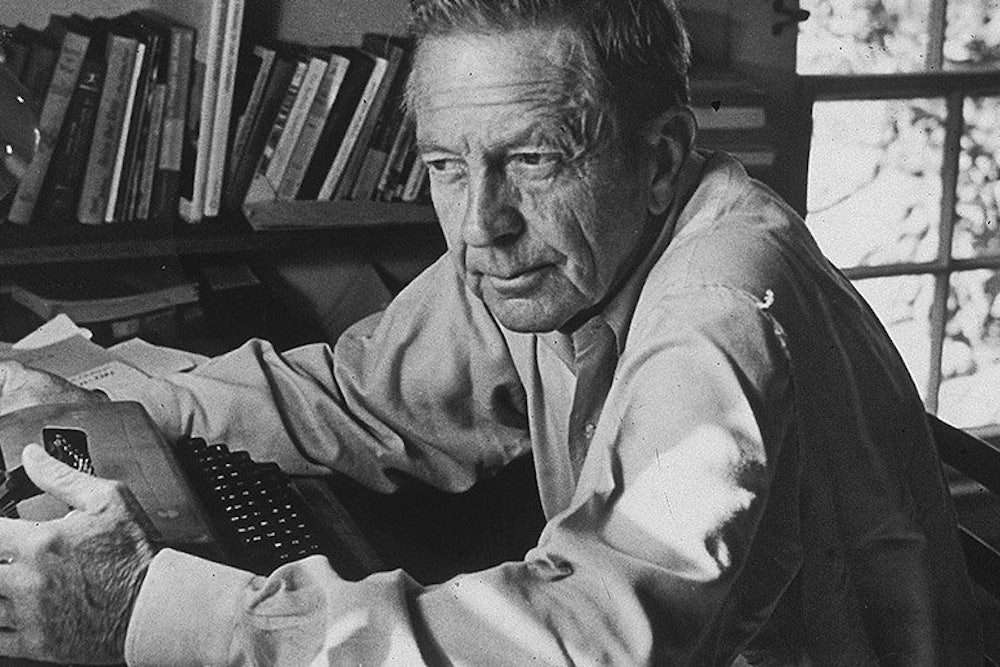

The Journals of John Cheever, published as a big and glossy book, make a rather different impression than the journal excerpts published in three two-part batches in The New Yorker over the last 16 months. In the magazine’s pages, they seemed a gesture partly sentimental, a gesture that reminded its faithful readers of how luminously and jauntily Cheever’s fiction had filled those same columns in bygone decades. The journals were a resurrection of sorts, and for all their fragmentariness and disconcerting emotional nakedness they shone with an ardor, an easy largeness, a swift precision that no living contributor to these columns could quite muster. No sullen minimalism or intellectual coquetry here. “How the man could write!” said we to ourselves, as the discrete paragraphs, chosen by unexplained editorial fiat, jogged from a marvelously evoked landscape to an enigmatic marital spat to a Saturday night suburban debauch to a Cheeveresque Sunday morning:

To church: the second Sunday in Lent. From the bunk president’s wife behind me drifted the smell of camphor from her furs, and the stales of her breath, as she sang, “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost.” ... The rector has a plain mind. If it has any charms, they are the charms of plainness. Through inheritance and cultivation he has reached an impermeable homeliness. His mind and his face are one. He spoke of the impressive historical documentation of Christ’s birth, miracles, and death. The church is meant to evoke rural England. The summoning bells, the late-winter sunlight, the lancet windows, the hand-cut stone. But these are fragments of a real past. World without end, I murmur, shutting my eyes. Amen. But I seem to stand outside the realm of God’s mercy.

The Cheever prose was back, and thrilling; and thrilling, too, was the scandalous frankness of his revelations, confided in many disconsolate moods to his journal, of severe marital discontent, drastic alcoholism, and repressed homosexuality. In a book of nearly 400 pages, however, the disjointedness, presented in such bulk and without a single clarifying note, begins to frazzle the brain, and the circularity of Cheever’s emotions to depress the spirit. Disjointedness is to be expected in a magazine, and conclusiveness is not to be expected in The New Yorker, but in a book we begin to ask where we are and where we are going.

An editorial decision has been made to present the cream of the journals—one twentieth of their bulk, we are told in an afterword by the editor, Robert Gottlieb—as an extended prose poem, as unannotated emanations from deep within the quiet desperation of a modern American male. Perhaps this was the only editorial decision that could have been made, given the determination to expose the journals at all, less than ten years after Cheever’s death. Many living are mentioned, often indecorously, and must be protected. The dates and locales of these notations, even if knowable, would not add much, though it is confusing to have a writer suddenly in Russia or Iowa or Boston with no explanation of how he got there. Lovers come and go so mysteriously in these notations that we are not always certain of even their sex. Is the “M.” of page 86, dining with Cheever at the Century Club in 1957, the same “M.” as on page 346, sharing with Cheever “a motel room of unusual squalor” in 1978? Certain books and stories can be glimpsed as they go by, in the process of creation, but literary matters are among the least of Cheever’s problems, as the journals have it. We are at sea, amid waves of alcohol, gloom, domestic tension, and radiance from the natural world.

A journal, even when cut to 5 percent of its bulk, reflects real time, where we can experience how sluggishly our human adventure unravels and how unprone people are to change. In a novel, Cheever’s alcoholism would have been introduced, dramatized in a scene or two, and brought to a crisis in which either it or he would have been vanquished. In these journals, the decades of heavy drinking, of hangovers and self-rebukes and increasingly ominous physical and mental symptoms, just drag on. His life is measured out in belts, or “scoops.” On a page from 1968, he describes his preparations for an amorous tryst:

Two scoops for the train, a scoop at the Billmore, a scoop upstairs, one down—five as well as a bottle of wine with lunch and brandy afterward. We rip off our clothes and spend three or four lovely hours together moving from the sofa to the floor and back to the sofa again. I don’t throw a proper hump, which disconcerts no one.

—or would have surprised, he might have added, no medical expert. It was a wonder he could ambulate, let alone copulate. On the next page, be makes a stab at bringing his drinking and his writing into meaningful relation:

I must convince myself that writing is not for a man of my disposition, a self-destructive vocation. I hope and think it is not, but I am not genuinely sure. It has given me money and renown, but I suspect that it may have something to do with my drinking habits. The excitement of alcohol and the excitement of fantasy are very similar.

In this same year he rereads two old journals and comments:

High spirits and weather reports recede into the background, and what emerges are two astonishing contests, one with alcohol and one with my wife. With alcohol, I record my failures, but the number of mornings (over the last ten years) when I’ve sneaked drinks in the pantry is appalling.

Any connection between his besottedness and his wife’s physical and emotional rejections is dimly descried: “Mary is depressed, although my addiction to gin may have something to do with her low spirits.” At one moment, “Mary talks as if she had a cold, and when I ask if she has she says she’s breathing through her mouth because I smell so horrible.” He goes on rather primly, “I seem to suffer from that degree of sensibility that crushes a man’s sense of humor.” Again and again in these lachrymose journals, he is innocently wounded:

In the afternoon mail there is a letter saying that two pieces have been bought. I am jubilant, but when I speak the good tidings to Mary she asks, oh, so thinly, “I don’t suppose they bothered to enclose any checks?” I think this is piss, plain piss, and I shout, “What in hell do you expect? In three weeks I made five thousand, revise a novel, and do the housework, the cooking, and the gardening, and when it all turns out successfully you say, ‘I don’t suppose they bothered to include any checks.’” Her voice is more in the treble than ever when she says, “I never seem able to say the right thing, do I?”

Granted, Mary Cheever, with a fine mind of her own and a formidable father, may not have been easy to impress, but what she had to cope with in the post-cocktail hour seems safely out of the diarist’s line of vision. “She hates me much of the time, but naturally I can’t understand why anyone should hate me.” Her adverse moods baffle him: “I don’t understand these sea changes. Although I have been studying them for twenty-five years.”

His contest with alcohol similarly remains a standoff. In 1959 he observes, “Year after year I read in here that I am drinking too much, and there can be no doubt of the fact that this is progressive. I waste no more days. I suffer deeper pangs of guilt. I wake up at three in the morning with the feelings of a temperance worker.” In 1971, still drinking, he notes. “The situation is, among other things, repetitious.”

Nor does he find much change in his work. As early as 1952 he writes:

As a part of moving I have had to go through some old manuscripts and I have been disheartened to see that my style, fifteen years ago, was competent and clear and that the improvements on it are superficial. I fail to see any signs of maturity, of increased penetration; I fail to see any deepening of my grasp. I was always in love. I was always happy to scythe a field and swim in a cold lake and put on clean clothes.

Nearly twenty years later, with some marvelous fiction to his credit, he tells his journal, “I’ve never much liked my work.” He thought enough of an adverse remark of his daughter’s to record it: “During dinner, Susie says, ‘You have two strings to play. One is the history of the family, the other is your childlike sense of wonder. Both of them are broken.’ We quarrel. She cries. I feel sick.”

In 1970, after the disappointing reception of the rather punchy Bullet Park, an entry begins with the unforgettable cry, “Whatever happened to Johnny Cheever? Did he leave his typewriter out in the rain?” His perversely contented stuckness, as he rotates in a mire of drink and marital discontent, varied by rather forced spurts of child-cherishing and nature-worship but gradually deepening into phobia, artistic impasse, and vicious behavior, should be overwhelming, and it does tax our patience. But in fact even at his lowest ebb Cheever can write like an angel and startle us with offhand flashes of unblinkered acumen.

And there is, beneath the apparently futile churning of these jottings to himself, a story, which we know not from any editorial guidance in reading the journal excerpts but from the biographies by Susan Cheever and Scott Donaldson and his letters as edited by his son Ben. Cheever did, in the spring of 1975, stop drinking. The novel he then wrote, Falconer, and the handsome volume of Collected Stories that he allowed Gottlieb to assemble and to publish, won him the greatest financial and critical success of his life. At the same time, he came out of the closet, and the (mostly) suppressed homosexual urges so darkly alluded to in the earlier journals blossomed into lewd romps, mostly with “M.,” recorded as frankly and joyfully as a psychotherapist could wish: “When we met here, not long ago, we sped into the nearest bedroom, unbuckled each other’s trousers, groped for our cocks in each other’s underwear, and drank each other’s spit. I came twice, once down his throat, and I think this is the best orgasm I have had in a year.”

For those of us who faithfully followed Cheever’s fiction, an oblique announcement of this breakthrough appeared in a short story, “The Leaves, the Lion-Fish, and the Bear,” published in the November 1974 issue of Esquire but never collected in hardcover. Its string of feebly connected episodes included the adventure of two married men, Larry Estabrook and Roland Stark, who are caught overnight in a motel near Denver by a snowstorm; they drink, get down to their underwear, do away with the underwear, make love, and feel great about it next morning. The writer strives mightily to bring gay sex within the bounds of his accustomed moral universe:

The ungainliness of two grown, drunken, naked men in one another’s arms was manifest, but Estabrook felt that he looked onto some revelation of how lonely and unnatural man is and how bitter, deep, and well concealed in his disappointments.

Estabrook knew he had done that which he should not have done, but he felt no remorse—felt instead a kind of joy seeing this much of himself and another… When he returned home at the end of the week, his wife looked as lovely as ever—lovelier—and lovely were the landscapes he beheld.

On the long-stormy marital front, a relative peace set in: The alcoholic cure entailed his return to his house in Ossining, where Mary ministered to Cheever as the infirmities of old age descended upon his hard-used body and where she resigned herself not only to awareness of her husband’s bisexuality but the frequent attendance of his chief homosexual lover, the loyal “M.”—identified as Max Zimmer in Scott Donaldson’s biography. Cheever died at home, surrounded by his family, a few weeks after having been “brought to climax” in his bathroom by this lover, while carpenters were building a studio for Mary: “Desperately ill as he was, Cheever got out of bed and into the bathroom, where, protected from the possible view of the carpenters, he was brought to climax.” “Adiós,” John said when Max left. “Adiós.”

This sunset saga, in which selfishness and selflessness, pathos and pride inscrutably mingle, exists in the journals, as edited, in only the vaguest way. The break with drink, which involved an impulsive night from his teaching post at Boston University that he could not afterward remember, is signaled by the abrupt entry, “On Valium for two days running, and I do feel very peculiar, but it’s better, God knows, than sauce.” The entry before that on the page, presumably composed as Cheever was hitting bottom, is yet one of the most evocative and complex, with its backward and forward motions:

And I think of L. in the morning, the lovely unfreshness of her skin. It was the light scent of a young woman who has made love and slept through one more night of her life ... but in our nearness I am keenly aware of the totality of our alienation. I really know nothing about her. We have told each other the stories of our lives—meals, summer vacations, lovers, trips, clothing, and yet if she stood at a crossroads I would have no idea of the way she would take.

It is in loving her that I feel mostly our strangeness.

After he sobers up, a certain acerbity appears in his prose: “Reading Henry Adams on the Civil War. I find him distastefully enigmatic. I find him highly unsympathetic, in spite of the fact that we breathed the same air.” He takes the train up the Hudson to Saratoga and Yaddo, nostalgically thinks back to how he would sneak into the toilet with his flask and says, “Alcohol at least gave me the illusion of being grounded.” The alcohol, the suppressed homosexuality, the unharmonious wife perhaps made up the “knot” in himself, “some hardshell and insoluble element” that has “functioned creatively, has made of my life a web of tensions.” A true artist, he feared above the ruin of his life the loss of his creativity.

And, for whatever reason, the best and indispensable John Cheever was written when all his conflicts were unresolved, in those parched morning hours stolen from the day’s inebriation and the night’s fretful longings. His last superb stories were “The Ocean” and “The Swimmer” from the early '60s; his best novel was the first, The Wapshot Chronicle of 1953. Falconer, although a brave leap into themes hitherto sublimated—chemical addiction, homosexual love, fratricide, captivity—fails to lift its burden of bizarrerie; I myself prefer to it his last, slim fable. Oh What a Paradise It Seems, and I was struck, reading these journals, by how deeply Cheever, like his elderly hero in that tale, Lemuel Sears, cherished ice skating. Ice skating was his exercise, his Wordsworthian hike, his rendezvous with sky and water, his connection with elemental purity and the awesome depths above and below, while he clicked and glided along, in smooth quick strokes (I imagine) like those of his prose.

Saul Bellow is the contemporary writer he mentions most often, with affection (“He is my brother”) and admiration: “Read Saul. The wonderfully controlled chop of his sentences. I read him lightly, because I don’t want to get his cadence mixed up with mine.” As some confuse traffic noise with a babbling brook; Cheever’s sentences dash and purl with a headlong opalescence:

Snow lies under the apple trees. We picked very few of the apples, enough for jelly, and now the remaining fruit, withered and golden, lies on the white snow. It seems to be what I expected to see, what I had hoped for, what I remembered. Sanding the driveway with my son, I see, from the top of the hill, the color of the sky and what a paradise it seems to be this morning—the sky sapphire, a show of clouds, the sense of the world in these, its shortest days, as cornered.

His metaphors spring startlingly from a settled, instinctive reading of natural signals. Of a face: “A broad, Irish face, florid with drink. The large teeth, colored unevenly like maize. Long, dark lashes, and what must have been fine blue eyes, all their persuasiveness lost in rheum.” Of a room: “His office is furnished with those modest antiques you find in small hotels. His desk, or some part of it, may have come into the world as a spinet.” A sky: “It is one of those days when the massiveness of the clouds, travelling in what appear to be a northerly direction, gives one the feeling of a military evacuation, a hastening, a change in campaign maneuvers.” A night: “The cold air makes the dog seem to bark into a barrel. Bright stars, house lights, rubbish fires.”

One wishes to quote on and on, erecting a glowing verbal shield against the dismaying personal revelations of these journals. Rarely has a gifted and creative life seemed sadder. His loneliness is irreducible, and lifelong:

And walking back from the river I remember the galling loneliness of my adolescence, from which I do not seem to have completely escaped. It is the sense of the voyeur, the lonely, lonely boy with no role in life but to peer in at the lighted windows of other people’s contentment and vitality. It seems comical—farcical—that, having been treated so generously, I should be struck with this image of a kid in the rain walking along the road shoulders of East Milton.

He was a New Englander, and kept a Puritan ruthlessness toward himself. His journals, though used partly as workbooks for his fiction and partly as therapy (“Rows and misunderstandings, and I put them down with the hope of clearing my head”), primarily record his spiritual transactions with that God whose Episcopalian manifestation, though faithfully visited on Sunday mornings, remained discreetly hidden behind the minister’s manner and the bank president’s wife’s camphorous furs. Cheever’s God was a jealous God, manifest in frequently used words like “obscene” and “unspeakable crime” and the “venereal dusk” that enwraps one of the writer’s last fictional alter egos, the old poet Asa Bascomb in “The World of Apples.” Though of a religious disposition, Cheever had no theology in which to frame and shelter his frailty; he had only inflamed, otherworldly sensations of debasement and exaltation. Perry Miller, in his anthology The American Puritans, tells us, “Almost every Puritan kept a diary, not so much because he was infatuated with himself but because he needed a strict account of God’s dealings with him. ... If he himself could not get the benefit of the final reckoning, then his children could.”

One hopes that Cheever’s three children have indeed benefited. Like Noah’s, they have gazed upon their father naked. Ben, the older son, has already edited, with helpful explanatory notes, a book of his lather’s letters, and in a brief and engagingly honest introduction to the Journals describes how, while alive, Cheever offered him a volume of the journals to read:

I told him I liked it.

He said he thought that the journals could not be published until after his death.

I agreed. The he said that their publication might be difficult for the rest of the family.

I said that I thought that we could take it.

Though Ben expresses surprise at how little he appears in the journals, he and his younger brother figure benignly, as innocents who distract Cheever from his dreadful cafarde. Their older sibling Susan appears with a touch of menace, and their mother takes a brutal drubbing, as a romanticized love object who fails to fill her husband’s bottomless needs:

Mary says that my presence is repressive; she cannot express herself, she cannot speak the truth. I ask her what it is that she wants to say and she says. “Nothing,” but what appears in some back recess of my mind is the fear that she will accuse me of being queer … I feel that she does not love me, that she does not even imagine a time when she might.

Ben’s introduction compliments Mary on her courage in letting these journals be published; some might construe it as a long-forbearing wife’s revenge.

To speak personally, this old acquaintance and longtime admirer of Cheever’s had to battle, while reading these Journals, with the impulse to close his eyes. They tell me more about Cheever’s lusts and failures and self-humiliations and crushing sense of shame and despond than I can easily reconcile with my memories of the sprightly, debonair, gracious man, often seen on the arm of his pretty, witty wife. His confessions posthumously administer a Christian lesson in the dark gulf between outward appearance and inward condition: they present, with an almost unbearable fullness, a post-Adamic man, an unreconciled bundle of cravings and complaints, whose consolations—the glory of the sky, the company of his young sons—have the ring of hollow cheer in the vastness of his dissatisfaction. Comparatively, the journals of Kierkegaard and Emerson are complacent and generalizing. And Cheever’s journals make much of his fiction seem timid, arch, and falsely buoyant. (Not that the journals don’t hold fiction; as Cheever’s letter showed, he was an inveterate embroiderer, who would not only bend but break the truth to round out a story.)

Alfred Kazin shrewdly wrote (in Bright Book of Life), “My deepest feeling about Cheever is that his marvelous brightness is an effort to cheer himself up.” In the light of the journals, we can be grateful for the effort. Passages here, in their unstructured emotion, reach higher and certainly descend lower than anything in the fiction, but it is the repute of his fiction that will determine if, sometime in the next century, a scholarly edition of the complete journals, as has been done for Hawthorne’s notebooks, will seem warranted. It would be nice to have names and locations filled in, and a soothing undercurrent of footnotes. A leavening of duller, more dutiful daily entries might relieve the superheated, rather hellish impression this selection makes. For now, we have a literary event, a spectacular splash of bile and melancholy, clean style and magical impressionability.