Bird propaganda is everywhere, once you’re trained to recognize it. Since the Cold War, children have eaten their breakfast cereals with Toucan Sam and spent their after-school hours learning at Big Bird’s oversize feet. Television has streamed into our homes and onto our smartphones under the strutting sign of NBC’s rainbow peacock. Penguins gaze out at us from our bookshelves. Eagles, the government insists, are patriotic symbols of strength and freedom. Duolingo uses an earnest but irritating green owl to engineer our digital behavior and shame us into learning rudimentary Portuguese.

As you catch your breath from this unnerving revelation, you should also know that there is a growing movement online determined to reveal the truth: that none of this is benign, none of it accidental. That Americans are being birdwashed into docility and obedience.

Calling itself Birds Aren’t Real, this group of primarily Gen Z truthers swaps memes and infographics on social media (the official accounts boast more than 800,000 followers on TikTok and 400,000 on Instagram), challenges the powers that be with combative media appearances, and holds rallies across the country. They explain that the U.S. government secretly ran a “mass bird genocide” starting in the late 1950s, replacing the real avian population with sophisticated surveillance-drone look-alikes. Bird-watching now goes both ways.

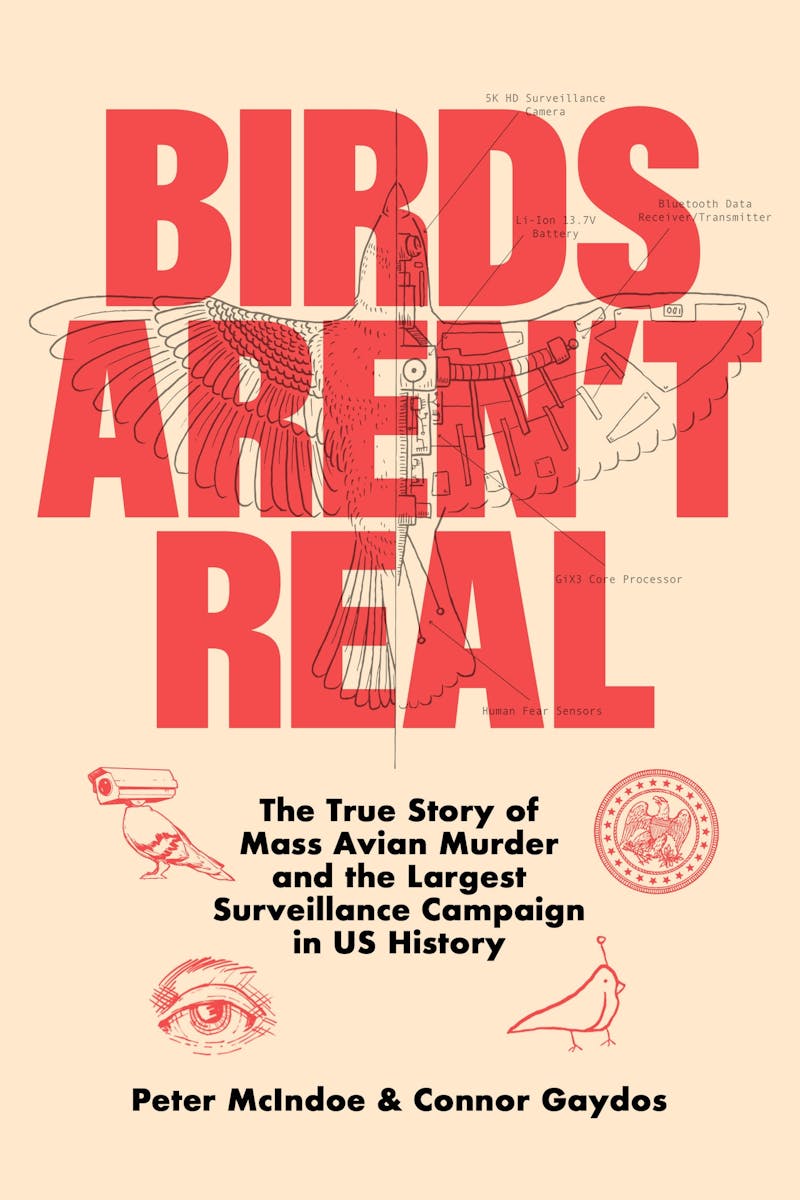

If ever you’ve feared that the internet has become less weird, this should ease your mind. Birds Aren’t Real had its first dose of major mainstream attention in late 2021, thanks to a surreal New York Times feature by Taylor Lorenz. Now, the group’s two leaders, Peter McIndoe and Connor Gaydos, have published their manifesto in book form. Over nearly 300 pages, they reveal how the bird genocide plot was hatched by notorious CIA director Allen Dulles—when he wasn’t spearheading the MK-Ultra mind-control program. Using stolen documents and confidential transcripts, they also show the complicity of presidents from Eisenhower to Biden. Alongside this revisionist American history, the book offers a field guide for recognizing bird-drones in the “wild” as well as instructions for resistance. There’s also a word search (AVICIDE, CIA KILLED JFK).

Know one last thing: It’s not real. Birds Aren’t Real is an elaborate and successful prank. Everyone is in character, from McIndoe and Gaydos down to the TikTokers going off on Thanksgiving (a suspiciously bird-centric holiday) in the comments. Every document in the book is total fiction. I’d even go so far as to say that birds are probably real, after all. But none of this should imply that what the bird truthers are up to isn’t serious or helpful. Our dragon-ridden age needs its wise fools.

Cosplaying the paranoid fringe, Birds Aren’t Real delivers a knowing satire of American conspiratorial thinking in the century of QAnon. Beneath the collegiate humor, however, lies a profound grasp of conspiracism’s psychic appeal, and a valuable provocation. How to best fight false claims and conspiracies online is currently the subject of fierce debate among social and computer scientists, policymakers, even the Supreme Court. (McIndoe has called his faux movement an “experiment in misinformation.”) The rest of us wonder how we can bring our family members and fellow citizens back to reason, dampening the influence of what Richard Hofstadter, some 60 years ago, termed the “angry minds” of American politics. Could it be, as a consequential election looms and violent online fantasies spray into real life, that we are going about it all entirely the wrong way?

Nearly one in five Americans believes, according to a recent poll, that Taylor Swift is an asset of the deep state, her celebrity manufactured by a Pentagon “psyop” meant to help Joe Biden win reelection. This is only the latest conspiratorial spasm from a right-wing media ecosystem that has fully embraced the QAnon creed. The book of QAnon tells us that the government is controlled by a global cabal of satanic pedophiles—mostly elites in Hollywood, finance, and the Democratic Party—who traffic in and molest children for sport, and that Donald Trump has been anointed by God to save the children and punish the powerful. Whether they identify as QAnon supporters or not, millions of Americans believe this to be true, and see themselves as heroic soldiers in a Manichaean struggle of absolute good over fathomless evil.

Against this backdrop, Birds Aren’t Real feels downright old-fashioned, more chemtrails than adrenochrome. For all its baroque social media lunacy, it is paranoid but not violent. It doesn’t ask its followers to murder anyone. (This is a feature that sets QAnon apart from its quainter predecessors.) In many other ways, however, Birds Aren’t Real is the perfect conspiracy theory, built on an astute understanding of how they work and what makes them so compelling. Four qualities are particularly important.

Birds Aren’t Real offers, first of all, a “theory of everything”—a way for people to make sense of the world’s complexity and contradictions, to tie up all the loose ends. The group can explain the JFK assassination (murdered by a hummingbird drone after he challenged Dulles), the U.S. invasion of Vietnam (to secure bauxite, a mineral needed for drone building), the Flight 1549 Hudson River crash (a failed bid to kill secret bird truther Sully Sullenberger with a goose robot), and even why so few of us have ever seen baby pigeons (they emerge from the factories as adults). That you’ve seen so little evidence is merely a sign of how deep the plot goes. Airtight logical systems are created in many conspiracies, like QAnon. They appeal to people who prefer certainty over ambiguity, who see “I don’t know” as a discomforting answer. Psychologists call this the need for cognitive closure, and have found it associated with anxiety, authoritarianism, and conspiratorial thinking.

Much like Covid deniers, bird truthers are also masters of what we might call argument by adjacency. Related credible facts are adduced as proof of wilder claims, offering just enough truth to make you wonder. Do your own research into the bird-genocide plot, for instance, and you’ll find that the United States did spend the Cold War running a range of secret operations, from coups to surveillance of civil rights leaders to attempts at drug-induced brainwashing. Birds Aren’t Real observes that these are “not conspiracy theories, but conspiracy facts,” proving that Washington “does indeed conspire behind the scenes to do insane and illegal things.” It’s widely accepted, too, that we are ensnared in a form of surveillance capitalism in which technology companies closely track our behavior as a means of astronomical profit. And isn’t it suspicious that “animal-free” eggs are now for sale on grocery store shelves? In a world where these things are incontrovertibly true, an elaborate system of secret bird-drone surveillance makes a certain logical sense.

Finally, successful conspiracy theories are able to perform a kind of psychic alchemy for their followers. On the one hand, they drain pleasure from everyday life. Nothing can be innocent; everything is wrapped up in the plot. QAnon supporters pull away from friends and family, convinced that the people they most love have become satanic cultists. Birds Aren’t Real tells you that you can’t enjoy simple joys like nature walks and bird-watching, family Christmases (eating turkey is “ritualized bird worship”), or even your pets. People with birds at home are advised “to calmly pack your things in the middle of the night and leave. Make sure your bird does not see you leave.” Your pet bird never loved you, for it was merely a government drone-robot, but at least now the imminent danger has passed.

In exchange, believers are haloed with heroism. They are recognized as being among the elect and told not only that they have the power to act for truth and justice—but that they have a responsibility to do so. As one ex-QAnon follower told journalist Mike Rothschild for his book The Storm Is Upon Us, believing in “Q makes you feel important and gives you meaning and self-esteem.… You are saving the world when you’re in Q.” McIndoe and Gaydos tap into similar ideas in their bird-drone manifesto, inviting their followers into a fellowship of martyrs and winkingly praising their courage. With the deep state arrayed against bird truthers, their book is “the most dangerous … in the history of literature,” and “you are putting yourself in great danger by reading it.” Ordinary actions are draped with epic significance and hidden danger. “We will never stop pushing,” they theatrically vow. “We will never stop violating community standards.”

In his much-maligned (yet scarcely read) 1992 bestseller, The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama claimed that political and social change was driven primarily not by economic conditions, but psychological motivations. It’s the innate human desire to be recognized, to be seen by other people and institutions as “worthy of respect” and dignity, he wrote, that moves political history—and can always upend even the most stable states. Fukuyama called this drive thymos. Modern conspiracy theories, like QAnon, may satisfy it. It doesn’t hurt that we’ve been conditioned to expect the democratization of power and celebrity by social media: Upload the right video or do some internet sleuthing or make a viral hashtag, and you, too, can shape historical events.

But it’s widespread despair that has made the psychic bargain promised by conspiracies so compelling. As McIndoe has explained, “a lot of people feel like they’re the victims in this tragic story of themselves as the main character. I don’t feel purpose. I don’t have identity. I don’t have people that love me.” By embracing conspiracism, however, “you reposition yourself” from “the victim to the hero.” What the bird truthers understand so well is that paranoiac misinformation cults make people feel not powerless or vulnerable, but valuable. Needed.

McIndoe is not a conspiracy theorist himself. Not really. But his personal biography offers some clues to his performance as well as the serious purpose behind his work. You wouldn’t know it by reading the book, which is written fully in character; the fourth wall remains intact. This is a shame, because the real Peter McIndoe is worth listening to. One thing he knows better than most of us is just how literally, as Don DeLillo observed in his novel White Noise, “the family is the cradle of the world’s misinformation.”

McIndoe, now in his mid-twenties, passed his teenage years in Arkansas under what he has called conditions of “ideological loneliness.” In the conservative religious community that raised him, conspiratorial thinking was rampant: that vaccines contained microchips, that Barack Obama was the Antichrist. McIndoe was homeschooled (he recalls being told that it was to avoid brainwashing by the government), but he grew increasingly skeptical of the paranoid tales around him. His peers saw him as a black sheep and voted him most likely to end up in jail. McIndoe felt that he was “on the fringes of normal society” because he refused to accept their beliefs.

Then he went online. Rifling around on Reddit and YouTube, he was pulled from the far reaches of conspiracism into the mainstream. Incredibly, he found not rabbit holes to fall down, but wide-open landscapes—full of fact-based news and information, populated with different perspectives than the ones swirling around him at home. The internet gave McIndoe his “whole understanding of the world,” and the comforting knowledge that he was not alone in trusting science or seeing the president as human. Finally, he belonged.

He started Birds Aren’t Real by accident in early 2017, while in Memphis. At a women’s march organized to protest Trump’s inauguration, he dashed the infamous three words on a poster as a joke. Someone recorded it and posted it online, the clip went viral among teens in the South, and McIndoe left school to focus on his newfound fake movement. He stepped into character as the group’s public information officer, drawing on his memories of conspiratorial Arkansas. “I used the same cadence, logic, and arguments as those I grew up around,” he observed in a 2023 TED talk, “just with a different theory swapped in.”

Teens and twentysomethings, like McIndoe and the bird truthers, are frequently chastised by policymakers and academics for failing the test of online misinformation—singled out for being apathetic about current events or insufficiently critical of the claims and content they consume. The broader critique is that Gen Zers are, like the millennials before them, too much in their phones, too online, too detached from reality to be fine critical thinkers and good citizens. In fact, young people are more sophisticated and savvy than this grave portrait indicates. But their reactions to this torrent of digital detritus may look unfamiliar or even nihilistic to those of us raised in a slightly more orderly and manageable world.

The explicit purpose of Birds Aren’t Real, McIndoe told The New York Times in 2021, is about “holding a mirror to America in the internet age.” He and his peers have grown up in a world of dopamine hits and deepfakes and endless scrolling, where what happens on social media is just as real as what happens offline. Bird truthing is both satire and a kind of generational catharsis, a therapeutic reaction to the sense of being trapped on platforms that reinforce our worst instincts and watching serious adults descend into madness. Like real conspiracies, Birds Aren’t Real offers people agency in a world fallen to pieces. One organizer has called it “fighting lunacy with lunacy.” McIndoe has evocatively described his performance-art project as building “an igloo in a snowstorm”—creating “shelter out of the same type of material that’s causing the chaos” and providing a space for people to “safely process misinformation” rather than succumbing to it.

Over the past 10 years, it’s become clear that online misinformation (to say nothing of state-sponsored disinformation campaigns) is capable of undoing our shared reality and tipping public life into disarray—from Trumpian lies to QAnon to the Covid infodemic. How to fix it is less obvious. One paradigm puts the onus on government to force social media companies to remove false information from their platforms, or make algorithms less likely to amplify conspiracies. The Supreme Court will soon tell us how directly the government can be involved in content moderation (a ruling is imminent in Murthy v. Missouri), but the failure of government agencies to meaningfully regulate Big Tech firms in the United States means that most experts are focused instead on getting individual people wiser to fake news.

Misinformation experts are currently working out three different approaches. The oldest and most familiar is information literacy. This field focuses on arming citizens with the critical thinking skills they need to identify false or poorly sourced claims, overheated rhetoric, or opinions playing as facts. People are inclined to be rational, in this view, but need the right education and training in order to do so.

More recently, behavioral psychologists have investigated ways of nudging people into thinking more about accuracy and their own biases when consuming information on social media. (Recall how then-Twitter introduced a feature in 2020 that invited users to read articles before resharing them.) This mode assumes that human beings are mostly irrational, but can be tricked into overcoming their own cognitive flaws.

The most novel and promising approach, however, is known as prebunking. Pioneered by Cambridge social psychologist Sander van der Linden, this mode pulls from the metaphor of virality to suggest that people can be inoculated against misinformation. Studies have found that exposing people in controlled ways to false claims can help them acquire “psychological immunity” to misinformation when they confront it next.

Although these modes make different assumptions about human psychology, they have a common understanding of the problem and a shared vision of what success will look like. For the most part, researchers are focused on the interaction between an individual person and a single piece of (mis)information—the moment of critical judgment. And they agree that strengthening people’s rational faculties is the solution, whether we get there through skills education or gentle misdirection or both, by hook or by crook.

As thoughtful as these interventions are, it’s hard not to wonder if they are commensurate with the problem we face—if they reflect the world as it is, in full. One immediate wrinkle is that most people’s experiences with information are not solo but rather intensely social.

In a study I co-wrote last year, for instance, we learned first of all that Gen Zers tend to digest information together with others: in group chats with family and friends, on Reddits and Discord servers, and in the comments sections beneath TikTok and YouTube videos. The value of that information is often social, too. All of us (but especially young people) metabolize information about the world not just because we want to seek the truth, but to know who we are and what we believe in relation to those around us. What this means is that people are often familiar with anti-misinformation tactics, particularly in a classroom or professional setting, but may choose not to deploy them in their daily lives.

Indeed, there’s reason to doubt that greater rationality and more critical thinking will get us back to the world of shared reality we’ve lost. The sociologist and internet researcher Francesca Tripodi has brilliantly shown that religious conservatives who believe in false claims and conspiracies consume a wide variety of news sources and apply close critical habits of textual analysis to what they read—tactics recommended by academic experts. Purveyors of Covid misinformation, too, as MIT professor Crystal Lee and her co-authors have revealed, are using data visualization tools and the trappings of scientific analysis to lead people away from mainstream public health. QAnon itself is the twisted embodiment of this tendency, a cult movement built by citizen-researchers (known as “bakers”) who are doing nothing more than “just asking questions.” As Richard Hofstadter had it in the mid-1960s, facing the conspiratorial Goldwaterian right, the “paranoid mind” is “nothing if not scholarly in technique.” Rationality’s greatest weakness, perhaps, is that it is a procedure more than a commitment. Teaching people critical thinking and rational argument is the easy part; the less comfortable and more difficult work involves creating social and political consensus, establishing (and defending) the shared values that reason is meant to serve.

McIndoe and his Dadaist troupe of bird truthers are raising this deeper and more troubling challenge, inviting us to wonder if the crusade against misinformation—focusing on truth and accuracy and critical reasoning—hasn’t somehow missed the point. What’s appealing about Birds Aren’t Real and QAnon, McIndoe has suggested, isn’t the promise of truth so much as the feeling of community. “We have to consider that conspiracy theorists are not just joining these groups for no reason,” he argued last year. “They’re getting rewards out of these, things that we are all looking for.” Identity, purpose, meaning, a sense of agency and recognition and solidarity. The rise of conspiracism and misinformation is not a crisis of belief, observe the bird truthers, but belonging.

As the philosopher and historian Justin Smith-Ruiu has written, “it is irrational to seek to eliminate irrationality.” We’re determined to do it anyhow. This is the founding fiction of modern liberalism as well as its tragic flaw. We know that human beings are not rational in reality, but wouldn’t it be better if they were? In every national election cycle since the explosion of the Tea Party, Democratic leaders and voters alike have found this to be the most natural and comfortable response to the extreme right. It’s satisfying to believe that the right-wing “fever” will eventually break, that being the adults in the room is enough, that being a good citizen means erasing our feelings and returning to a lost era of rational deliberation. But it’s all a mirage, and not a helpful one. In fact, we have always been, as DeLillo had it, “fragile creatures surrounded by a world of hostile facts,” doing our level best to reason together about what we feel most strongly.