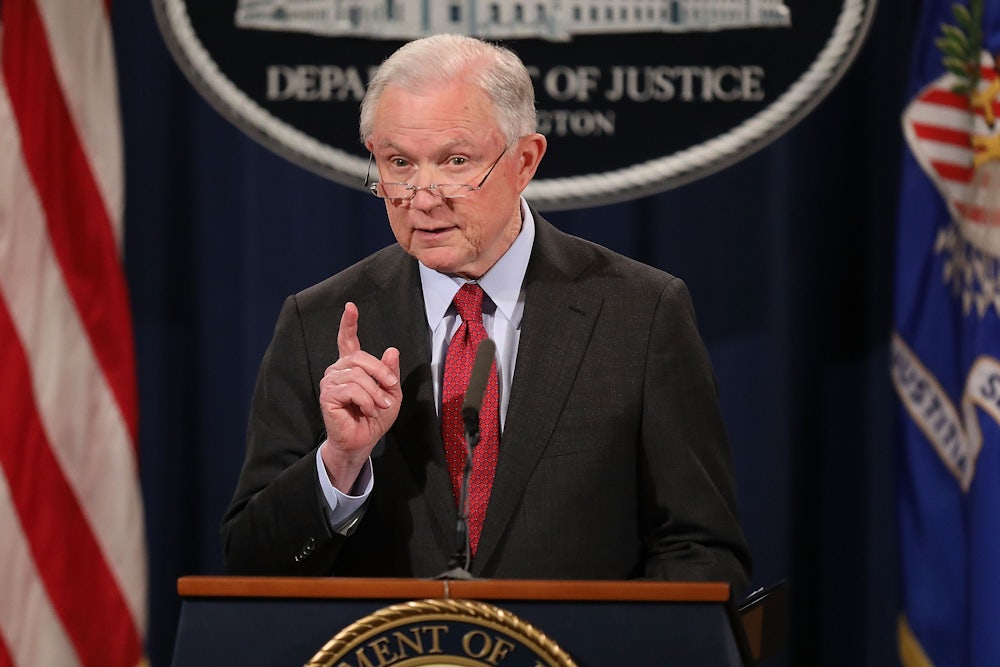

Jeff Sessions, the United States attorney general, speaks often of his deep religious faith and regularly attends the White House Bible study group. So it is little surprise that he would quote the holy book to defend himself from criticism over the Trump administration’s policy of separating migrant families at the border and detaining the children in massive warehouses.

“I would cite you to the Apostle Paul and his clear and wise command in Romans 13, to obey the laws of the government because God has ordained the government for his purposes,” Sessions told law enforcement officers in Indiana, an argument he’s been making since at least 2016. “Orderly and lawful processes are good in themselves. Consistent and fair application of the law is in itself a good and moral thing, and that protects the weak and protects the lawful.”

Asked to explain Sessions’s comments and the morality of the administration’s policy, Sarah Huckabee Sanders told CNN’s Jim Acosta, “It is very biblical to enforce the law, that is actually repeated a number of times throughout the Bible.” If biblical scholars ran their own Politifact, they’d rate Sanders’s claim “partially true.” Sessions has put forward a selective reading of Romans 13; the chapter also contains passages that undermine the very policy he’s trying to defend. “Let no debt remain outstanding, except the continuing debt to love one another, for whoever loves others has fulfilled the law,” the Apostle Paul wrote to this disciples.

But exegesis belongs to the realm of theologians. Sessions’s comments are troublesome not because they misrepresent the Bible or constitute a needlessly religious justification for a secular policy, but because they echo some of the darkest chapters in American history.

As Christian historian John Fea told The Washington Post on Thursday, American southerners frequently cited Romans 13 in defense of the institution of slavery. “[I]n the 1840s and 1850s, when Romans 13 is invoked by defenders of the South or defenders of slavery to ward off abolitionists who believed that slavery is wrong,” he said. “I mean, this is the same argument that Southern slaveholders and the advocates of a Southern way of life made.” Slavery was legal, after all; to question Southern law was to question God.

In fact, early debates over the morality of slavery frequently played out in churches, a practice that continued as war broke out. Abolitionists had no difficulty defending the morality of their position, given the horrors of chattel slavery. Confederates, meanwhile, took up the language of a shared faith and deployed it in the service of propaganda.

The Confederacy’s desire for divine approval shines clearest in the writings of R.L. Dabney, a Confederate chaplain and Presbyterian minister who committed himself to drafting Christian defenses of Southern slavery. His 1867 polemic, In Defense of Virginia and the South, lays out his case that “in the Church, abolitionism lives, and is more rampant and mischievous than ever, as infidelity; for this is its true nature. Therefore the faithful servants of the Lord Jesus Christ dare not cease to oppose and unmask it. And in the State, abolitionism still lives in its full activity, as Jacobinism; a fell spirit which is the destroyer of every hope of just government and Christian order.” Dabney has been dead for 120 years, but his beliefs survive. He’s beloved by kinists, who “assert that the Bible condones segregation of the races,” according to the Anti-Defamation League. The website of the Association of Classical Christian Schools still recommends Dabney’s work On Secular Education; the association’s founder, far-right Calvinist minister Douglas Wilson, has extensively praised the Confederate chaplain’s thought.

The Bible has been used to justify the oppression of other non-white people in America. As Mother Jones noted in 2017, the U.S. government established a network of boarding schools to handle its “Indian problem” in the late nineteenth century. These schools—which were often explicitly Christian—split up families in a deliberate bid to sever Native children from their tribes and from their culture. “Kill the Indian and save the man,” as Carlisle Indian School founder Richard Pratt once declared.

Christianizing Native children was considered akin to Americanizing them, the goal being to root out every last vestige of Native identity. The federal government delegated much of this project to the clergy, as an archived copy of an 1885 report from the Board of Indian Commissioners reveals. To commissioners, “mission schools,” or Christian boarding schools, proved that “Indians can learn.” They boasted that children, once kidnapped from their families and tribes, rarely returned to their pagan ways. Of Natives themselves, commissioners wrote, “We should misjudge him if we deemed him so religiously inclined that he spent his days unoccupied in the open air on purpose that he might with untutored mind ‘see God in the storm, or hear him in the wind.’”

Mission schools traumatized generations of Native children, making their legacy especially relevant in the context of Sessions’s remarks: The American government has separated families before, and officials previously took up Christianity to justify the practice. Now, the government is turning to Christianity again to justify their traumatization of a new generation of brown-skinned children. That these refugees are mostly Christians appears not to matter to Sessions and his ilk; Christianity is no source for solidarity here. These Trump officials have weaponized their religious beliefs, and by doing so they’ve demonstrated again that this administration is not an anomaly. It’s thoroughly American.