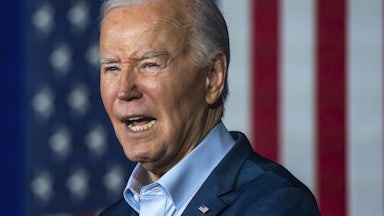

Ten days before Christmas, President Joe Biden’s legislative agenda seems to be imperiled, and the future of his signature childcare, health care, and education package in doubt. Although Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer had previously vowed that the Senate would vote on the $2 trillion bill, known as the Build Back Better Act, before the holiday, it has long seemed that this timeline was way too optimistic. Now, 10 days before Christmas, the delicate balancing act has been wholly upended: The Senate may be close to tabling the Build Back Better Act and cuing up a run at passing voting rights legislation instead.

In a speech on the Senate floor on Wednesday, Schumer struck a more cautious tone than his optimism of previous weeks. “This week, Democrats also continue working on getting the Senate into a position where we can vote on the president’s Build Back Better legislation,” he said.

But Democrats are running up against two hurdles in moving forward with the measure. The first is addressing parliamentary issues with the bill, ensuring that it would be able to pass using budget reconciliation, a complicated process that would allow it to pass without any Republican votes. The second and perhaps more serious challenge is continued skepticism from Senator Joe Manchin, who has raised concerns about the price of the bill, as well as many of its components.

Meanwhile, Senate Democrats are mulling a rules change in an effort to pass voting rights legislation before the end of the year, and Manchin is also at the nexus of this thorny matter. Republicans have already blocked multiple voting rights and elections-reform measures this year using the filibuster. Democrats are currently trying to figure out a way to fulfill Schumer’s promise to “restore the Senate”—that is, make the upper chamber more functional without eliminating the filibuster. A group of moderate Democrats, including Manchin, have engaged in multiple conversations in recent days about a potential rules change to make a filibuster more difficult. If it appears that Democrats are unable to pass the Build Back Better Act now, they may attempt this unexpected end-of-year switcheroo, pivoting their attention to voting rights legislation.

“In terms of time priorities, obviously voting rights has got to be dealt with immediately. I would like to see Build Back Better dealt with as quickly as possible, but if we can’t deal with it right now, it’s far more important that we deal with the voting rights issue,” Senator Bernie Sanders told reporters on Wednesday. The potential bait and switch did not appear to have been cleared with all Democrats, however. Senator Dick Durbin, the majority whip, told reporters on Wednesday that he did not know anything about addressing voting rights before the Build Back Better Act.

Some Democrats argue that it is important to pass voting rights legislation as soon as possible due to the restrictive measures being passed in Republican-led states, not to mention the partisan gerrymandering that is changing the landscape of electoral maps in many red states. Senator Brian Schatz pointed out to reporters that the Senate had effectively created a carve-out to the filibuster to vote on an increase to the debt ceiling this week.

“I think the fact that we just modified the rules for the purpose of raising the debt ceiling, which I support, makes it a little harder to argue that these rules are etched in stone and sacrosanct,” Schatz said. But Democrats were only able to create that exception for the debt limit with support from a sufficient number of Republicans, who are not likely to be as forthcoming on voting rights legislation.

Democrats have not yet reached an agreement on what the rules change would be, so it remains just as uncertain whether they can pass voting rights before the end of the year as whether they can pass the Build Back Better Act. “We’re making progress, but that’s about all I can say,” Senator Tim Kaine told reporters. He later added that whether the Senate would vote on a voting rights bill was “a leadership question.” Senator Jon Tester told The New Republic that the meetings on voting rights have been “all positive” and that conversations would continue. Tester later told reporters that he supported a talking filibuster, requiring senators to be present on the floor and speaking if they want to block a bill.

Manchin has said that he believes any rules changes should have bipartisan support, somewhat narrowing the pool of filibuster reforms that could be enacted. However, comments from Senator Raphael Warnock, a key advocate for passing voting rights legislation, appeared to indicate that the two parties are not close to an agreement on a rules change. “Given the position that they’re taking, that they’ve taken, we’ll keep pushing on them, but the country can’t wait until they decide that they actually want a path forward that embraces all the electorate,” Warnock told reporters on Wednesday.

But the Build Back Better Act also has a time-sensitive element, as it includes a one-year extension of the expanded child tax credit, which is set to expire at the end of the year. If the credit is not extended, Wednesday will mark the last day that families receive a monthly installment of the enhanced credit. The expanded credit for the first time allowed parents too poor to file income taxes to receive it, a provision that will also expire at the end of the month—meaning that millions of children are at risk of slipping below the poverty line or sinking deeper into poverty.

Manchin has previously expressed skepticism of the credit, suggesting it should be further means tested or tied to work requirements. CNN reported on Wednesday that the credit was a major sticking point in discussions with the White House over the Build Back Better Act.

A source familiar with the discussions between Manchin and Biden told The New Republic that Manchin had not told Biden what to include or not include in the Build Back Better Act. But this source noted that the West Virginia senator has been firm in his opinion that the cost of the bill should not exceed $1.75 trillion and that the expanded child tax credit would cost $1.4 trillion over 10 years. (The senator has been consistent in this concern, justifiably worrying that the cost of the Build Back Better Act was only $2 trillion because Democrats said they would only extend most programs for a year or two when they actually meant to make it permanent, a gimmick he referred to as “shell games.”) Manchin also told reporters on Wednesday afternoon that he was “not opposed to the child tax credit” and called a reporter who persisted in questioning him about it “bullshit.”

Several Democrats expressed frustration that the child tax credit may be in jeopardy. “It seems to me the last thing we should be doing with this moment of rising prices is raising taxes on working people in this country, which is what the effective ending of this policy would be,” said Senator Michael Bennet, one of the biggest advocates for the child tax credit. The credit has already contributed to a drop in the child poverty rate and in food insufficiency among families with children. Bennet later told reporters that he had “believed there was a deal” to extend the credit for one year and make full refundability permanent. When asked by The New Republic if he planned on speaking to Manchin, Bennet replied: “I certainly do.”

“It’s not going to be zeroed out,” Senator Sherrod Brown, another staunch supporter of the credit, told reporters. Senator Ron Wyden said that he was looking for a way to pass a standalone bill extending the child tax credit through a procedural maneuver.

“We’re also spending a lot of time looking at what would be necessary to get a fix before the Senate leaves,” Wyden said. But unless Democrats take action to, say, eliminate the filibuster or create a carve-out, they will need support from 10 Republicans to extend the child tax credit, which at the moment seems unlikely.

While it remains to be seen whether the Senate will vote on the Build Back Better Act, voting rights legislation, or some combination of the two, the upper chamber is acting on some of its most critical agenda items. Even as Republicans and at least one Democrat resist increasing social spending, increasing defense spending remains a bipartisan priority. The Senate on Wednesday overwhelmingly approved a $768 billion defense bill for the next fiscal year—roughly half of what the child tax credit would cost over 10 years—increasing the Pentagon’s budget by around $24 billion more than Biden requested.