Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign scrambled the electoral map, as he won several states that some considered reliably, even irrevocably, blue. This week’s midterms, blue wave or not, reversed some of those unexpected gains. While Republican candidates held the line in Ohio and apparently squeaked out narrow victories in Florida, voters turned leftward in three key states in the Upper Midwest. Some political observers now see a map that’s favorable to Democrats as they seek to topple Trump in two years.

“If Trump has lost the benefit of the doubt from voters in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan, he may not have so much of an Electoral College advantage in 2020,” election guru Nate Silver wrote on Thursday. New York magazine’s Gabriel Debenedetti pointed to resounding Democratic victories in some former purple states as a positive sign for Democrats: “It’s now hard to see how Virginia or Colorado, traditional swing states, begin 2020 anywhere but in the blue column, with Nevada leaning that way, too.”

What’s striking about both analyses, each written by sharp and well-informed observers, is the absence of discussion about the potential impact of voter suppression. While Americans will decide which presidential candidate to support based on the economy, immigration, and other issues, it’s increasingly clear that state election laws and rules will govern whether they can translate those decisions into actual votes. From Ohio to Georgia, Republicans have sought to constrain the electorate to their benefit. If they do so in several key states over the next two years, it may well decide the 2020 election.

Trump loves to talk about his Electoral College landslide, partly because it obscures his shellacking in the national popular vote and partly because it was a genuinely impressive victory. His path to the White House effectively ran through five states—Florida, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—though he did not need to win them all. Pennsylvania, Florida, and just one more would have sufficed. Clinton, meanwhile, could have lost Florida and still won, narrowly, by taking Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Instead, Trump won all five states and sailed into the White House with 306 electoral votes. Can he do it again in 2020? Trump has defied the odds before, but running the board in the Great Lakes region will be even harder the second time around. In 2016, Trump won by extraordinary close margins in three of the five key states: 10,704 votes in Michigan, 44,292 votes in Pennsylvania, and 22,748 votes in Wisconsin. Thanks to America’s peculiar system, a presidential election in which 138 million people cast their ballots came down to fewer than 78,000 voters in three states.

There’s evidence that voter-suppression laws may have helped tip the balance towards Trump. Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, who was ousted by voters on Tuesday, oversaw a series of changes that structurally tilted the state’s electoral contests toward Republicans. Shortly after taking power in 2011, Walker and state Republican leaders oversaw a gerrymandering process that ensured the GOP could win two-thirds of the state legislature’s seats even if they only won a majority of the total vote. He also signed a bill in 2015 that dismantled the state’s nonpartisan ethics and elections commission and replaced it with two commissions staffed by political appointees.

Walker’s most decisive legislation was a voter ID law passed in 2011, which required voters to present a government-issued photo identification when casting a ballot. Federal judges blocked the law from going into effect for years, citing the disproportionate impact it would have on black voters who often lacked the necessary IDs. When it went into force during the 2016 election, however, it appeared to have a critical impact, as Mother Jones’ Ari Berman reported:

After the election, registered voters in Milwaukee County and Madison’s Dane County were surveyed about why they didn’t cast a ballot. Eleven percent cited the voter ID law and said they didn’t have an acceptable ID; of those, more than half said the law was the “main reason” they didn’t vote.... [T]hat finding implies that between 12,000 and 23,000 registered voters in Madison and Milwaukee—and as many as 45,000 statewide—were deterred from voting by the ID law.

In two of the five key states, voting rights are relatively secure. Republicans in Pennsylvania passed a voter ID law in 2012, but state judges blocked its implementation two years later. (The state’s supreme court also won a showdown with state GOP lawmakers, striking down gerrymandered maps in favor of more balanced ones earlier this year.) Voters in Michigan, meanwhile, passed a measure on Tuesday that will enact automatic voter registration, same-day voter registration, and no-excuse absentee ballots. Democratic control of the state governorships in both states makes it unlikely that Republicans will pass new restrictions before 2020.

The same can’t be said for the two major perennial swing states on the list. Ohio Republicans won big on Tuesday at all levels, save for a U.S. Senate seat successfully defended by incumbent Democrat Sherrod Brown. The defeats of gubernatorial contender Richard Cordray and secretary of state candidate Kathleen Clyde leave Democrats with scant influence over the state’s election laws headed into 2020. Clyde’s loss in particular is stinging: As a state lawmaker, she championed reforms like automatic voter registration and opposed Republican efforts to impose new restrictions.

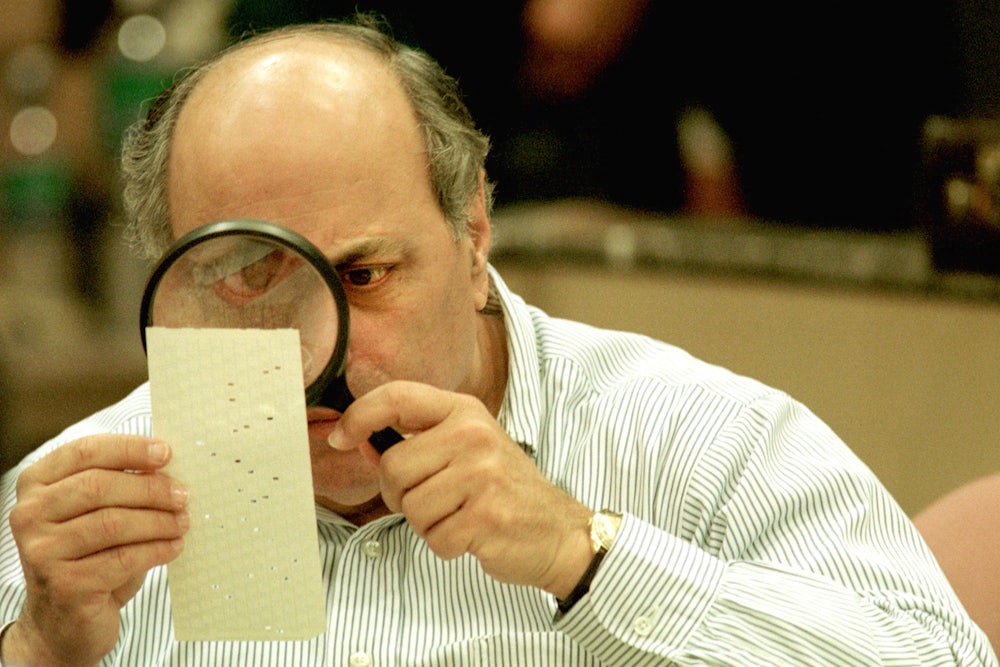

Ohio has a reputation for stringent measures aimed at its own electorate. Earlier this year, the Supreme Court narrowly upheld Ohio Secretary of State Jon Husted’s controversial purge of the state’s voter rolls. The state purged more than two million voters from its rolls between 2011 and 2016, removing voters who had died or moved as well as thousands who had simply not cast a ballot in recent elections and failed to return a notice. Ohio lawmakers also passed strict voter ID laws, which the courts blocked, and sharply cut early voting access, which the courts didn’t.

In Florida, where Republicans have controlled the levers of power for a quarter-century, restrictive voting laws are a persistent threat. In 2012, under Governor Rick Scott, state officials brawled with the federal government over a campaign to remove suspected noncitizens from the state’s voter rolls by using flawed data that disproportionately targeted nonwhite voters. He imposed new barriers on Floridians who sought to regain their voting rights after completing their sentences—changes that favored white and Republican applicants over those from other backgrounds. In 2011, he signed a controversial law that cut early voting days in half and made it harder for third-party groups to register new voters. Will Republican governor-elect Ron DeSantis, assuming he survives a potential recount, pick up where Scott left off?

Republicans often justify strict voter laws by pointing to the illusory threat of voter fraud. In many cases, however, we know that the real motives are more sinister. Former Florida GOP officials, including former Governor Charlie Crist and former party chairman Jim Greer, admitted to the Palm Beach Post in 2012 that state lawmakers used voter fraud as an excuse to pass laws that would make it harder for Democratic voters to cast a ballot. Republican officials elsewhere have given up the game from time to time: The leader of Pennsylvania’s state House predicted in 2012 that the state’s voter ID law would help Mitt Romney win there over Barack Obama, while Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel openly credited their version with electing Trump in 2016.

In a healthy democracy, there would be no need to worry about whether the 2020 election will reflect the will of the American people. Thanks to the Supreme Court’s recent aversion to protecting voting rights, and a decade of manipulation by state GOP officials, that basic principle can’t be guaranteed. One party is trying to win elections, and the other is trying to make winning impossible for anyone else.