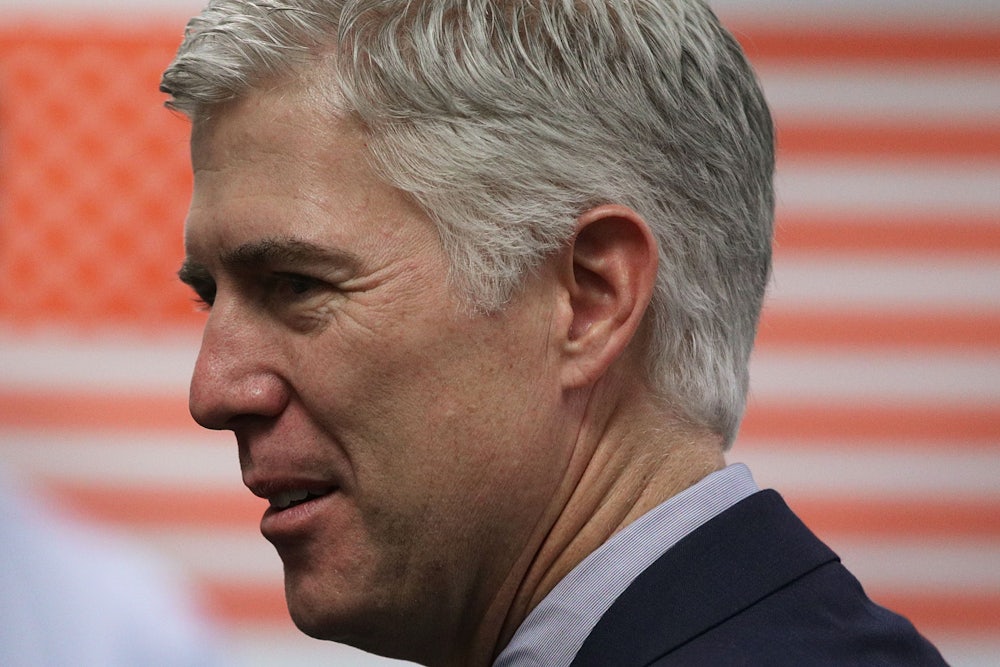

Conservatives have championed Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch

as an originalist in the mold of his mentor, the late Justice Antonin Scalia. “Judge

Gorsuch is a longstanding proponent of the view that the Constitution must be

interpreted according to its text as it was understood by those with authority

to enact it,” explained

Michael McConnell, who served with Gorsuch on the Tenth Circuit Court of

Appeals. By nominating him, “President Trump may have done more for originalism

than any President since Ronald Reagan,” wrote

John O. McGinnis, a constitutional law professor at Northwestern University,

adding that originalism “holds the most promise for maintaining a beneficent

Constitution and a constrained judiciary.”

Not since the failed nomination of Judge Robert Bork in 1987 has a nominee been advanced because of his commitment to originalism. Clarence Thomas was celebrated not for his judicial philosophy, but for pulling himself up from his bootstraps, making it all the way from Pin Point, Georgia, to the Supreme Court. John Roberts and Samuel Alito were hailed by supporters as stellar conservative jurists who had served with distinction on the federal bench. But Gorsuch, whose Senate confirmation hearings begin Monday, has been acclaimed because of his self-professed originalism. The problem is that Gorsuch’s record, reflected in his many opinions and non-judicial writings, suggests that he is a selective originalist, committed to following only some of the Constitution’s text and history—and, most damningly, ignoring the vital Reconstruction Amendments enacted after the Civil War.

There is nothing about originalism that necessitates conservatism. The problem is that many conservative originalists don’t view the Constitution in its entirety, giving short shrift to the Amendments added to the Constitution in the last two centuries that have made our nation’s charter more democratic, more equal, more just, and more inclusive. But an originalist judge cannot pick and choose among parts of the Constitution. Originalism requires fidelity to the entire Constitution, including the Amendments that make equality for all a central constitutional value, protect the right to vote as the linchpin of our democracy, and ensure that states respect substantive fundamental rights, such as the right to marry, which are not mentioned in the Constitution but are core aspects of liberty.

This is where Gorsuch falters.

Judge Gorsuch is a prolific writer, who quite often writes alone on judicial panels to express his views about a case, and he has often invoked arguments made by James Madison and Alexander Hamilton during the debates over the ratification of the Constitution. Notably, he has written a handful of opinions interpreting the Fourth Amendment’s ban on unreasonable searches and seizures, which properly recognize that the job of a judge is to enforce the amendment’s limit on abuse of power “whatever our current intuitions or preferences might be.” But Gorsuch’s embrace of originalism stops at the Founding.

His opinions concerning America’s Second Founding—the amendments adopted in the wake of the Civil War to erase the stain of slavery from the Constitution, ensure Lincoln’s promised “new birth of freedom,” and reconstruct the nation on the basis of liberty and equality for all—stand in stark contrast. Gorsuch has written opinions in four key areas of Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence: the protection of substantive fundamental rights; equal protection; fundamental fairness due to those accused of a crime; and the power of Congress to help realize the amendment’s guarantees of liberty and equality. In each of these, Gorsuch has never championed the Framers of that amendment who ensured that no government—whether federal, state, or local—infringed on basic rights, wrote equality into the Constitution, and armed Congress with the power to help realize these crucial constitutional guarantees. In fact, Gorsuch has never written any opinions based on the Fourteenth Amendment’s text and history. This is a gaping hole for a self-described originalist judge.

His opinions, more often than not, take a narrow view of the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantees and an outsize view of the respect due to the states—even though the whole point of the Fourteenth Amendment was to impose limits on the states and ensure that they respected the liberty, dignity, and equality of all. Gorsuch has written opinions that would make it harder for victims of police misconduct to go to federal court to redress abuse of power; he has voted to permit state governments to defund Planned Parenthood based on the flimsiest of rationales; and he has repeatedly dissented when his colleagues on the court of appeals held that criminal defendants had been denied the effective assistance of counsel, one of the most important constitutional guarantees of fundamental fairness. In these cases, he’s been more concerned with the treatment of states, insisting on the need for “respect for comity and federalism” and criticizing his fellow judges for failing to heed “the sort of comity” due the “States and their elected representatives” and permitting “significant new federal intrusion into state judicial functions.” In Gorsuch’s opinions, protection of basic rights often takes a back seat to federalism.

His non-judicial writings share the same basic approach. Writing in National Review in 2005, Gorsuch castigated civil rights lawyers seeking to strike down discriminatory marriage laws that denied same-sex couples the right to marry for using the courts “as the primary means of effecting their social agenda,” turning a blind eye to the Constitution’s promise of access to the courts as well as its guarantee of rights so fundamental that they cannot properly be subject to the whims of the political process.

Gorsuch’s 2006 book, The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia, examined law, history, moral philosophy, and social science, but never once discussed the text and history of the Fourteenth Amendment and its Framers’ design of protecting a broad range of substantive fundamental rights—both those in the Bill of Rights as well as others not enumerated in the Constitution—from state infringement. He took a dim view of leading Supreme Court precedents on the subject—including the 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which reaffirmed protection for a woman’s right to choose abortion—suggesting that its discussion of personal liberty and autonomy could be disregarded as dicta.

But Casey’s discussion of personal autonomy in a context key to equal citizenship—basic reproductive freedom—is an important part of the liberty the law affords to all. The basic reasoning that Gorsuch would shelve is also the core of the celebrated 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, which declared that, under the Fourteenth Amendment, gay men and lesbians possess a fundamental right to marry the person of their choice, based both on principles of substantive liberty and equality under the law. Gorsuch’s writings suggest he would be hostile to enforcing those principles.

When Judge Gorsuch appears to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee this week, he will have a heavy burden to meet: he cannot simply call himself an originalist. Instead, he must demonstrate that he truly is one—and that his brand of originalism respects the whole Constitution, and that he will follow it wherever it leads. He must demonstrate his fidelity to the Second Founding Amendments that protect fundamental rights and ensure equal dignity under the law for all persons. And if he doesn’t, senators on the Judiciary Committee ought to ask him why.