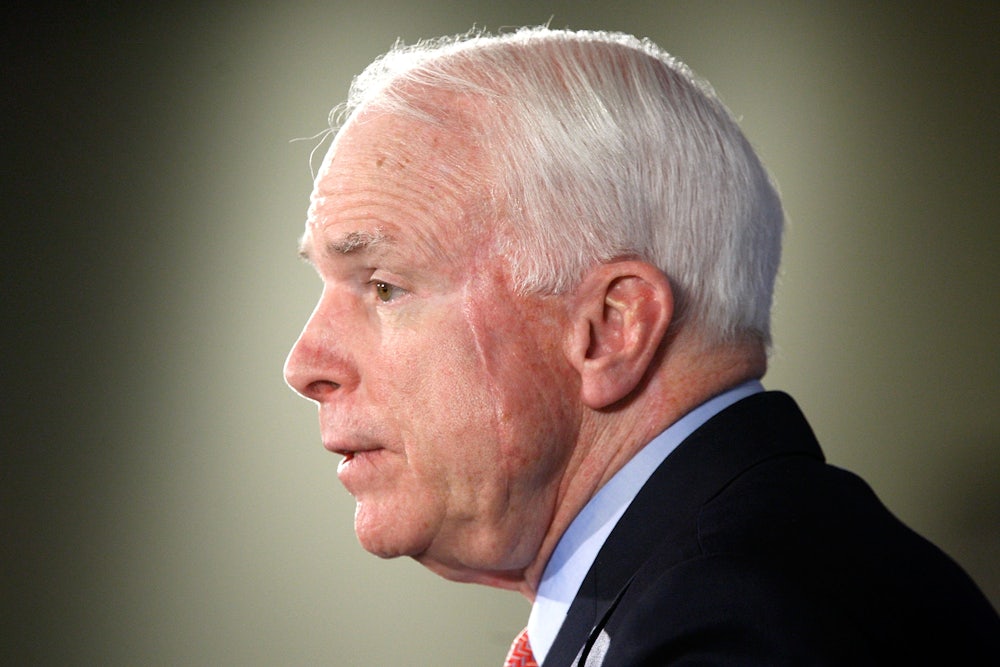

John McCain, who died Saturday at the age of 81, lived a long and eventful life, but the Arizona senator’s defining legacy may well be the feud he had in his last three years with Donald Trump. That quarrel has far-reaching implications for the future of the Republican Party and of America itself. In 2008, McCain was the standard bearer of the Republican Party in a losing presidential campaign. Eight years later, the GOP fell into Trump’s sway and McCain became an exile within his own party.

The battle between the two men was dramatic: McCain the war hero who preached sacrifice and national unity, Trump the draft-avoider who embodied greed and sowed division. Trump took every opportunity to mock and belittle McCain, infamously saying in 2015 the senator was “not a hero” and “I like people who weren’t captured.” At a recent event, Trump pointedly refused to spell out the name of a military appropriation bill that was titled in McCain’s honor. But McCain, as weakened as he was politically, also got in his licks. He was the most vocal of Trump’s critics in the party, and last year, with a thumbs-down for the ages, he cost the president a major legislative victory by voting against the repeal of Obamacare.

McCain was both the alternative to Trump and a precursor to the president. Before Trump took up the slogan “Make America Great Again”—or rather, lifted it from Ronald Reagan, whose 1980 campaign slogan was “Let’s Make America Great Again”—a group of conservative intellectuals, led by New York Times columnist David Brooks and Weekly Standard editor William Kristol, promoted the idea of “American Greatness” conservatism. Their preferred candidate was John McCain. The senator used that very phrase to bash Trump in 2016, calling the late Captain Humayun Khan, whose parents Trump had mocked, “an example of true American greatness.”

What’s the difference between McCain’s “American greatness” and Trump’s MAGA? These are clearly sibling doctrines, both variations of nationalism. American Greatness was, at least in aspiration, a forward-looking doctrine: a call for America to live up to its ideals. Domestically, it tried to be inclusive. McCain made a point of eschewing racism, as when he rebuked a supporter in 2008 for calling Barack Obama “an Arab,” and was an ardent proponent of immigration reform.

“American nationalism isn’t the same as in other countries,” McCain argued in his 2018 book The Restless Wave (co-written with Mark Salter). “It isn’t nativist or imperial or xenophobic, or it shouldn’t be. Those attachments belong with other tired dogmas ... consigned to the ash heap of history. We live in a land made from ideals, not blood and soil.” He also wrote, “The great majority of unauthorized immigrants came here to find work and raise their families, like most immigrants have throughout our history. They are not the rapists, killers, and drug dealers of fevered imaginations on the Right. They’re not the cause of the opioid epidemic.” (As so often, though, McCain’s noble words were belied his actions. In 2010, he ran for re-election under the slogan “complete the danged fence,” an anticipation of Trump’s “build the wall.”)

In foreign policy, American Greatness saw the United States as the confident, assertive leader of the West, willing and able to challenge foes. At its worst, it promoted military adventurism. In his better moments, McCain’s foreign policy had a larger sense of purpose than just military assertiveness, and included an awareness that America had a role to play in upholding the international order with diplomacy. In other words, McCain balanced nationalist belligerence with a sense of international responsibilities. This made McCain more mindful of cultivating alliances than other Republicans, and eager to protect America’s good reputation by foreswearing torture.

MAGA, by contrast, is a bitter, backward-looking nationalism. It has little use for immigrants, except as political foils (see Trump’s exploitation of the murder of Mollie Tibbetts), and is fueled by racial resentment. In foreign policy, MAGA sees the U.S. not as the pillar of the international order, but a sucker being exploited by allies. For Trump, good foreign policy is to get more out of other countries than they take, whether through plunder (“take the oil”) or shakedowns (starting trade wars, threatening NATO allies). And of course, Trump has openly extolled torture.

Yet if American Greatness and MAGA are two different paths of conservative nationalism can take, they do share a connection. By picking Sarah Palin to be his running mate in 2008, John McCain helped pave the way for MAGA and Trump. McCain wanted to energized the GOP base but he got more than he bargained for. Palin went rogue with atavistic resentment, most famously in her attacks on Obama for “palling around with terrorists.” It was a short distance between that and birtherism, which Palin also embraced. Trump was all but inevitable.

McCain was clearly uncomfortable with this turn. He saw little of Palin after 2008, and earlier this year expressed regret that he didn’t pick Joe Lieberman as his running mate instead. McCain also reportedly wants Obama to deliver a eulogy at his funeral—and has asked that Trump not attend.

In many ways, McCain was a conventional conservative, but he was more willing to work with Democrats than most post-Gingrich Republicans have been. This led to occasional heterodoxy, as in his support for campaign finance reform, his criticism of George W. Bush’s torture policy, and his vote against repealing Obamacare. But bucking the Republican Party line was something that McCain did only rarely, though he extracted maximum publicity when he did so. (He had a gift for endearing himself to the press.) In truth, he wasn’t quite the “maverick” that his most ardent fans held him to be. But his brand of American Greatness conservatism was far more flexible, and less polarizing, than MAGA.

Courage was surely the virtue McCain most admired. Born in 1936, he came from a long line of military men, stretching back back to the Revolutionary War. His father and grandfather were both admirals. He was a prisoner of war in North Vietnam from 1967 to 1973, suffering as much torture as any American who survived the war. His body had been shattered, shrinking from 160 pounds to 100 pounds. He could no longer bend his right knee or lift his right arm more than 45 degrees. Yet his mind remained intact, and he rebuilt his life when returning to America.

His political courage was shown in his willingness to fight with his own party, including Trump. When an aggressive form of brain cancer hit him last year, he again displayed his famous tenacity and willpower. His personal strength of character will be inseparable from his name for as long as he is remembered. But the inescapable truth is that when McCain died, American Greatness conservatism was already long in eclipse. He outlived his own ideology, which is unlikely to be resurrected anytime soon. In the contest between the senator and the president, McCain fought valiantly and admirably, but ultimately he lost to Trump.