After two months of refusing to face the true proportions of the coronavirus pandemic head-on, President Donald Trump sought to reassure panicked citizens—and financial markets—in an address to the nation in early March. The president stressed, without any solid evidence, that America had been remarkably successful in containing the spread of the virus, and was making additional headway in streamlining effective and affordable treatment for infected Americans. The main new measure he touted, however, highlighted just how disastrous his administration’s response to the crisis had been since the virus first arrived in the United States back in January: Re-upping America’s prior policy of aggressive border closure, Trump announced that the United States would be suspending entry of travelers from Europe, where the coronavirus was then spreading with alarming speed.

Trump’s March 11 speech to the nation from the Oval Office showed in no uncertain terms that his administration and his senior advisers on the crisis had failed to adapt in any serious way to a mounting public health emergency. By recurring once more to the issue of border security—a key demagogic theme of his 2016 presidential campaign—Trump ignored what was by then an obvious truth of the coronavirus pandemic: National borders mean nothing to a virus seeking host organisms.

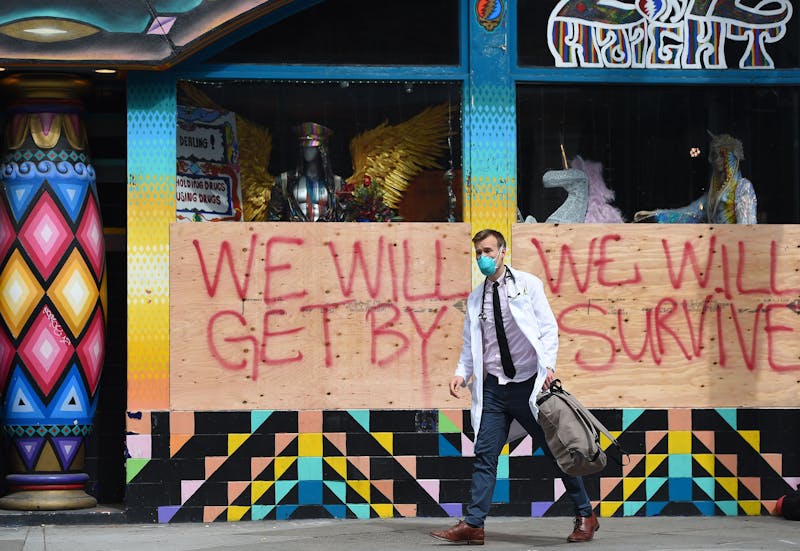

The markets Trump sought to soothe above all else responded unambiguously the following day, with one of the most dramatic single-day falls in the history of the New York Stock Exchange. Despite a frantic collateral infusion of $2 trillion from the Federal Reserve, New York markets went on to suffer the worst day in history on March 16, falling nearly 13 percent. Throughout March, the world’s financial markets dropped precipitously, recovering only after central banks engineered still greater additions of cash—and then they fell again. As major cities across America took their own measures to slow viral spread, placing millions of citizens under work-from-home orders and closing nonessential businesses, unemployment skyrocketed and small businesses collapsed. Stocks, again, descended until the end of March, when Congress passed a $2.2 trillion stimulus package.

As one leading economist put it, speaking on background, “We’re in uncharted territory. Anybody who says that they know what’s going on is wrong. Overall, we are looking at the largest shock and the largest drop in employment and output since [World War II]. Even if the virus situation resolves itself soon, dislocations in financial markets will linger.”

In the face of all these convulsions, Trump and his backers remained very much on message, and keen to place blame for the crisis elsewhere. The president’s strongest supporters labeled the Covid-19 threat a hoax, conjured by the liberal media to make Trump look bad—a claim the leader himself endorsed at a rally in South Carolina. Appearing on Fox & Friends on March 13, the Rev. Jerry Falwell Jr. said people were “overreacting” and denounced virus worries as the liberal establishment’s “next attempt to get Trump.” Falwell went on to suggest that the virus itself was manufactured in North Korea in collusion with China. Queried about specifics, Falwell simply shrugged and replied, “I don’t know, but it really is something strange going on.” Later that month, Falwell reopened Liberty University to more than 1,000 students, at a time when universities nationwide had sent their young people home, reverting to homeschooling via internet to minimize potential spread of the virus.

There’s no small irony in the now-widespread initiative on the right to blame China and other sinister Asian powers for the virus’s devastating spread across the globe: The Trump administration’s response to the virus was replicating, in all its major outlines, the way that the Communist Party leadership in China had badly bungled its own initial reaction to the coronavirus outbreak in and around the major city of Wuhan. Both Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping instinctively sought to repress news of the true danger of their countries’ outbreaks, and the reach of their infection zones, so as to minimize potential political damage to their regimes. Both leaders, displaying parallel if historically distinct brands of authoritarian rule in a crisis, sought to dismiss the counsel of suspect health professionals and other experts. In both China and the United States, this politicized deafness to elementary scientific precautions would diminish the critical early-phase adoptions of broad-based social cooperation and early quarantines to flatten the curve of newly diagnosed coronavirus cases, thereby containing the disease’s spread and potential lethality. And both leaders doubled down on their dire initial misreadings of their respective crises as evidence continued to mount that their citizens desperately needed the broader dissemination of information and public health resources in order to weather the outbreak. The larger political story of the 2020 coronavirus crisis, in other words, may well prove to be a powerful case study in the way that governments controlled by leaders prone to unilateral decision-making, and the top-down information regimes they rely on to perpetuate their rule, are all but guaranteed to create maximum conditions of public health breakdown.

This disarming parallel becomes clearer still when we revisit the history of the virus’s transmission, and its eventual westward trek toward the United States. Again defying the brute nationalist logic of border closure, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has spread as an unseen stealth agent among us, causing illness and death. By the time it first arrived on U.S. soil, carried by an unknown traveler from central China in the middle of January, the Chinese propaganda campaign denying any pending pandemic was in full swing. Chinese scientists had by then announced successful identification of the mysterious, novel virus, and government officials insisted that it had originated in the live Hua’nan animal market in central Wuhan. The government-approved data then sought to minimize the outbreak—much as Trump would later tout, in a surreal news conference, the politicized tactic of keeping passengers quarantined on a cruise line to make his own coronavirus numbers look good. Chinese officialdom then reported that just 41 people were diagnosed with the new pneumonia disease, with only one fatality. Accordingly, no particular control measures had been undertaken to contain what was then being made to appear a manageable scale of “flulike” infection.

Things had gone on like this for nearly three weeks. Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and government officials in Wuhan, population 11 million, and surrounding Hubei province, inhabited by another 48 million people, insisted everything was under control. On January 13, the Wuhan Commission on Health proudly announced that “there were no new cases of pneumonia caused by new coronavirus infection in our city, one case was cured and discharged, and no new deaths were reported.”

As late as January 14, Chinese government representatives officially reported to the World Health Organization that there was “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus identified in Wuhan,” a point they would stress again on January 20. And on January 18, with the blessing of Wuhan authorities, 40,000 people gathered for a traditional Lunar New Year celebration in which households prepared special dishes and shared them widely, with participants dipping their chopsticks into one dish after another.

Three days earlier, a man in his thirties flew from Wuhan to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, and went to his home in Snohomish County, Washington. On January 19, he was diagnosed with a probable case of the Wuhan pneumonia. It was also true that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—where Trump had previously discharged much of the pandemic preparedness team largely on the grounds that the Obama administration had taken pains to build up its ranks—had no test to definitively prove that he was infected. But the man clearly fit the official American diagnosis of the moment: high fever, pneumonia, and recent travel from Wuhan, China. When asked about the ailing Seattle-area man in a press briefing at the World Economic Forum, President Trump insisted, “We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China. We have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”

Fortunately, the information brownout in China was at this point beginning to show signs of cracking. As the population in Wuhan fell seriously ill in greater numbers, a double-digit official count of Covid-19 victims was simply no longer credible. So Chinese President Xi Jinping threatened to fire Wuhan authorities for concealing news of the virus’s spread, and by January 22, new numbers were released, revealing a surge of 444 cases of the strange pneumonia, with 17 official deaths. Again, these numbers didn’t tally new infections, but freshly released old data. With China’s Lunar New Year holiday approaching, Beijing ordered a travel ban, beginning the lockdown of Wuhan—but not before some five million people fled the metropolis, taking the virus with them. The critical pre-holiday moment of mass incubation for the virus again underlines how crucial it is to maintain transparent flows of information in the face of a public health crisis. Even though China was gradually shifting its footing, in at least acknowledging a nationwide epidemic was in the making, the larger information lag was still pronounced, particularly as the spread of Covid-19 went global. As the world health community was starting to learn of a SARS-like new pneumonia virus spreading in China, government officials in that country were still downplaying its true severity.

By January 26, China had placed more than 50 million people under quarantines of one kind or another, as 30 provinces reported a total of 2,744 cases with 80 deaths (the eventual number of Chinese citizens placed under quarantine or restricted movement protocols would soon reach nearly 100 million). That same day, five coronavirus cases were known in the United States, spread out over four states.

With the threat of a pandemic now looming, Washington officials began formulating a response to the spread of the coronavirus in line with their overarching policy assumptions—namely, a strategy to protect Americans by screening travelers and flights to U.S. airports.

The keep-the-virus-out strategy started on Friday, January 17, as a screening procedure at three U.S. airports—San Francisco, Los Angeles, and JFK in New York. Passengers arriving from Wuhan were screened by Department of Homeland Security and some 100 CDC personnel for fevers, coughing, and breathing difficulties. If observations turned up potential symptoms of the new disease, passengers were isolated and further evaluated, based on their clinical features and their responses to a questionnaire regarding activities they had engaged in while in Wuhan. Again, following the example of Chinese leaders, U.S. federal officials instructed airports to screen aggressively for any travelers returning from China who had visited the live animal market in Wuhan, which, according to government reports there, was the source of all the known Chinese cases.

President Trump wasn’t then particularly focused on the specter of a new breed of pneumonia at our border: He had other crises on his mind. Within his administration, a feud was unfolding, chiefly between Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar and Seema Verma, the head of Medicare and Medicaid, over appropriate uses of health care funds and allegations of misappropriation by Verma. That dispute was adding fuel to more widespread tensions within the administration about how to scale back or eliminate the core provisions of the Affordable Care Act—an effort Trump had repeatedly tried to push through Congress with disappointing results. Far more distracting for the president, however, was his Senate impeachment trial, which started on January 16, following lengthy hearings and voting in the House.

With the White House caught up in the drama of the president’s Senate acquittal, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and his staff took the lead on responses to China’s outbreak. In keeping with Pompeo’s office’s priorities and wider administration preferences, the emphasis was once more on travel and border control. Pompeo warned Americans not to visit Wuhan, and to avoid travel to China over the Lunar New Year celebrations scheduled to start on January 25—a signature event for Chinese that typically features the largest internal mass migration in the world, with hundreds of millions of people returning to their ancestral villages for days.

On January 21, however, the CDC announced that restrictions had failed to prevent at least one case from slipping through the airport-based safety net—the Snohomish County traveler’s infection was publicly acknowledged. But far from highlighting the limitations of a borders-first approach to containing the virus’s spread, the first confirmed case of international transmission within the United States prompted the Trump administration to redouble its commitment to this misguided policy. For weeks, the crux of the Trump White House’s coronavirus response was akin to pulling up the drawbridge over the castle moat, hoping the virus couldn’t swim and scale the fortress walls. Public health experts—both outside and within the administration—warned that America had better prepare for a breach of the castle walls, but such pleas mostly fell on deaf ears in Washington. In lieu of a more effective program based on early testing and social separation, Trump officials grudgingly endorsed a modest-at-best set of measures to heighten domestic preparedness for a potentially lethal pandemic.

This was, of course, Donald Trump’s comfort zone. During the global Ebola outbreak of 2014–2015, Trump had tweet-shouted a series of demands for the same basic travel restrictions to keep Ebola-infected health care workers out of the United States. Now facing a public health crisis of far greater proportions, Trump continued to insist that closing borders was the key to American infection control, and he would continue to do so for weeks. At one point, he even suggested that Covid-19 justified closing the U.S. border with Mexico; even though the southern border didn’t represent a principal avenue of transmission for the virus, it was a tried-and-true source of nationalist panic that Trump could gin up among his base. Two months later, on March 9, Trump would look back on this moment of lifting America’s drawbridge to announce on Twitter, “The BEST decision made was the toughest of them all - which saved many lives. Our VERY early decision to stop travel to and from certain parts of the world!”

In an administration notoriously organized around displays of sycophantic loyalty to the president, Trump officials duly went forth to echo the message. As late as early March, with the virus spreading nationwide and financial markets tanking in response, senior economic adviser Larry Kudlow was still insisting that the Trump border strategy had all but contained the virus’s spread in the United States. “This came unexpectedly, it came out of China, we closed it down, we stopped it, it was a very early shut down,” he told CNBC. “I would still argue to you that this thing is contained.”

This was plainly a lie. The airport safety net hadn’t worked in 2014, when Thomas Eric Duncan traveled from Monrovia, Liberia, to Dallas, Texas, to visit relatives, and received his Ebola diagnosis a few days later. His case was initially misdiagnosed as the flu, and while he was treated, the Ebola virus spread to health care workers in the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. Worse, by January 26, Chinese authorities announced that the virus was spreading via person-to-person contact—with the spreaders often by all appearances completely well, without any observable symptoms. This development should have been a red flag about the reliability of airport screening procedures worldwide.

More to the point, the Trump border-first approach failed because the SARS-CoV-2 virus was already in America before the State Department issued its travel guidance and airport screening commenced. And it failed because China stifled news about what was really transpiring in Wuhan and across the nation.

This is why the 2020 pandemic is, at its root, the story of two deeply flawed leaders, Xi Jinping and Donald Trump, who for too long minimized the coronavirus threat—and who, because of the enormous, largely unaccountable power they wield, must share responsibility for its global scale. At key moments when their mutual transparency and collaboration might have spared the world a catastrophic pandemic, the world’s two most powerful men fought a war of words over trade policies, and charged each other with responsibility for the spread of the disease. When scientists worldwide could have benefited from details of China’s new disease, perhaps thereby preventing thousands of hospitalizations and deaths, the Chinese Communist Party’s instincts were to arrest conveyors of information, shut down social media, and prohibit visiting teams of World Health Organization and foreign disease-control experts.

For its part, the United States was uniquely positioned, thanks to the chronology of the outbreak, to learn from China’s initial mistakes, and heed the example of the Xi regime’s belated epidemic control efforts. The order of the day, as all sorts of public health experts and officials from past administrations had stressed at the time, was to kick on-the-ground prevention and containment efforts into high gear. To begin with, Trump officials should have been preparing lab tests, hospital infection control plans, supply chains of vital equipment, and implementing a chain-of-command reordering of governance on an emergency footing. They should also have been securing budget proposals for emergency funds, and overseeing fuller coordination with state and local health departments across American states and territories.

Instead, the main message of the Trump White House was stunningly oblivious to the real emergency the country was facing. Addressing a press conference at the World Economic Forum on January 22, President Trump insisted that when it came to the coronavirus threat, “We have it totally under control,” despite the Washington state case. “It’s one person coming in from China. We have it under control. It’s going to be just fine,” he said. For good measure, he added that he had a “great relationship” with Xi, who assured him China’s epidemic was also controlled.

“Control” was the shared mantra for both leaders. “The Coronavirus virus is very much under control in the USA,” Trump tweeted on February 24, adding, “CDC & World Health have been working hard and very smart. Stock Market starting to look very good to me!” Similarly, on March 5 Trump insisted via Twitter, “With approximately 100,000 CoronaVirus cases worldwide, and 3,280 deaths, the United States, because of quick action on closing our borders, has, as of now, only 129 cases (40 Americans brought in) and 11 deaths. We are working very hard to keep these numbers as low as possible!”

It wasn’t hard to hear the same sentiments echoing through the centers of power in China. “I have at every moment monitored the spread of the epidemic and progress in efforts to curtail it, constantly issuing oral orders and also instructions,” Xi asserted.

It’s unlikely the world will ever know who patient zero was in the Wuhan outbreak, or from what animal that first human being acquired the deadly virus. But genetic analysis of strains of the coronaviruses found in bats, other animals, and people offers two general insights. First, the virus that was already circulating among the human population in Wuhan in early December is 96 percent identical to a virus found in fruit bats. It’s undoubtedly an ancient virus that has inhabited some types of bats, without apparent harm to the animals, for tens of thousands of years. Somehow—possibly inside Wuhan’s Hua’nan live animal market—a bat’s urine or saliva passed to some other caged beast, infecting that animal. Genetic evidence hints—but does not prove—that the intermediary animal was a pangolin, an unusual type of burrowing mammalian anteater that is covered in scales and curls itself into a tight ball when under attack. The most trafficked mammal in the world, pangolins are at risk of extinction because their scales are coveted by practitioners of Chinese traditional medicine, who believe that in powdered form they cure arthritis and other ailments.

Regardless of the original genesis of the virus’s spread among humans, it’s now clear that unseen cases of the mysterious pneumonia were present in Wuhan at least as early as December 8, 2019, and may well date back to November, even October. According to the South China Morning Post, leaked government documents show testing of old pneumonia patient samples in Wuhan revealed infections dating back to November 17, 2019. This fateful event—the transmission of a bat virus, to an intermediary species, to a person—occurred rapidly and recently. The full analysis of viral genes shows it was a natural occurrence, meaning that (in spite of xenophobic conspiracy theories propagated by right-wing media sources and disseminated by at least one Republican lawmaker) the human virus was not concocted in a laboratory. One Chinese study suggests that the bats carrying the virus came from Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, an island archipelago that is a popular Chinese tourist destination.

All epidemics start with a single case. And the key to stopping an outbreak is recognizing that something new, and dangerous, is unfolding before that one case becomes 20, or 50, or 100. In Wuhan, the crucial inflection point for the virus’s broader transmission occurred over a six-week period, from early December to January 15. During that time, the numbers of infected people and their concentration within a fairly compact area inside Wuhan might have rendered the outbreak quickly manageable. But a sorry trail of mistakes, cover-ups, and lies from Chinese authorities led health officials and Communist Party leaders to block appropriate investigations and conceal information that would certainly have provoked an earlier, more aggressive response.

Careful analysis of the first 41 patients admitted to Wuhan’s top infectious diseases hospital, Jinyintan, disclosed that just 27 of the cases had any direct or secondary link to the blocks-long Hua’nan animal market. The earliest reported case involved a subject who experienced symptoms on December 1, though he wasn’t diagnosed with pneumonia until more than a week later. Neither he nor the other 13 patients in this first group who had not recently visited the market seemed to be linked to other known cases. This suggests that there was already widespread community transmission inside Wuhan well before the Christmas season. Another study of these and 384 other patients who took ill in Wuhan during the month-plus official cover-up in China showed that the only individuals linked to the Hua’nan market were among those diagnosed before January 1. (Nothing is known about the earliest case later discovered in Wuhan—the individual who was hospitalized on November 17—but it’s now clear that 266 Chinese were suffering from the coronavirus before the Western New Year’s Eve.)

At this point in the chronology of the outbreak, spread was entirely human-to-human. Crucially, the first known case of individual exposure involved someone who had not set foot in the Hua’nan market. In other words, that decisive moment when someone first caught the coronavirus infection might not have even occurred in Wuhan. None of the early cases involved patients under the age of 15; the median age was 59. And the virus was spreading fast—each infected person was passing contagion to, statistically speaking, 2.2 other people, meaning the epidemic was “doubling in size approximately every 7.4 days in Wuhan at this stage,” according to the study.

It’s possible, perhaps probable, that the Hua’nan was only coincidentally connected to the world’s pandemic. Chinese state media reported that 31 swabs of surfaces inside the market (out of 585 taken) tested positive for the virus on January 1, but that data was never published in any duly tested or reviewed scientific literature. (At that time, scientists who had visited Wuhan told the South China Morning Post that there was evidence of human-to-human transmission.) Nevertheless, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, after initially suppressing all information regarding the outbreak, changed narratives on December 31, acknowledging there was a virus on the loose, 27 people were infected, and it emphatically was not the SARS virus. The report also insisted that the outbreak was connected to the Hua’nan market, which local government authorities had shut down. Everything was under control, Chinese citizens were assured by their authoritarian regime.

But doctors inside Wuhan were already sharing contrary news. Wuhan Central Hospital had a patient in December whose lungs were filled with fluids—a sign of immune system reaction to acute infection. Doctors there spread the word among colleagues that the patient did not respond to antibiotics—meaning in all likelihood that the infection was viral, not bacterial. One by one, other hospitals began sharing similar findings, and whispering that it looked like SARS. On December 30, according to a Wall Street Journal investigation, Wuhan Central physician Ai Fen passed on to colleagues the results of a lab test she ordered on one such patient, which came back reading “SARS coronavirus.” Ai would eventually be reprimanded by her bosses for publicizing her findings. A short while later, another Wuhan Central doctor, ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, went into a physician group chat room to inform his colleagues across Wuhan, “7 SARS cases confirmed at the Hua’nan Seafood Market,” noting that the patients were quarantined. He added, “Don’t leak it. Tell your family and relatives to take care.”

The following day, Li and seven other physicians were summoned before Wuhan police, and compelled to sign confessions of “spreading rumors” and disseminating false information. Their chief crime, the octet were told, was in claiming the disease looked like SARS. Ai, summoned to the Disciplinary Office of Wuhan Central Hospital, was chastised for “manufacturing rumors.” Ai would later post an online account of her work, detailing her experiences with authorities and the virus, and her army of admirers across China would use clever cyber-tactics to stay seconds ahead of government social media censors, sending the writings all over the Chinese-speaking world.

The World Health Organization accepted China’s official explanation of the disease’s limited, and theoretically containable, human genesis in the Hua’nan market in a statement released from Geneva on January 1: “The evidence is highly suggestive that the outbreak is associated with exposures in one seafood market in Wuhan. At this stage, there is no infection among health care workers, and no clear evidence of human to human transmission.”

Days later, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission announced there were 44 cases of the mysterious new disease in Wuhan. On January 5, the panel emphatically restated that the cause was not SARS, telling the World Health Organization that there were now 59 cases—all of which remained, somehow, linked to the Hua’nan market. Most of this spike in reported cases reflected reappraisal of old pneumonias that hadn’t previously been ascribed to the new coronavirus, dating back to December 12. Once again, Wuhan authorities insisted there was no expanding epidemic—just a retrospective accounting.

But there must have been some greater cause for alarm, because on January 7 President Xi Jinping personally took control of the epidemic response, and maintained control throughout, according to a speech he delivered to senior Communist Party officials. For days, presumably under Xi’s orders, Wuhan reported stagnant epidemic figures, even on one day lowering its count. The figures were lies.

Closing down Hua’nan had no impact on the spread of viral pneumonia in the city, and nearly everybody working on the front lines in Wuhan’s hospitals was convinced that the virus was passed human-to-human—a terrifying new development that the higher reaches of Chinese government were working hard to suppress. It is now known why: 86 percent of all viral transmission was undetected in Wuhan prior to January 23, and 79 percent of all transmission was coming from undocumented sources—people who either were asymptomatic, or simply had been noted by the widening safety net of disease surveillance.

In Beijing, the National Health Commission assembled a distinguished team to investigate Wuhan, including George Gao, the head of China’s CDC; retired infectious disease physician Zhong Nanshan, often described as the man who discovered SARS; and virologist Yuen Kwok-yung from Hong Kong University, one of the world’s most respected experts on the coronaviruses and influenzas. The team was appalled by what they saw in Wuhan, according to Yuen, who was already convinced a catastrophe was unfolding. On January 4, he urged Hong Kong to close its borders to the mainland: Though borders remained open for a few more days, Hong Kong did declare a state of emergency—much to Beijing’s chagrin, given months of demonstrations in the independence-minded territory.

It was obvious to the expert team that Wuhan health authorities were “putting on a show,” Yuen said—trying to prove that they had the virus contained just as it was starting to break out into new infected populations. But Wuhan had no testing kits to tell who was, or was not, infected—the first batch would arrive from Beijing on January 16. Well before then, Yuen and his colleagues at Hong Kong University invented their own test for the virus, and started administering it across southern China and Hong Kong. With it, they discovered on January 10 a Shenzhen family infected with the coronavirus—clear evidence of person-to-person transmission. But the National Health Commission in Beijing censored publication of that discovery—thereby blocking any chance to warn physicians that the virus could potentially be spread from a patient to a health worker or family member.

During their team visit, CDC Director Gao said the Hua’nan animal market was filthy and disgusting, and both he and Yuen were shocked to see that it was just a few yards away from the most important high-speed train hub in all of China, Hankou Railway Station. This station connects not only all major cities of the nation, but the entire Belt and Road Initiative—Xi Jinping’s brainchild massive economic mission to re-create the Silk Road ancient ties between Beijing and most of Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Eastern Africa. At the heart of Xi’s Belt and Road dreams sat Wuhan, whose Wuhan Tianhe International Airport was used by 27 million people a year, flying all around the world. The station accounted for well over 100 million passenger trips a year.

The team returned to Beijing, telling Xi’s office that the epidemic was out of control. There was clear evidence of person-to-person transmission, the researchers announced, and also noted that the Hua’nan market had little, if anything, to do with the crisis. Zhong went further, telling Chinese reporters that 14 health care workers had contracted the virus, and it clearly posed an epidemic threat to all of China.

By the third week of January, with the Lunar New Year holiday looming, it was time for a new official narrative: Beijing had to step in, blame local incompetence, fire Wuhan politicians, and bring in the big guns. As the crisis mounted, critics began taking the risky step of calling out China’s dishonest handling of the crisis on Chinese social media, with posts popping up faster than censors could tear them down. A new call for transparency came down from a CCP Twitter account on January 21: “Anyone who puts the face of politicians before the interests of the people will be the sinner of a millennium to the party and the people,” it read, and added that “anyone who deliberately delays and hides the reporting of [virus] cases out of his or her own self-interest will be nailed on the pillar of shame for eternity.”

Suddenly the numbers of reported cases skyrocketed, and Beijing formulated plans to lock down the entire city of Wuhan, cut travel for the Lunar holiday all over the nation, and revert to clampdown mode. Chinese officials began employing security tools, such as monitoring social media postings, deploying artificial intelligence video scanning of groups gathered in discussions, and police interrogations to control public behavior and manage public fear. Because SARS in 2003 had only been contagious from ailing individuals who were running fevers, the entire containment strategy for that disease was based on thermometer guns. At all points of transit, along barricaded highways, at building entries, and in stores, citizens were compelled to undergo fever checks, often several times a day. If they were found to be running temperatures, they were hustled off to quarantine centers and hospitals, where they remained for a minimum of two weeks.

Over the next two weeks, Wuhan came under increasingly tight control, with nearly the entire population confined to their apartments. Massive hospitals were built in a matter of days to house critically ill patients. Police arrested individuals who refused to wear masks and rounded up suspected Covid-19 cases off public streets. The tools of the security state were put to full use, censoring social media, arresting Chinese journalists, and issuing a new round of trust-the-leadership-caste propaganda.

After twice declining to do so, the World Health Organization declared China’s outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30. By then, the virus had spread to 18 countries. China escalated its lockdown, mobilized military medical cadres to assist exhausted—and, in some cases, dying—doctors in Wuhan. The death toll soared, bodies were left stacked on hospital floors and in the streets. By February 3, more than 17,000 cases were officially tallied.

On February 7, the whistleblower physician Li Wenliang, who had become a social media hero across China, died of the disease at the age of 34. His death sparked a massive outpouring of rage and grief across China that spurred even timid, ordinary people to shout from quarantine and post on social media their anger at the Communist Party and Xi Jinping. It was a Chernobyl-like moment for the Chinese leaders, as a regime of autocratic social control cultivated over the course of decades suddenly appeared to snap.

By March, China’s leaders were breathing somewhat easy again. As I write this in mid-March, reported new cases in China have dramatically tapered off. And inside Wuhan the numbers fell to such low levels that all the quarantine centers and newly built disease hospitals were closed. Nurses danced in their protective suits, flashing victory finger signs. Slowly the people of China began to feel safe, returning to work.

The saga of the virus’s tour through China should have put the United States on notice against the sorts of face-saving official measures that work in the larger scheme of things to compound the conditions of viral transmission rather than to contain them. And at times there were faint causes to hope that this might in fact prove to be the case. In early February, President Donald Trump tweeted a vote of confidence in Xi Jinping, writing, “Just had a long and very good conversation by phone with President Xi of China. He is strong, sharp and powerfully focused on leading the counterattack on the Coronavirus. He feels they are doing very well, even building hospitals in a matter of only days. Nothing is easy, but he will be very successful, especially as the weather starts to warm & the virus hopefully becomes weaker, and then gone. Great discipline is taking place in China, as President Xi strongly leads what will be a successful operation. We are working closely with China to help!”

But that February 7 message bore almost no substantive relation to the Trump administration’s own coronavirus response. Trump and his senior advisers remained confident that border closures and airplane shutdowns would keep Covid-19 out of America—and so the White House took almost no interest in the potential of a pandemic sweeping America. In 2018, Trump had eliminated most of the Obama-era pandemic response capacities inside federal agencies, especially the National Security Council and Department of Homeland Security—which meant that Trump was dangerously insulated from critical sources of information about America’s acute vulnerability to emerging viral threats. The Trump administration had no coordination of information and analysis in the National Security Council, no command operation inside the Department of Homeland Security, a diminished set of global health and epidemic programs at the CDC, lapsed funding for training grassroots medical personnel in infection control, and a weakened capacity to rush diagnostics, drugs, and vaccines through FDA safety checks and approval.

Despite warnings from his own national intelligence community that Covid-19 displayed “pandemic potential,” the president insisted the Chinese outbreak posed no threat to America. Some critics have labeled this call “the worst intelligence failure in U.S. history,” comparing it to past American leaders’ neglect of crucial reports of hostile activity prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the 9/11 attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center.

This disconnect came into full view just days after Trump had hailed Xi’s belated initiative to contain the spread of the coronavirus in China. In one press conference after another, Trump struggled to give any coherent accounting of American plans. Meanwhile, the Dow Jones sank day by day, the numbers of ailing Americans rose, and the United States earned the distinction of being likely the only wealthy country in the world that was unable to mass produce diagnostic tests to determine just who was infected and how best to treat them and isolate them.

As viral testing finally rolled out on a minute scale in the first week of March, the American public learned of pockets of community transmission of the disease all over the country—especially near Seattle and New York City. Stock markets continued their steep slide. Some institutions, such as schools and nursing homes, shut down; the National Guard was dispatched to help enforce quarantine conditions in the viral hot spot of New Rochelle, N.Y.

It was clear that little was being done at the federal level to quell the spread of the virus—and citizens increasingly felt desperately thrown back on their own limited resources to contend with the specter of a long-term, lethal pandemic. By the time of Trump’s March 12 special address to the nation, much of the American public already knew the awful truth: that the entire Trump administration strategy for protecting them from Covid-19, which rested on airport controls to keep the virus out of the country, was a nonstarter. The virus was already all over America.

Desperate to keep “the numbers where they are,” as the president put it in a press briefing at the CDC, the White House seemed determined to draw from the Xi Jinping playbook—censoring data, and clamping down on concern and dissent within the administration.

And just as politics has largely dictated the woefully inadequate American response to the coronavirus threat, so will politics shape our reactions to this colossal governing failure. Our political system, together with the media ecosystem that relies on it, has grown notoriously polarized. The nation is facing a heated presidential election, and the coronavirus threat has supplied charged ideological fodder in political salvos from all sides. Until the first reports emerged of community-acquired Covid-19 cases within U.S. borders, America seemed satisfied to act as a collective epidemic voyeur, watching horror unfold in China and elsewhere overseas without anticipating its arrival domestically. As outbreaks exploded in South Korea, Iran, Japan, and Italy, anxiety rose in financial markets, fretting about quarantine conditions and supply-chain disruptions poised to extend well beyond the already collapsed production and distribution networks in China.

As longtime China-watcher Bill Bishop wrote for his website Sinocism, “We might be heading into [the] first global recession caused by [Chinese Communist Party] mismanagement. Previous manmade disasters in China since 1949 never really spread outside the PRC’s borders in meaningful ways. This time looks to be different, and being the proximate cause of a global recession may not be helpful to the PRC’s global image and aspirations.”

Chinese leaders clearly heeded this threat. China rolled out a propaganda campaign, accusing the United States of responsibility for the pandemic, and complaining that other world powers weren’t following its example.

Inside China, meanwhile, Xi waged a propaganda effort to shore up his damaged image as a great leader, visiting factories and hospitals. After one such visit, the state-run media issued this glowing report: “The inspection tour by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Wuhan, Central China’s Hubei province, has greatly inspired Chinese society. People interpret the visit in their own simple way, and optimism has blended with the atmosphere of spring.”

Eager to get his economy back on track, Xi ordered key factories and industrial centers reopened—only to have some efforts backfire. On March 11, as the South China Morning News described it, “At 8.30am the government of Qianjiang—which lies about 150 km (90 miles) east of Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province—said that all restrictions on the movement of people and traffic would be lifted at 10am. They were.

“Then, at 10.30am, they were reinstated.

“‘The city will continue its restrictions on the movement of traffic and residents,’ the government said, without elaborating.”

Two days previously, well-known Chinese author Fang Fang wrote a tough essay, labeling the epidemic (not the virus) “man-made” and insisting, “Now is the best time for reflecting on what happened and investigating who is responsible.” Pointedly, she rejected CCP claims that the people should thank the party for stopping Covid-19. “A word that crops up frequently in conversation these days is ‘gratitude.’ High-level officials in Wuhan demand that the people show they’re grateful to the Communist Party and the country. I find this way of thinking very strange. Our government is supposed to be a people’s government; it exists solely to serve the people. Government officials work for us, not the other way around. I don’t understand why our leaders seem to draw exactly the opposite conclusion.”

Outside the country, China waged a two-pronged effort: one showing its willingness to help the rest of the world, the other leveling accusations and blame. At the forefront of this PR offensive is the country’s United Nations Ambassador Zhang Jun. In a March 10 letter to all 192 member-states of the United Nations, Zhang wrote, “The spread of the epidemic has been basically contained in Hubei and Wuhan. We are ready to strengthen solidarity with the rest of the international community to jointly fight the epidemic.”

CCP leadership noted that the “comprehensive, thorough and rigorous” measures China took to bring its epidemic to a halt could be shared with the rest of the world. And in the process, the CCP said, the governance of the United Nations and other international institutions would be improved.

That’s the polite side of China’s campaign. Beijing has instructed its ambassadors all over the world to raise doubts about the origin of the virus, calling it “the Italian virus,” or the “Japanese virus,” suggesting that it might even have been man-made. In a perverse mirror image of xenophobic anti-China conspiracy theories on the American right, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian suggested the virus came out of an American laboratory. The White House responded with accusations about Chinese cover-ups and incompetence.

He also has tweeted and given speeches claiming that U.S. Army representatives brought the novel coronavirus to Wuhan in October 2019.

“The US has finally acknowledged that among those who had died of the influenza previously were cases of the coronavirus. The true source of the virus was the US!” one commentator said in response to Zhao’s postings. “The US owes the world, especially China, an apology,” another commentator said, and some on social media referred to the “American coronavirus.”

State-run media accused the United States of denigrating China’s fight, while castigating the many genuine failures of U.S. planning and policy execution in the face of the crisis: “They have misused the time China bought for them by blaming China for so-called ‘delays’ during the initial stage of the outbreak. A full month after the beginning of the out-break in China, the US still has not yet equipped itself with sufficient and reliable testing kits, missing the opportunity to identify cases and curbing the spread of the virus. Large public events and rallies are still being held in the US, despite the risk of mass infection.... After accusing China of providing ‘imperfect’ data, the US is being far from transparent.”

White House National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien counterpunched, charging that China’s handling of the initial outbreak in Wuhan “probably cost the world community two months to respond and those two months, if we’d had those [and] been able to sequence the virus and had the cooperation necessary from the Chinese, had a WHO team been on the ground, had a CDC team, which we had offered, been on the ground, I think we could have dramatically curtailed what happened both in China and what’s now happening across the world.”

Similarly, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo consistently refers to “the Wuhan virus,” enraging China. Pompeo also eagerly took up O’Brien’s line of attack, charging that the early cover-up efforts in Wuhan damaged the rest of the world’s ability to prepare, “putting the U.S. behind the curve.” The State Department summoned China’s ambassador to the United States, dressing him down for waging a “blatant” disinformation campaign. Pompeo went further, undermining negotiations over a G7 statement responding to Covid-19 by insisting all official communiques refer to the “Wuhan Virus”—and the president pointedly and repeatedly has called Covid-19 the “China Virus” or “Chinese Virus.”

Trump campaign supporter Charlie Kirk, head of the Koch-funded right-wing advocacy group Turning Point USA, tweeted reference to the “China Virus,” adding that the United States could still contain its spread, “if we can control … our borders.” President Trump piled on that tweet, writing, “Going up fast. We need the Wall more than ever!”

One recent study claims 66 percent of the global burden of Covid-19 would have been eliminated if China had acted faster, closing down Wuhan weeks earlier. But the same study credits China’s eventual actions for preventing a catastrophic pandemic that would have been 67 times worse without them. Nevertheless, a host of conservative talk show pundits and politicians have taken to China-bashing, accusing Beijing of deliberately imperiling the world, and of deceiving the president, thus rationalizing America’s slow response to Covid-19. Both China and the United States have expelled journalists hailing from their rival nation, claiming the reporters spread falsehoods.

President Trump seemed genuinely bewildered when Congress rejected his request for $2.5 billion in emergency funds to fight the epidemic, much of it stripped from prior moneys committed to Ebola preparedness. A bipartisan vote in both houses found the White House request woefully small, authorizing instead a bill funded for $8.3 billion. In remarks to Sean Hannity on Fox News, Trump also seemed to dismiss, yet again, the likely severity of the Covid-19 threat, calling it the “coronaflu.” He observed further that, much like seasonal influenza, the coronavirus would be something that made a few people very sick but for most was so mild that they could go to work, as usual.

Seemingly unable to grasp how monumental the pandemic battle would be, Trump continued to address crowded rallies of supporters and shake hands on the campaign trail. He’s also socialized with Florida Republican Representative Matt Gaetz, who has since been quarantined for coronavirus exposure, and Fábio Wajngarten, communications chief for Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who’s been diagnosed with Covid-19, apparently acquired during a visit to Mar-a-Lago, the president’s Florida retreat.

Nothing seemed capable of shaking Trump’s faith in border closures and travel bans—the core of his Covid-19 control campaign. But the CDC acknowledged that during the first three weeks of airport screening only one potential Covid-19 case was discovered out of 46,016 examined. And two graphics told the tale of America’s vulnerability by mid-March. The first tracks outbreaks all over the world, indicating that the United States was running in tandem with Italy, lagging about 10 days behind the overwhelmed nation.

The second damning comparative chart, produced by the Council on Foreign Relations, tracked the rise of cases in countries with, and without, travel bans, indicating the four fastest-growing epidemics were all in nations that made travel bans the key element of their coronavirus policies—one of them, the United States of America.

Such are the risks incurred by dangerously uninformed demagogues in the rounds of their daily political life. For the rest of us, the stakes of the coronavirus pandemic are much higher. In a closed-door meeting on Capitol Hill in early March, congressional physician Brian Monahan told staffers that roughly a third of all Americans, perhaps up to 150 million, will be infected with the coronavirus this year.

As April approached, some in China’s leadership seemed eager to soften tensions, trying to disclaim prior allegations that Covid-19 was manufactured in a U.S. military laboratory. But real damage has been done to the Sino-American relationship, and it may not be easily reparable.

It is tragic and perverse that animosities between two egotistical leaders and their sycophantic circles of advisers have placed the entire world in grave peril. Trade disputes between Washington and Beijing were already producing widespread global fallout before the emergence of Covid-19.

True, conventional diplomatic initiatives can control some of this damage—but it’s also the case that no reasonable dialogue between the United States and China can transpire unless both sides are willing to start the conversation based on valid science. Neither Beijing nor Washington seems remotely inclined to take on this humbling challenge to the actual legacies of their respective Covid-19 programs. President Donald Trump refuses to grasp scientific principles, on any topic, and openly contradicts his leading public health and scientific research advisers. For his part, President Xi Jinping remains determined to change the conversation regarding the origins of SARS-CoV-2, removing all references to its linkage to Wuhan.

Going forward, there is one hope for humanity, and for the Sino-American relationship: the development of an effective coronavirus vaccine. Several nations, including China and the United States, are racing to create a vaccine, and to push prototypes of one into large clinical trials. With luck, one of those products can stop Covid-19’s spread, without difficult side effects.

But that may well lay the groundwork for additional high-stakes battles. In past global epidemics, such discoveries have led to two terrible outcomes: patent disputes, and a fully unjust distribution of lifesaving innovations worldwide. In 2009, for example, the H1N1 swine flu spread globally in less than six months, but viable vaccines weren’t available for most countries until the epidemic had passed. Poor countries never did receive supplies of the vaccine that were sufficient to put a dent in their outbreaks. Fortunately, the H1N1 virus was relatively benign, and the failure to distribute a global vaccine had no significant mortality outcome.

International agencies are now poised to counter such profit-motive failures in the vaccines markets, drawing their funding mostly from the Gates Foundation and the foreign aid budgets of a handful of wealthy countries. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which grew out of the World Economic Forum, offers financial support for vaccine invention. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, makes bulk purchases of childhood vaccines and helps ensure their distribution in poor countries. The Global Fund underwrites some health system costs for poor countries, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa. Together, they represent a fledgling international infrastructure for global immunization.

But Covid-19 won’t simply disappear if the wealthy world is left to its own devices, manufacturing costly vaccines that are only affordable to fully insured residents of the 30 richest nations on Earth. What we collectively face is the need to execute the largest mass immunization program in world history, deploying teams of vaccinators to every nook and cranny of the planet, rich or poor.

The last time any such gargantuan feat was attempted was following a Soviet and American 1966 call for smallpox eradication, led by WHO. Thousands of vaccinating teams deployed all over the world, eventually in 1977 vanquishing the virus that killed more human beings in the twentieth century than all wars combined. As totemic as smallpox eradication is in the annals of global public health, it was accomplished at a time when three billion fewer people lived on the planet, and many of them lived in countries that conducted routine childhood immunization. This meant that the immunization initiative undertaken from 1966 to 1977 targeted about one billion people.

If an effective Covid-19 vaccine is developed, its targets will include almost eight billion human beings, with nearly three-quarters of a billion living in conditions of extreme poverty, according to World Bank figures. Eliminating the coronavirus scourge will require mobilization of tens of thousands of immunization teams, armed with affordably priced vaccines. It is likely that both China and the United States, based on their initial human tests of candidate vaccines, will lead global manufacturing—and that both countries will face the moral and economic pressures of balancing global needs against company profits.

In the best of all possible worlds, Presidents Xi and Trump can rise to this epochal challenge, and see their way clear to formalize an agreement to execute the largest humanitarian effort in world history to arrest the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. And in that long-shot scenario, we might even see these two power-mad egomaniacs share a Nobel Peace Prize.