In

2009, when Alice Methfessel died in California at age 66, everything in her

house was rifled through and catalogued. That’s because Methfessel had once

been the lover of the poet Elizabeth Bishop—the woman to whom Bishop dedicated

the National Book Award-winning Geography

III. When “a mass of unidentified paper

sitting in a storage container” was discovered among Methfessel’s effects in

2010, her heirs “promptly sold the lot to Vassar,” in the words of Bishop

scholar Lorrie Goldensohn.

The discovery of letters at Methfessel’s ranch property was not the first time that Bishop’s private writing has been found and published since her death in 1979. It’s an exposure that the poet would not have welcomed: Bishop was a private person during her lifetime, and deliberately withheld her personal life from her published poems. The decision to publish after her death the poems that Bishop had kept private in life has sparked controversy. In 2006, Alice Quinn of the New Yorker edited a collection of Bishop’s unpublished work, which Helen Vendler lambasted in this publication. “Had Bishop been asked whether her repudiated poems, and some drafts and fragments, should be published after her death,” Vendler wrote, “she would have replied, I believe, with a horrified ‘No.’”

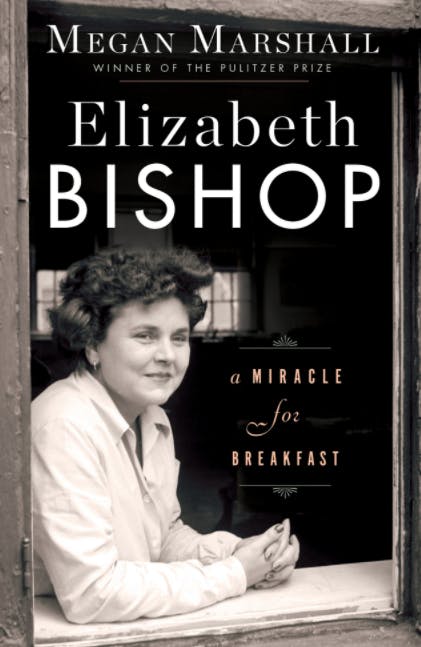

It is this latest reserve of material from Methfessel’s house that Megan Marshall includes in her new biography of Bishop, Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast. It is not new information that Bishop loved and lived with multiple women over her 68 years; Bishop’s first biographer, Brett C. Millier, confirmed the partnership with Methfessel in 1993. Nor are the traumas that punctuated Bishop’s life revelations to anyone who has read about her before: Her childhood abuse and alcoholism are well known to her devotees. What Marshall’s revisit offers is an attempt to connect more fully than ever Bishop’s poetics with the facts of her personal life—a synthesis of life and work that becomes a beguiling prospect when its subject is the famously private Bishop.

Though readers, critics, and especially biographers have long romanticized the discovery of caches of personal effects in the homes of writers, the ins-and-outs of their unearthing are decidedly unglamorous. They can verge on intrusive, tasteless, and even criminal in some cases. When Italian journalist Claudio Gatti revealed the identity of novelist Elena Ferrante in 2016, incensed fans wrote of Ferrante’s anonymity as a feminist act of resistance against the state of modern authorship, in which the writer is increasingly asked to reveal herself: physically, with an author photo, as well as biographically, in pages and pages of “behind the book” pieces, personal essays, appearances, panels, and social media accounts. For a poet like Bishop, whose work was so often predicated upon withholding, these demands can seem particularly violating—not least because they are made most passionately and persistently of authors who are women.

Bishop’s body of work is notoriously compact. She published only 100 poems in her lifetime. Octavio Paz said of Bishop that her poetry is a lesson in “the enormous power of reticence.” She won a Pulitzer Prize, two Guggenheim Fellowships, and a National Book Award for poems that were modern in style but removed in register, as devoid of biographical detail as they are short in word count. “Something needn’t be large to be good” is how her mentor and friend Marianne Moore described the Bishop aesthetic. Bishop herself called it her “Scotch-Canadian-Protestant-Puritan” temperament.

Bishop’s enduring popularity is all the more remarkable, then, given how different she was from her contemporaries, and from the confessional direction American letters has trended since. Bishop was holding herself back from her work at a time when it had never been less fashionable to do so—friends like Mary McCarthy, who wrote The Group about their shared social circle at Vassar College, were mining their personal lives to great acclaim when Bishop was struggling to finish just one poem a year. So how can we arrive at an understanding of the power of her poetry through the dissection of her ephemera, through the piles of papers and self-reflections that she deliberately kept out of her published work? The answer is that we can’t—or at least that the point reached is one in which Bishop herself continues to evade capture. Instead, Marshall’s biography tells us about what the current market demands of women writers, and the origins of this impulse for more, more, more.

Bishop was born in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1911, but she was raised partly in Nova Scotia, the first in a series of displacements that would inform her roaming adult life. Her father died when she was an infant, her mother was institutionalized soon after, and Bishop was a sickly child, raised by her grandparents. Her aunts, Maud and Grace, were kind to her when she eventually moved in with them in suburban Boston—her Aunt Grace once drew a diagram of her ovaries and uterus in the bathroom rug, to comfort her after getting her first period. But Bishop was terrifyingly alone. Her Uncle George touched her in the bathtub, and once dangled her over the railing of a staircase by her hair.

Eventually she went to Vassar, where she met the poets whose intellects would shape her own. It was there that she was introduced to modernist pioneer Marianne Moore, who became a personal hero. Moore “goes right on producing perhaps one poem a year and a couple of reviews that are perfect in their way,” Bishop admired. That a woman poet was writing not out of sentimentality but observation was thrilling too. She moved to New York; Moore lived in Brooklyn.

Bishop wrote slowly and haltingly. She travelled constantly to avoid the fact that she had no family home. But the work that did find its way into the world in these early years established her singular voice and experimentation with form: “A Miracle for Breakfast,” Bishop’s debut in Poetry magazine, is a meditative sestina, with repeated end words that gave the “miracle” event—a women selling Wonder bread door to door during the Depression—a religious quality. Another was “The Fish,” published in The Partisan Review in 1940, around the time Bishop and her first long term partner, Louise Crane, split up. The simple but strong ending turn of the poem— “And I let the fish go”—jars with an unpublished verse from the same time, a whining, self-pitying note regarding Louise’s infidelity. “See here, my distant dear, I lie/Upon my hard, hard bed and sigh/For someone far away, Who never thinks of me at all.” There’s a sharp and deliberate difference between these two lines; the one Bishop chose to show the world, and the one she did not.

In 1946, as World War II ended, Bishop was living in Key West, and had finally found a major publisher in Houghton Mifflin, who would put out her first collection, North and South. Success and recognition would follow. But demons lurked in spite of this success, and one was the pressure to work, to make appearances befitting her accolades and hobnob with poetry crowds in New York and Washington. She was already sick of “Poetry as Big Business,” she wrote. And these professional concerns seemed always to manifest physically: in asthma attacks, and in her heavy drinking, which had begun in college. The whining voice from that poem to Louise Crane reads like a drunken one, especially when you know how often Louise and other lovers had to pick her up from a fall, or put Bishop to bed. In her private correspondence, Bishop connected this dark streak to her relationships and to the tragedies in her life, how the ground always seemed to be shifting underneath her.

“I am one poet who’s going to stay sane till the bitter end,” Bishop wrote in 1966, after hearing that her friend, the poet Randell Jarrell, had committed suicide by walking into oncoming traffic. Maybe she could sense that elements of her own life were again wobbling around, like signs of an impending earthquake. She had been living in Brazil for more than a decade, after a 1951 trip to Rio turned into a long term partnership with the modernist designer Lota de Macedo Soares, who was building a glass house in the shape of a butterfly when Elizabeth met her. For many years, life in Brazil with Lota was as stable as it had ever been for Bishop. She finally finished her second book due to Houghton Mifflin, A Cold Spring, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1956. Her new environment in the lush hills of Ouro Preto and the favelas of Rio produced “Manuelzinho” and “Squatter’s Children,” among other poems. But Lota was unstable and temperamental; she was obsessed with her work, and Bishop distracted herself with other women. Lota had fallen into a prolonged delusional state by 1967, when Elizabeth travelled back to Greenwich Village to try and get some air. Lota insisted on following soon after, but she didn’t last a day: She took twelve Valium in the middle of the night, and died a week later. The lines that Bishop wrote in the aftermath are devastating: “No coffee can wwake you no coffee can wakeyou no coffee / can wake you / No coffee.”

Another major figure in Bishop’s life had been in and out of hospitalization during these decades. Robert Lowell, “Cal” to Bishop, had been introduced by Randall Jarrell, became a longtime friend and confidant. Lowell had accepted a teaching position at the University of Essex, and Bishop was to fill in for him at Harvard in 1970. Harvard is where she would eventually meet Alice Methfessel, and produce some of her most beloved work, as well as where her life would fleetingly intersect with her biographer Marshall’s.

Lowell was perhaps the most notorious practitioner of the confessional poetry Bishop repudiated, along with contemporaries like Sylvia Plath, Ann Sexton and John Berryman. Lowell’s mining of his private life for his public poetry jeopardized his friendship with Bishop in 1973 with his publication of The Dolphin, in which he quoted from the anguished letters of his second wife, the writer Elizabeth Hardwick. He had even doctored some of Hardwick’s words, which Bishop had found unforgivable. “When you wrote Life Studies perhaps it was a necessary movement, and it helped make poetry more real, fresh and immediate,” she wrote to him. “[But now], anything goes … it’s cruel.”

“You just wish they’d keep some of these things to themselves,” Bishop complained of those members of what she called “The School of Anguish.” For Bishop, much of this frustration was directed at how the confessional, for a woman, meant hemming herself in, when poetry had always freed her. In the 1970s, when Adrienne Rich and others lobbied to include her in anthologies of woman poets, she bristled. She maintained that men and women “do not write differently … I don’t like things compartmentalized like that … I like black & white, yellow & red, young & old, rich and poor, and male & female, all mixed up.” Some would call this internalized misogyny. But her poetics offer an alternate interpretation of this aversion: She sought to tap into “the surrealism of everyday life, unexpected moments of empathy” in order to produce something universal, whole. She had felt most of her life that she was at odds with the world around her, and that poetry was her salve. Verse could break into the essential, crack open “the horrible and terrible world,” which had given her such pain. Why bring reality back in?

Marshall’s characterization of the difference between Lowell’s and Bishop’s poetry is that, for Bishop, “keeping secrets made her poems tell more than outright confessions,” as if the details behind her poetry fought against her to reveal themselves. Instead, her most beloved poem, “One Art,” written about the blue-eyed Alice Methfessel, demonstrates how deliberate Bishop’s choices were, how the balance between the universal and the personal is painstakingly wrought. There is a frantic anguish in the poem’s famous parenthetical —“(Write it!)”—but the feeling is heightened, not diminished, by its place within the formal bounds of the villanelle rhyme scheme.

Perhaps this delicate balance that Bishop achieved in her work is why the power of the poetry fades inside Marshall’s chronicling, so concerned it is with finding autobiography in Bishop’s poems. And where it can’t be found, it is amplified by the author’s own confessions from her time at Harvard: She was a student of Bishop’s for one semester. The narrative that Marshall is looking for in Bishop’s life is wholly too neat and sweet, and eclipses the real struggles of her subject: a writer who was not at home in the world, not comfortable with exposing herself, but who still created work of arresting beauty.

“Art just isn’t worth that much,” Bishop once wrote to her confessional friend Robert Lowell. Her use of “worth” should be marked here as a financial one; for women writers especially, the personal can be regarded as a vessel of truth or authenticity, but it is in many ways another method of turning art into something sellable. We should understand Bishop’s turn to privacy in this context. Her work endures because it defies contemporary urges to produce more and more material. Just as Alice Methfessel sold her papers to the archive at Vassar in 1998, and her heirs sold the ones she had kept in 2010, Bishop might have sold herself if she had written more of herself into her work. But she didn’t.