Painters have long attracted film-makers for reasons too obvious to explore. Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Gogh, Michelangelo are only a few who have served their workaday turn on the screen. Now comes a considerable difference, itself in the hands of an eminent artist.

Lech Majewski is a Polish film, theater, and opera director recognized widely for his startling and enriching imagination. He is much taken with the paintings of Pieter Bruegel, and his film The Mill and the Cross is his response to two Bruegel gems. But Majewski doesn’t want to dramatize Bruegel’s struggles as an artist or as a citizen or as a lover or in any of the guises in which painters have come to us on film. He wants us to understand how those paintings came into being. In fact, for the first twenty minutes or so of this picture, we may feel we are in the wrong theater: we see nothing of the painter.

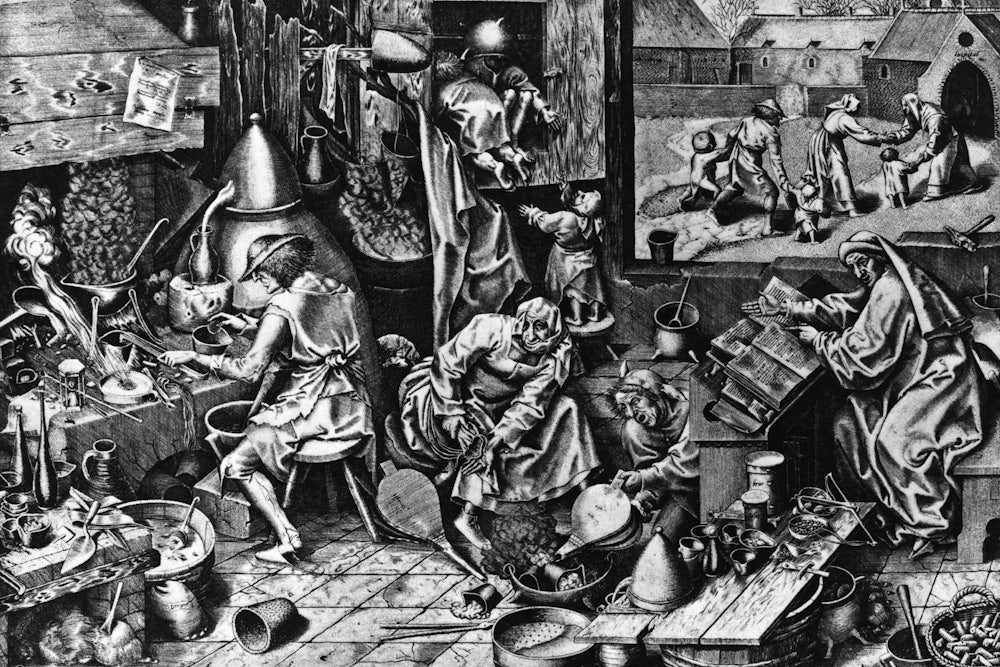

We are in Flanders on a morning in 1564. That is all. In this wide landscape we see people tumbling out of bed, children tossing and squabbling, breakfast being eaten, bread blessed. To demonstrate that we are not dreaming, we are then shown the cruelty of the Spanish occupying forces and the dictatorial clergy. We are beholding a world unrolled before us.

Only then do we see Bruegel himself, sketching a bit, then conversing with a nobleman friend. The two men are played respectively by the German actor Rutger Hauer and the English actor Michael York, but they have very little to say in the film. Neither does Charlotte Rampling, who plays the Virgin Mary, or a person so designated for Bruegel’s purposes. All the dialogue is in English, and there isn’t much.

Another Majewski touch places us in a transition state between art and life. Huge vistas are painted backdrops, subtly done. So we see Flanders as it actually was, marvelously articulated, in the foreground, and we also see it as recreated by Majewski—simultaneously.

The two Bruegel canvases of his concern are The Mill and The Way to Calvary. The first is a striking fantasy. A large mill, whose insides are the film’s opening shots, has been built on top of a tower-like cliff. Of course it could never really exist: how could it have been built, and why? What farmer could bring his wheat there? But Bruegel liked the idea and made the picture; and Majewski furthered the joke by opening his film with close-ups of the mill’s giant wooden mechanisms.

But the major work of interest is The Way to Calvary, which has more than five hundred figures in it, differently occupied as Jesus makes his way with the cross. Bruegel is concerned with the world that Jesus is passing, as seen through these people: their vastly different occupations as he passes unnoticed are what seems the truth of the matter (though of course there are some who know what is going on). It is not a huge canvas, considering its population. We see it in a museum at the end, next to The Tower of Babel.

The film persuades us that, at least as minor onlookers, we have experienced a moment of creation. While it was transpiring, we saw the artist doodling. (In some frozen shots one figure moved naughtily in the background.) We almost feel that we ourselves have accomplished something just by being around while Bruegel doodled.

A particular word must be said about the clothes. Deliberately I use that word rather than costumes. In many a film we have been almost inebriated with costume splendor. Here the clothes designed by Dorota Roqueplo bring realities of existence with them. This is what these people wore and how they lived.

THE CAREER of Sam Shepard is a romance, except that no one would dare write it. What? A man who is both one of the most valuable American playwrights and a magnetic film star? Other playwrights have acted and other actors have written, but none has excelled in both arts as Shepard has done. His plays have won the expected prizes and have been performed around the world: his performances, as in Days of Heaven and Fool for Love (this from his own play), are there to prove themselves. And what caps the romance is the ease with which he takes it all. In the long view, he seems to have viewed his life as just another life, which happened to take this shape.

Now the romance goes further. A Spanish director named Mateo Gil offered Shepard the lead in a heroic-style Western, and Shepard took the chance to enlarge the aura. Blackthorn furthers Western mythology in two ways, both in its script (by Miguel Barros) and in the way it was made.

In this tale Blackthorn is the name adopted by Butch Cassidy, who did not die in 1908, as we all thought, but has led a quiet life in the Bolivian Andes, raising horses. Twenty years later he feels homesick, sells out, and starts home. On the way he meets and gets involved with a young Spaniard who has stolen some money and is being pursued. To say that complications follow, including some flashbacks to the original story, is to minimalize. Toward the end a detective appears (played by the staunch Stephen Rea) who has always thought that Cassidy is still alive and is considered mad.

This story, parboiled out of one of the most memorable Westerns, is supported all the way by Gil’s directing. He says that he loves Westerns, and we cannot doubt it. There are all the beloved shots: the campfire on the edge of a vast shadowy plain, the horizon shot of a man riding along a distant ridge, the close-up of a pistol just as it is about to fire, the posse thundering over a hill toward us. These shots certify the genre.

Shepard himself takes it further. Gray-bearded Blackthorn-Cassidy is a Western epitome—taciturn, clever, competent. Shepard seems to be enjoying it as he goes. That he is consciously extending the romance of his life through this romance of the Western doesn’t seem unlikely. In any case, the sheer impossibility of there ever having been a Sam Shepard still puts him in a unique light.

FAMILY-PROBLEM pictures are of two sorts. The common problem sort, if it is any good, invokes at least a hint of universality. The other sort, with an unusual, possibly dangerous problem, reminds us of risks, some of which we didn’t even quite know we were avoiding.

Such of the second sort is a French film called I’m Glad My Mother Is Alive, the story of an adopted son called Thomas. Through his earlier years and adolescence, he is eager to find and meet his birth mother. He and his younger brother have been taken in by a caring middle-class family and generally enjoy themselves, but he has this burning in him to find his mother, which his adoptive parents do nothing about.

The first hint of roilings in the boy comes early. When he is about twelve, he and family go to a beach resort and there is the usual fuss and lotioning. Soon he and his affectionate (adoptive) father are far out, swimming together, and Thomas plays a trick on his father, frightening him. It is a quasi-vicious action, and Thomas is revealed to be darker than he usually looks.

Time passes cinematically enough. Thomas is now a twenty-year-old garage mechanic. By various means he tracks down his actual mother, named Julie, in a Paris district not far away. She is still a young woman—she was seventeen when she had him—who has been somewhat flexible in her personal life. She now has still another child but no husband.

Thomas and she respond to each other, curious about each other. He even gets a job in her neighborhood so that he can crash with her. Then, inevitably, comes the core of the film: the conflict between the fact that she is an attractive woman in her late thirties and that he is her son.

Not many young men are actually put in this situation, but the duality in a youth’s mother has not escaped many youths. (The names of Oedipus and Jocasta float near, the latter especially. I have long suspected that she had some inkling that Oedipus—wounded feet, right age, and all—may have been her lost son.) Julie has different complications because she knows who Thomas is and is in her own way riven.

The situation works out, not painlessly, but the longer it continues, the more it seems in some way pertinent to the viewer—not in the literal experience, but in the dramatization of remembered visits to the subconscious, in essence if not detail, here acted out before us. Sophie Cattani as Julie takes us with her over several borders, and Vincent Rottiers as the latter-day Thomas is complete in his inchoate anger at fate.

A crowning fact: This film was made by Claude and Nathan Miller, who are father and son.

Stanley Kauffmann is the film critic for The New Republic. This article originally ran in the November 3, 2011, issue of the magazine.