Picture our world seen from the air. A condo tower appears as a dollhouse, each window offering a glimpse into an individual life. The street below is a flat plane, occupied by toy cars. Or a single stand of evergreens points toward the sky in the midst of a barren, snow-covered landscape no vehicle has crossed.

For most of human history, such views have been impossible for pedestrians to achieve. But in recent years, that has begun to change. Drone photography, developed by the military to enable pilots to stay on the ground while sending their cameras into the sky, is no longer limited to surveillance and warfare. Consumer drones are now available for as little as $30, and anyone with a few practice flights under their belt can take photos and video from the sky. Amateur photographers have begun to record intimate moments from the air, the way they might have once used Polaroids or digital SLRs. By 2020, according to the Federal Aviation Administration, there will be as many as 7.5 million drones operating in the United States alone; on Instagram, the hashtag #dronestagram—the format’s nickname—has attracted more than 780,000 posts.

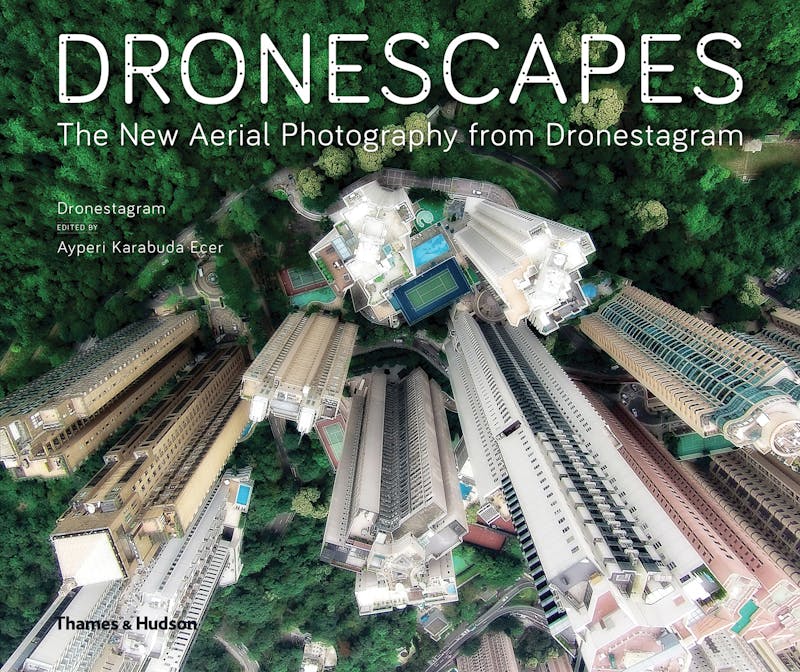

This soaring aesthetic is on display in Dronescapes, a new book of drone photography sourced from the #dronestagram community and curated by Ayperi Karabuda Ecer, formerly a photo editor at Magnum and Reuters. The imagery she has gathered represents a kind of twenty-first-century sublime, with all of the beauty drones reveal and none of the terror. Much of the collection is coffee-table kitsch: tiny swimmers bobbing in turquoise tropical waters; an Umbrian walled city enveloped in fog; a parking lot packed with cars that form a geometric zigzag; an entire chapter of wacky stunt wedding photos. The images share a certain transcendent quality; precipitous height, rather than color or composition, is their strength.

In many individual images, the shift in perspective acts as little more than a gimmick. But seen as a genre, the drone’s-eye view presents a troubling contradiction. On the one hand, commercial drones promise a newly democratized view of the world: Just as Polaroid cameras made spontaneous, roving photography easier in the 1970s, drones now give more people than ever the ability to make aerial images, to see themselves and their surroundings from a godlike vantage. On the other, that same view enables drone operators to surveil anyone or anything, without any legal process or even a clear motivation. However trivial or striking the resulting imagery may appear, the form itself requires a reckoning, since to contemplate the dronestagram is to witness both the grandeur and vulnerability of life on the ground.

There are, of course, precedents for documenting the world from above. The first aerial photograph was taken in 1858 by a French photographer and polymath named Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, who went by the pseudonym Nadar. Floating in a hot-air balloon over Petit-Bicêtre, a village near Paris, he captured a bucolic scene from the sky and brought it down to earth in the form of a permanent print. “One can distinguish perfectly on the road a tapestry maker whose cart stopped before the balloon,” he recalled in his memoir, “and on the tiles of the roofs the two white doves that had just landed there.”

The past decade has seen a comparable revolution in aerial imaging. Whereas the vast flyover shots of the past required expensive air travel, drones are both readily available and completely interactive. Drones can also fly lower and maneuver more tightly than any airplane or balloon, enabling the aerial equivalent of street photography. The rise of the drone has even birthed a new genre of portraiture: the “dronie,” which Ecer describes as “the aerial equivalent of the selfie.” These snapshots tend to demonstrate their subjects’ dominance over the natural landscape: a couple cuddling on a rug laid in a vast field, a silhouetted figure standing on top of a mountain, a human tower rising off the beach. The drone’s height means that the images can encompass more background than those from a smartphone, but people are still the focus.

Amateur drone photography has already developed a distinctive set of subjects. The book is organized into sections such as “Urban,” with photos of city landmarks and street layouts; “Fauna,” with Planet Earth–style shots of animals; and “Probe,” which documents environmental threats like pollution and wildfires. The themes are decidedly unsubtle: The photographers are preoccupied with capturing a novel view of a familiar scene, or playing tricks with the camera’s height rather than using it to push the boundaries of symbolism or the format of the photo. Superficial content dominates form. Given the camera’s distance, the results also tend to be visually static, and even alienating to viewers.

The images in Dronescapes suffer from a shortage of individuality or original style. Photographers are often identified only by their online usernames (“postandfly” or “mountaindrone”), lending a curious anonymity to the enterprise. Beyond the dronestagrams that look like stock imagery for motivational posters, the book’s best moments—such as contributor JackFreer’s eerie shot of a nuclear testing site—bring to mind the work of Edward Burtynsky, a Canadian photographer who has documented from the air the rusting hulls of disused ships, highway overpasses, and suburban sprawl. His focus is humanity’s industrialization of the natural landscape, his aesthetic an ordered ugliness that reveals the unintended consequences of such environmental intervention.

Most of the images in Dronescapes, by contrast, fail to unsettle the viewer. Since the early twenty-first century, we’ve become accustomed to the grandeur of an aerial perspective, whether from film flyovers in blockbuster movies like Skyfall, or from the daily experience of scrolling through Google Earth. Viewing the world from above has become an unremarkable experience that entails little risk or danger. Consumer drones simply allow people to create this imagery for themselves, zooming in on the specific target of their surveillance. Drone kitsch—the growing vernacular of images taken with these machines, neither inspiring nor provocative—allows us to become accustomed to being surveilled from the sky without questioning the nature of or justification for the surveillance. Since hobbyist photographers use the technology to document their vacations, Dronescapes implies, it can’t be all that bad.

If drone photography often feels glib, it may be because pictures taken from the air don’t fit easily into clear, human-scale narratives. In fact, the looming presence of the machines threatens the order of life on the ground. In 2013, the novelist and photographer Teju Cole published a series of tweets composing “seven short stories about drones.” Cole inserted the machines into the beginnings of novels by Melville, Kafka, and Chinua Achebe, giving familiar stories abrupt endings, echoing the innocent lives that drones cut off in the real world: “Call me Ishmael. I was a young man of military age. I was immolated at my wedding. My parents are inconsolable.”

Just as military drones make it “impossible to die as one kills,” as the French scholar Grégoire Chamayou observes in A Theory of the Drone, the drone photographer can see without being seen—a clear advantage in warfare and law enforcement alike. Drones first established their role on the battlefield in the 1980s, and by 2002 the CIA was successfully using Predator drones in targeted killings. One recent tabloid story told of a husband who caught his cheating wife with footage from a drone; a New Mexico court ruling justified police using drones to surveil citizens under the strange logic that the machines are less obtrusive than helicopters.

The romantic imagery collected in Dronescapes doesn’t reflect the decidedly unpretty purposes to which most drones are put. This is a deliberate choice: The book is presented in part as a document of drone photography’s early flourishing, before, as its editors foresee, government regulation limits the use of aerial imaging to armies and spy agencies. The editorial tone seems to admonish readers for their undue anxiety over drones. “The Wild West of drone photography is slowly diminishing,” Ecer writes. “The fear of terrorist attacks, of paparazzi invading the sky and drones crashing into aeroplanes are just a few examples that have led to new jurisdictions to restrict their use.”

Yet other artists have tried to grapple with the political implications of using drones as imaging technology. From 2012 to 2015, the British artist and writer James Bridle ran an Instagram account, also called “Dronestagram,” which posted satellite photographs of locations bombed by military drones in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia. The juxtaposition of desert landscapes with the names of victims and the dates of their deaths presents an aesthetic utterly unlike the grand and peaceful vistas of much drone photography. The project was chilling because it made visible the work of often-invisible machines, approximating what military drones and their pilots actually see when they are deployed.

The most powerful drone imagery is not aspirational snapshot photography, but documentary. Last November, at the height of the protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline, an aerial drone captured scenes of police blasting protesters with water cannons. Men and women scatter like ants across the floodlit landscape as the drone weaves nimbly in and out of the water, conveying the violence and unpredictability of the assault. Civilian drones also captured the austere geometry of the pipeline being constructed under cover of night, and the ominous sight of armored police vehicles surrounding the clutch of tents and tepees erected by protesters.

The drone footage quickly went viral, netting hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube and instantly becoming an iconic image of the ongoing protests. So many activists and journalists were using drones to document the protests, in fact, that the Federal Aviation Administration instituted a no-fly zone in the area. The message was clear: Drones are fine for bombing terrorists or observing suspects, but they are far too dangerous when placed in the hands of ordinary citizens.

As the protest imagery suggests, drone photography at its best can provide us with a more expansive and revealing view of the world around us. Not only do drones empower users to document their own unique views, they also challenge the perspectives presented by larger and better-equipped institutions. This newfound visual authority can be used to disrupt authority itself—but only if we spend more of our time examining the nature of power than looking at ourselves.