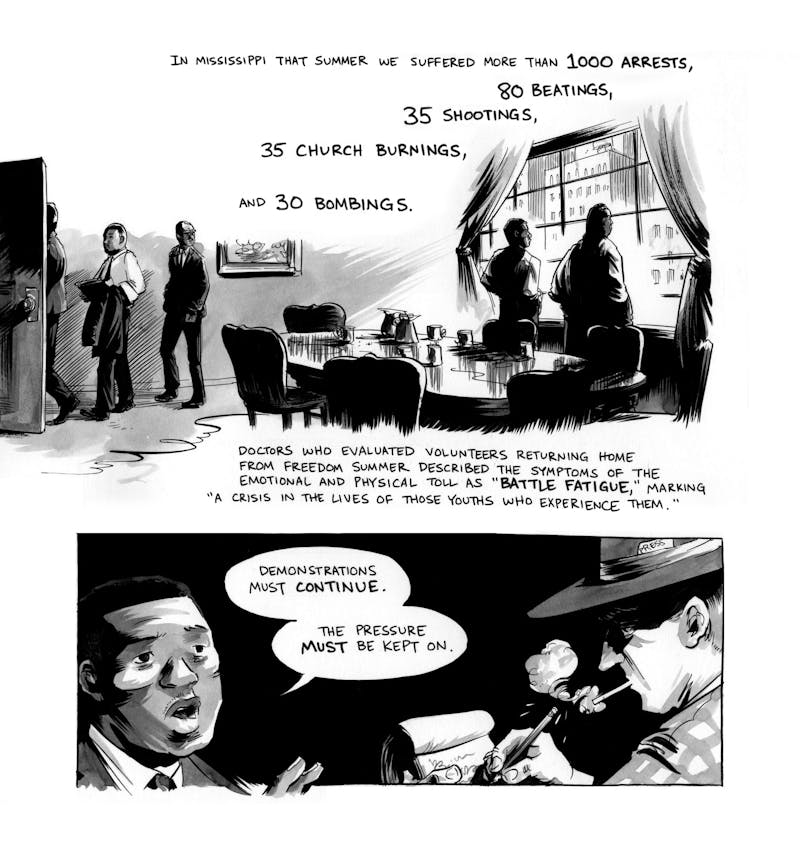

Lewis, the central character in the first two volumes of March, is often reduced to a bystander in the third, a far cry from his media anointed status as one of the “Big Six” Civil Rights leaders. As one attack follows another—the killings of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner; Bloody Sunday; the murder of Viola Liuzzo—the movement becomes more combative, its members increasingly traumatized. Lewis, however, proves slow to adapt, due to his unswerving (though some would say foolhardy) commitment to integration and nonviolence. Tensions between the leaders were exacerbated by both the participation of privileged white college students during the Freedom Summer and by a rising insistence on gender equality from within the movement, something Lewis recently acknowledged. This struggle with the shifting demands of coalitional intersectionality continues to divide groups working for progressive change to this day.

March depicts these organizational difficulties without losing its narrative thread, even as it faithfully renders the more ephemeral details of the movement. Although sound in graphic novels is usually left to the imagination of the reader, Powell excels at representing music, from the gospel of Mahalia Jackson to Martha and the Vandellas’ anthemic “Dancing in the Streets” drawing musical notes into the background to demonstrate how central certain songs were to maintaining morale. Powell’s illustrations also make clear the extent to which members of the media were implicated by their coverage of the movement, as segregationists often met them with the same aggression they turned on protestors.

The highlight of March: Book Three is Fannie Lou Hamer’s nationally televised testimony in support of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s (MFDP) attempt to displace the segregated state delegation and be seated in their place at the 1964 Democratic Convention. Shifting back and forth between Hamer’s harrowing testimony and the reactions of an increasingly incensed Lyndon B. Johnson, this scene reveals the extent to which white America resists confronting its legacy of racial oppression. Then, as now, this aversion is abetted by political exigency: Johnson, who was far ahead of Barry Goldwater in the polls, and who had already earned the enmity of segregationists by signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act, sought to mollify Southern Democrats by opposing the MFDP. This craven backsliding pleased no one, radicalizing many members of SNCC and the MFDP, and set the stage for the explosive 1968 Democratic Convention. And, as Lewis sadly notes, much of the “tragic” acrimony might have been avoided by simply writing off the former Confederacy, for although Johnson “won reelection in a landslide … he still lost the South.”

The final pages of March: Book Three depict Lewis shedding tears, alone at his home in Washington after the Obama inauguration, as he remembers Martin, Jack and Bobby and “all of the people who didn’t live to see this day.” The John Lewis of 2016, the man who recently led a sit-in inside the Capitol building, recognizes that the possibilities prefigured by that cold January day have not yet come to pass. We seem to have retreated from the promise of 2008, from the nation that so many in the 1960s sacrificed to bring into being. But March distinguishes itself precisely because it brings those people and their sacrifices back to us, returns us to Hamer and Baker and Moses and Carmichael and all the rest—and especially the youthful John Lewis, so small and so resolute. Those lives matter, not simply because of the changes wrought then, but because we still have so much to do now.