All dictators, from Creon onwards, are victims. --Gabriel García Márquez

I.

Many years later, in the course of writing his memoirs, Gabriel García Márquez was to remember that distant afternoon in Aracataca, in Colombia, when his grandfather set a dictionary in his lap and said, "Not only does this book know everything, it’s the only one that’s never wrong." The boy asked, "How many words are in it?" "All of them," his grandfather replied.

Anywhere in the world, if a grandfather presents his grandson with a dictionary, he is giving him a great instrument of knowledge; but Colombia was not just anywhere. It was a republic of grammarians. During the youth of García Márquez’s grandfather, Colonel Nicolás Márquez Mejía, who was born in 1864 and died in 1936, a number of presidents and government ministers—almost all of them lawyers from the conservative camp—published dictionaries, language textbooks, and treatises (in prose and verse) on orthology, orthography, philology, lexicography, meter, prosody, and Castilian grammar. Malcolm Deas, a scholar of Colombian history who has studied this singular phenomenon, claims that the obsession with language that was expressed by the cultivation of these sciences—their practitioners, Deas notes, insisted on calling them "sciences"—had its origin in the urge for continuity with the cultural heritage of Spain. By claiming "Spain’s eternal presence in the language," Colombians sought to possess its traditions, its history, its classic authors, its Latin roots. This appropriation, preceded by the foundation in 1871 of the Colombian Academy of Language, the first offshoot in America of the Royal Spanish Academy, was one of the keys to the long period of conservative hegemony—it lasted from 1886 to 1930—in Colombian political history.

García Márquez’s grandfather is a prominent figure in the writer’s early novels, and he was no stranger to this politico-grammatical history. Colonel Nicolás Márquez Mejía fought in the ranks of the legendary Liberal general Rafael Uribe Uribe (1859–1914), one of the few caudillos in Colombian history. His story in turn inspired the character of Colonel Aureliano Buendía in One Hundred Years of Solitude. A tireless and hapless combatant in three civil wars, Uribe Uribe was also a diligent grammarian and a soldier in the civic battles between conservatives and liberals. During one of his stays in prison he translated Herbert Spencer, and in 1887 he wrote the Diccionario abreviado de galicismos, provincialismos y correcciones de lenguaje, or Abbreviated Dictionary of Gallicisms, Provincialisms, and Proper Usage, which seems to have been a moderate success.

In 1896 the general stood alone in Parliament against sixty conservative senators. Finally the crushing majority left him no choice but—in his own words—to "give voice to the cannons." Uribe Uribe was the protagonist of the bloody Thousand Days War in 1899–1902, which ended with the signing of the Peace of Neerlandia. The signing was witnessed by Colonel Márquez, who, years later, would receive his former general at the family home in Aracataca, near the scene of the events. Uribe Uribe was assassinated in 1914. Two decades later, his lieutenant presented his eldest grandson not with a sword or a pistol, but with a dictionary. This tome that anywhere else would be an instrument of knowledge was, in Colombia, an instrument of power.

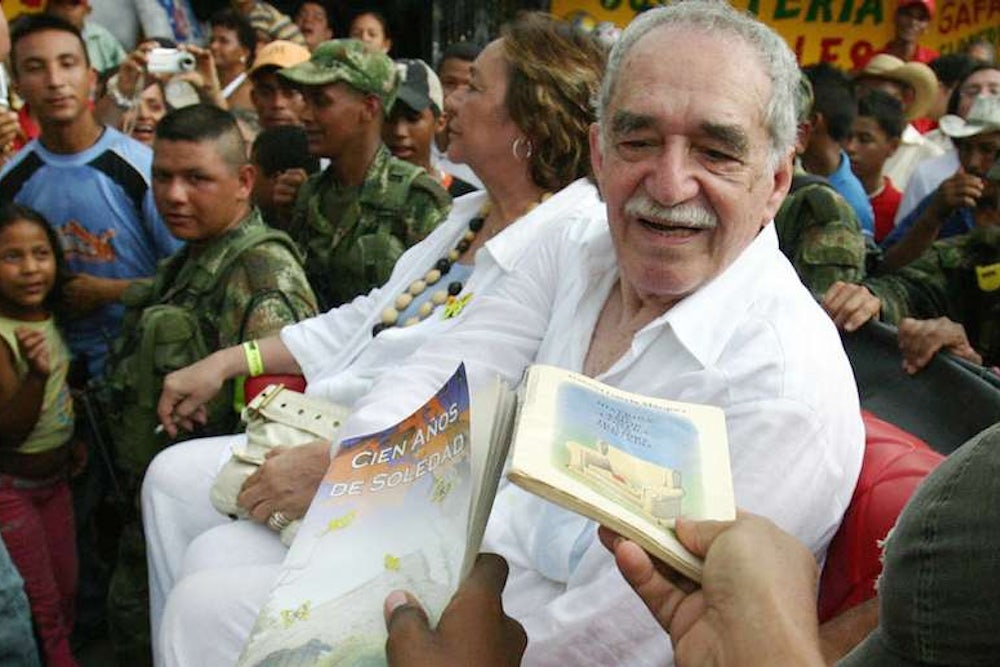

Power would indeed come to García Márquez through the literary arts, but not in his wildest tropical dreams could Colonel Márquez have imagined the prodigious ars combinatoria that his grandson—whom he called "my little Napoleon"—would apply to that dictionary, the "almost two thousand big, crowded pages, beautifully illustrated" that "Gabito" set out to read "in alphabetical order, with little understanding." García Márquez won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982, and his most important novels have been translated into many languages. With their extraordinary force of storytelling, their poetic charm, their prose so flexible and rich that at moments it actually seems to contain all the words in the dictionary, these books are read everywhere, and rightly. His hometown is the site of literary pilgrimages. In Cartagena de Indias, the walled port city where the young reporter García Márquez endured years of hardship, the taxi drivers point out the "Prize House," one of several that "Gabo" owns in cities around the world. The fond nickname reflects the popular sympathy that he inspires.

In 1996, García Márquez settled an old score in Colombian history, heading a small revolution against the dictatorship of dictionaries. To the horror of the Royal Spanish Academy and its American counterparts gathered in Zacatecas, Mexico, the celebrated author—lord and master of "Spain’s eternal presence in the language"—declared himself in favor of the abolition of spelling. The snub was the final victory of liberal Colombian radicalism over conservative grammatical hegemony. The ghosts of General Uribe Uribe and Colonel Márquez smiled in satisfaction.

And Fidel Castro smiled, too. On his seventieth birthday he received from García Márquez the most "fascinating" of gifts, a "real jewel": a dictionary. "I write so my friends will love me," García Márquez has said repeatedly. One of those friends is the dictator of Cuba. In Latin American history, no bond between pen and scepter has been as strong, as intimate, as enduring, as mutually beneficial, as the alliance between Fidel and Gabo. In 1915, when the great Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío (an important influence on García Márquez) was old, ailing, and in need of assistance, he accepted the pandering support of the Guatemalan dictator Manuel Estrada Cabrera and even dedicated some laudatory poems to him. Castro’s political motives for his public association with the great writer are not hard to understand, and as clear as those of Estrada Cabrera: he seeks the dividends of legitimacy. But what motivates García Márquez, who is hardly in the same straits as old Darío?

Now, thanks to this voluminous biography by Gerald Martin, the psychological origins of this extraordinary relationship are beginning to surface. They hark back to the family house in Aracataca, and, in particular, to the bond between Gabito and his personal patriarch, Colonel Márquez. Therein lies the seed of his fascination with power: coded, elusive, but magically real, like the story of the dictionary passed from the Colombian colonel to the Cuban caudillo through the hands of the writer.

"Life is not what one lived but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it," writes García Márquez in the epigraph to his memoirs. This is how he has remembered, re-worked, and in various ways re-told a tragic incident in his grandfather’s life. It took place in 1908, in the city of Barrancas. García Márquez mentions it in Living to Tell the Tale as a "duel," an "affair of honor" in which the colonel had no choice but to confront an old friend and former lieutenant. The man was "a giant sixteen years younger than he was," married and the father of two children, and his name was Medardo Pacheco. The quarrel--in this version—began with "a base remark" about Medardo’s mother that was "attributed" to García Márquez’s grandfather. The "public explanations" for the affront failed to assuage Medardo’s vociferous rage, and the colonel, his "honor wounded," challenged Medardo to a duel to the death. There was "no fixed date," and it took him six months to settle his affairs and assure his family’s future before he went off to meet his fate. "Both men were armed," García Márquez notes. The mortally wounded Medardo collapsed into "the underbrush with a wordless sob."

A previous version of this story, told in an interview with Mario Vargas Llosa, omits the duel: "At some point he had to kill a man, when he was very young … it seems there was someone who kept hounding him and challenging him, but he took no notice until the situation became so difficult that he simply put a bullet in him." According to García Márquez, the town was on his grandfather’s side, so much so that one of the dead man’s brothers slept "at the door to the house, in front of my grandfather’s door, to prevent the family from coming to avenge his death."

"You don’t know how a dead man weighs on you," his grandfather repeated, unburdening himself to Gabito, who listened raptly to his war stories, and who has emphasized the importance of this episode in his life: "It was the first incident from real life that stirred my writer’s instincts and I still have not been able to exorcise it." Precisely in order to exorcise it, he chose to re-create it not as it was lived but as "one remembers it in order to recount it." Perhaps the first literary re-working of the incident came in 1965, in his script for the film Time to Die, by the Mexican filmmaker Arturo Ripstein. After languishing for years in prison, Juan Sáyago returns to the town where he killed another man, Raúl Trueba, after a horse race. Sáyago seeks to rebuild his house and win back the woman he left behind, but the dead man’s sons, convinced that the killing was treacherous, have been waiting for him all this time to have their revenge. The script absolves the protagonist: "Sáyago didn’t kill an unarmed man"; he didn’t kill "dishonorably"; "he killed him face to face, the way men kill." In the end Sáyago has no choice but to kill one of Trueba’s sons, face to face, and then he is shot—in the back, unarmed, dishonorably—by the other.

The same scene recurs in One Hundred Years of Solitude, transformed into a cockfight, after which Aureliano Buendía orders the insolent Prudencio Aguilar to find a weapon so that they may confront each other on equal footing. Only then can he kill Aguilar with a sure thrust of his spear. Like Colonel Márquez in real life, the first Aureliano embarks on an exodus with his family that leads him to found a new town: the real Aracataca, the magical Macondo. But new horizons do not dissipate the shame. Both characters, real and imaginary, live in the grip of "terrible remorse." And both refuse to repent, and repeat: "I’d do it all over again."

After interviewing the descendants of eyewitnesses, Gerald Martin reconstructs a diametrically different version. "There was nothing remotely heroic about it," he concludes. Medardo’s mother was the spurned lover of the boastful colonel; the offended son wanted to cleanse his honor; Márquez (who was forty-four years old at the time) chose "the time, the place, and the manner of the final showdown." He killed Medardo dishonorably: Medardo was unarmed. In Magdalena’s Departmental Gazette for that November, which Martin consulted, the colonel’s imprisonment for "homicide" is mentioned. After a stay in jail, like his literary avatars, he did not return to Barrancas (where he would surely have received the same treatment as Juan Sáyago), but instead set out on the momentous journey to Aracataca, in the hope that the new banana bonanza would bring him prosperity and oblivion.

The bond between grandfather and grandson—researched in detail by Martin—explains the grandson’s need to create that original fiction and to cling to it. "We were always together," remembers García Márquez in his memoirs. They even dressed alike. At home "the only men were my grandfather and me." Separated in early childhood from his parents and surrounded by a herd of "evangelical women"—his grandmother, his aunts, Indian maids—"for me, grandfather was complete security. Only with him did my doubts disappear and did I feel my feet firmly on the ground and myself well established in real life." "Beached in the nostalgia" of that stout and half-blind old man with his black-rimmed spectacles, the grandfather who celebrated his grandson’s "birthday" each month and praised his precocious talent as a story-teller and made him retell the plots of movies when he came home from the theater, García Márquez viewed his grandfather with a worshipful and indulgent sentimentalism, as the incarnation of love and power. "I was eight when he died ... something of me died with him … since then nothing important has happened to me." In Martin’s opinion, this was no exaggeration: "One of the strongest impulses in García Márquez’s later life was the desire to restore himself to his grandfather’s world," which meant inheriting "the old man’s memories, his philosophy of life and political morality," a political morality that fit into a single phrase: "I’d do it all over again."

Gabriel García Márquez’s political consciousness was formed early, by the time he turned twenty, along with his impulse for invention. Here is another one of them. It concerns the literary and autobiographical representation of the United Fruit Company. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, as in Living to Tell the Tale, Aracataca is not just a company town (with its plantations, railroads, telegraph offices, ports, hospitals, and fleets), but also the scene of the "Biblical curse" of Yankee imperialism, a sweeping historical force whose "messianic inspiration" stirred the hopes of thousands (among them García Márquez’s grandparents) only to befoul the waters of the original paradise, disturb its peace, and exploit its people. In its wake, this "plague" left behind only the "leaf-trash," the "scraps of the scraps it had brought us." At the start of his memoirs, recalling his return to the place of his birth with his mother at mid-century, García Márquez portrays his childhood surroundings as a Caribbean apartheid: the "private … forbidden city" of the gringos, with their "slow blue lawns with peacocks and quail, the houses with red roofs and screens on the windows and little round tables with folding chairs for eating, among palm trees and dusty rose bushes. … These were fleeting visions of a remote and unlikely world that was off limits to us mortals."

Are these historical facts, or good stories? Lived reality, or reality re-worked in order to be told? The main driving force behind the company was none other than General Uribe Uribe, who was a former agent of the New York Life Insurance Company, and an economics professor who devoutly believed in the market economy and in agriculture for export. The legendary soldier also owned one of the biggest coffee plantations in Antioquia. Martin makes no mention of these facts, but notes that Uribe Uribe’s comrade Colonel Márquez, the writer’s saintly grandfather, was in fact one of the first beneficiaries of this foreign investment. His nice house in Aracataca may not have had a pool or a tennis court, but it had cement floors, and it was one of the biggest houses in town. Since he was the municipal tax collector, "the Colonel’s own income depended heavily on the financial well-being, physical intoxication and resultant sexual promiscuity of the much despised ‘leaf-trash.’ How conscientiously Nicolás carried out his duties we cannot know but the system was not one which left much freedom for personal probity." The colonel—Martin notes—oversaw establishments called academias, "where both liquor and sex were freely available" and through which must have passed the "unlikely whores" who would serve as inspiration for his grandson’s stories and novels all the way through to his last novel, Memories of My Melancholy Whores.

Swept up by the force of the "remembered" version in One Hundred Years of Solitude, Martin overlooks the family’s ambiguous relationship with the United Fruit Company—a love-hate relationship, typical of Caribbean attitudes toward the Yankees. The company was condemned for its abandonment of the townspeople, but not for its existence. In his memoirs García Márquez notes that his mother, Luisa Santiaga (the real-life version of Úrsula in the famous novel), "yearned for the golden age of the banana company"—that is, for her days as a "rich girl," her clavichord classes, dance classes, English classes. And he himself confessed that he missed his pretty teacher at the Montessori school and his shopping trips with his grandfather.

The truth is that the banana company brought with it much more than leaf-trash. As the anthropologist Catherine C. Legrand explains, the enclave was a melting pot of cosmopolitanism and localism, of "green gold" and witchcraft, of Parker pens, Vicks VapoRub, Quaker Oats, Colgate toothpaste, of Chevrolets and Fords, of magic potions and homeopathic medicine (like that practiced by Eligio, Gabito’s erratic, impecunious, and absent father), of Rosicrucianbooks and Catholic missals, of Masons and theosophists, of demonic tales and modern inventions, of craftsmen and professionals, of residents with centuries-long roots on the coast and immigrants from Italy, Spain, Syria, and Lebanon. García Márquez’s mother would have liked that "false splendor" to last forever. That is why, in the memoirs, when she sees the square where the massacre took place, she says to her son: "That’s where the world ended." Theworld she meant was her world. Paradise did not pre-date the company. Paradise was the world created with the arrival of the company—a tropical alchemy that García Márquez would re-create in his first novels, and, notably, in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

And after the memory of apartheid came that of apocalypse. In 1928, at the request of United Fruit, federal troops opened fire on a gathering of striking workers at the station in Ciénaga, very near Aracataca, where Gabriel García Márquez, who was born the previous year, lived with his grandparents. Hundreds were killed. The slaughter—re-created hyperbolically in One Hundred Years of Solitude—sullied the reputation of the conservative regime and paved the way after 1930 for a series of liberal governments whose important social reforms would encounter opposition from conservatives, who adopted ever more reactionary positions. For the elections of 1946, the dominant liberal party split into two factions, one moderate, in support of Gabriel Turbay, and the other radical, behind charismatic leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán. In his popular anti-imperialist harangues, Gaitán made constant reference to the massacre of 1928, which he had investigated and denounced at the time as a member of parliament. Then, against the backdrop of the ninth Pan-American Conference held in Bogotá on April 9, 1948, Gaitán was assassinated. The episode was known as "El Bogotazo" and was the starting point of a decade of social and political violence known as "La violencia." The young law student Gabriel García Márquez lived the tragedy up close. It was his "political Damascus"—as it was for Castro, who was also in Bogotá at the time. It fueled his hatred of American imperialism and awakened his communist sympathies.

In addition to these two autobiographical and literary re-workings—the glorification of the colonel and the demonization of the banana company—there took shape in the young writer’s political consciousness a mistrust of representative democracy and republican values. Martin seems to share it: "Colombia is a curious country in which the two major parties have ostensibly been bitter enemies for almost two centuries yet have tacitly united to ensure that the people never receive genuine representation." This idea of Colombia as a sham republic is also a re-working that does not correspond to reality. From the earliest decades of the nineteenth century, people in the remotest places in Colombia have been exercised by national politics, taking part in clean and competitive elections, with a real separation of powers, and enjoying—at least in the twentieth century—significant liberties. Except for the fleeting episode of General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla in the 1950s, Colombians have not countenanced coups or dictatorships. It is probably not an exaggeration to say that no other country in the region (not even Chile, Uruguay, Costa Rica, or Venezuela in the second half of the twentieth century, until the arrival of Chávez) has experimented more tenaciously with democracy.

And yet violence seems second nature in Colombia. The main reason for this violence was the discord between liberals and conservatives—a quarrel of political, economic, social, and religious values dating back to the nineteenth century in Latin America. Despite its republican and civil tendencies, Colombia failed to find a formula for stability, and dragged its internecine political and cultural conflict out to the point of exhaustion. In Colombia, the legalist and formal traditions of the reigning grammarians were overturned time and again by the call to arms. "In Colombia," declared President Rafael Nuñez at the end of the nineteenth century, "we have institutionalized anarchy."

This incapacity for peace was manifested once more in the "Bogotazo" of 1948, planting in the young García Márquez an iron sense of the futility of liberal and conservative ideologies. Like Colonel Aureliano Buendía, he came to believe that "the only real difference between liberals and conservatives is that liberals attend the five o’clock mass and conservatives attend the eight o’clock mass." He forever after concurred with Simón Bolívar’s famous statement that "I am convinced to the marrow of my bones that only an able despotism can rule in America." An able despot, a good patriarch, a new and anti-imperialist Uribe Uribe: that would become Gabito’s ideal. To find it, he would embark on a long and difficult path. And instead of cannons, his tools would be words, just as his grandfather wanted.

II.

Gabriel García Márquez: A Life is an authorized biography, the official version of the writer’s literary and political saga. The book is divided into three sections. The first, centered on Colombia from 1899 to 1955, overlaps to a certain degree with Living to Tell the Tale, but it freshens up the family history with new information, and sketches each inhabitant of the extended family in the house of Aracataca, and provides a detailed reconstruction of student life at the prestigious school of San José. It touches on the few joys and the many sorrows of Gárcia Márquez’s family, enriched and impoverished each year by the arrival of a new sibling. And above all, it describes the vicissitudes of a penniless young man in a succession of cities (Cartagena, Barranquilla, Bogotá), surrounded by journalist friends and literary mentors, passionately committed to pursuing a life as a writer, whether by selling encyclopedias or adapting radio soap operas.

Curiously, Martin almost entirely bypasses the cultural context in which García Márquez grew up—the open and happy stamp of the Caribbean, with its extraordinary liberalism, its carnivalesque sensuality, its idolatry of poetry, its musicality, its propensity for outrageous jokes, black magic, and easy death. He somewhat exaggerates the richness and the complexity of García Márquez’s literary education, which seems to have been

limited to Darío and the Spanish Golden Age, quite a bit of Faulkner and Hemingway, some Kafka, almost nothing of the "scandalous" Freud, and even less of the "tortuous" Mann. And Martin almost completely ignores García Márquez’s vast journalistic writing.

Although very few letters or primary documents from private or public archives are cited in his book, Martin—known to the García Márquez clan as "Tío Jeral," as he says in his prologue—spent seventeen years interviewing more than five hundred people: family members, friends, colleagues, editors, biographers, hagiographers, and academics (most of them inclined in the writer’s favor). These testimonies are vivid and sometimes dubious. Some irrefutable firsthand accounts, like that of García Márquez’s all-time friend, the intellectual and diplomat Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, confirm the young writer’s crushing poverty—but did he really live in a room of only ten square feet? Did he really accustom himself to a "virtual disregard of his own bodily needs"? And elsewhere, did he really sleep with the wife of a military man who, upon discovering him in the act, forgave him out of gratitude to his homeopath father? Did he write Leaf Storm, his first novel about Macondo, inspired by the trip with his mother to Aracataca? And did this trip—so strikingly similar, as Martin suggests in a note, to the journey at the start of Pedro Páramo, the novel by Juan Rulfo that was key in setting the tone for One Hundred Years of Solitude—really take place in 1950, and was it as crucial to his work as his memoirs indicate? A letter not mentioned by Martin, dated March 1952 and published in Textos costeños (García Márquez’s first volume of journalism), seems to suggest otherwise:

I’ve just returned from Aracataca. It’s still a dusty village, full of silence and the dead. Unsettling; almost overwhelmingly so, with its old colonels dying in their yards, under the last banana trees, and an impressive number of sixty-year-old virgins, rusty, sweating out the last vestiges of sex at the drowsy hour of two in the afternoon. This time I chanced it, but I don’t think I’ll go back alone, especially after Leaf Storm comes out and the old colonels decide to get out their guns and fight a personal and exclusive civil war against me.

Martin’s second section follows his hero from his European wanderings and his time in Paris in 1955–1957 through his marriage in 1958 to Mercedes Barcha—the shrewd and patient sweetheart of his adolescenc—and his adventures in New York as a reporter for Prensa Latina, the Cuban news agency created after Castro’s triumph, up to the year 1961, when he settled for good in Mexico, a hospitable country (happily authoritarian, anti-imperialist, and orderly, at least at the time). There his two sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo, were born, and there for the first time he made a decent and reliable living at a couple of American advertising agencies (J. Walter Thompson and McCann Erickson) and successfully headed two commercial magazines (La familia and Sucesos para todos). He also tried his luck in the film business and published No One Writes to the Colonel. In Mexico he renewed old friendships (especially with Álvaro Mutis) and started many new ones, no less generous and long-lasting (for example, with Carlos Fuentes), bought his own house and car, enrolled his sons in the American School, was menaced by writer’s block, feared being a victim of a "good situation," and finally, in 1967, at the age of forty, surprised generations of readers with the appearance of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

"Everyone has three lives, a public life, a private life, a secret life," García Márquez warned his biographer. Beyond the notable revelation about the writer’s grandfather, Martin’s book unravels only a single episode in García Márquez’s "secret life": his relationship in Paris—before his marriage, of course—with an aspiring Spanish actress. Stormy and ill-fated, this affair was important not only in itself but as inspiration for No One Writes to the Colonel and the disturbing short story "The Trail of Your Blood in the Snow." But other aspects of his "secret life" remain in shadows. Why did he suddenly break off his relationship with Prensa Latina? Only the Cuban archives, if they are ever opened, can shed light on that. What was the arc of his long epistolary engagement to Mercedes? Impossible to know: both claim to have burned their letters. How did his ties to his fellow writers evolve? Except for the letters exchanged with Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza and a few others, the available literary archives were not consulted by Martin.

The account of the European "private life" of the bohemian writer, who loved to sing and dance, contains touching anecdotes. Is it true that he "collected bottles and old newspapers and one day had to beg in the Metro"? The truth, as Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza points out, is that García Márquez seemed totally uninterested in the experience of Europe. He lived insularly, immersed in his own projects. According to Martin, "it is striking how much of Europe East and West he managed to see," but García Márquez himself corrected Martin: "I just drifted for two years, I just attended to my emotions, my inner world."

Where "public life" is concerned, Martin does cover the journalist García Márquez—in those days a star reporter for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador—as he makes his way through East Germany, Poland, Hungary, and the Soviet Union. He notes, for example, the writer’s strange fascination with Stalin’s embalmed corpse: "nothing impressed me so much as the delicacy of his hands, with their thin transparent nails. They are the hands of a woman." In no way did he resemble "the heartless character whom Nikita Khrushchev denounced in a terrible rant." Martin also records García Márquez’s "intoxication" at the physical proximity of János Kádár, the man who suppressed the Hungarian uprising, whose deeds he strives to justify. Upon learning of the execution of the rebel leader Imre Nagy, García Márquez criticizes the act not in moral terms, but as a "political mistake." "It should perhaps not surprise us," says Martin, in one of his few moments of critical boldness, "that the man who wrote it, who at the time clearly believes that there are ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ men for particular situations and who quite cold-bloodedly puts politics before morality, should eventually support an ‘irreplaceable’ leader like Castro through thick and thin."

The pages dedicated to the writing of One Hundred Years of Solitude are genuinely exciting, but Martin’s conclusion seems excessive. He calls the novel

a work—a mirror—in which his own continent at last recognizes itself, and thus founds a tradition. If it was Borges who designed the viewfinder (like a belated brother Lumière), it is García Márquez who provides the first truly great collective portrait. So Latin Americans would not only recognize themselves but would now be recognized everywhere, universally.

At the time, the enthusiasm with which we all read that extraordinary novel did in fact cause it to be regarded as a kind of Bible (as Fuentes maintained), or at least an "American Amadis" (this was Vargas Llosa’s phrase); but the truth is that García Márquez’s world could not possibly be called the mirror of all Latin America. At least two essential elements were missing from his fictional account: the indigenous dimension and the Catholic faith.

Still, it was an incredible mirror of the Caribbean, which is no small thing. Yet the opinions were not unanimously glowing. Borges commented that "One Hundred Years of Solitude is all right, but it would be better if it was twenty or thirty years shorter." And Octavio Paz’s verdict was also harsh: "García Márquez’s prose is essentially academic, a compromise between journalism and fantasy. Watered-down poetry. He is the continuation of two currents in Latin America: the rural epic and the fantastic novel. He is not untalented, but he is a dilutor." Martin tends to omit these literary critiques, and to dismiss criticism (by Guillermo Cabrera Infante and later by Vargas Llosa himself) of García Márquez’s Castroism, chalking it up to ideological bias and a murky envy of the author of the novel that, according to Martin, "is the axis of Latin America’s twentieth-century literature, the continent’s only undisputable world-historical and world-canonical novel."

The truth is that beginning with the third section of the book, "Celebrity and Politics: 1967–2005," Martin loses his distance. Though he continues to give a lively account of the circumstances in which the subsequent novels were created—the old obsession with power crystallized in The Autumn of the Patriarch, the memory of a real incident witnessed in Sincé by Mercedes in Chronicle of a Death Foretold, his parents’ idyll in Love in the Time of Cholera—Martin does not deviate from García Márquez’s official script. The book begins to read like a vast gossip column. "Private life" bows to "public life": page after page is devoted to an avalanche of dinners, lunches, parties, interviews, declarations, jokes, travels, hotels, restaurants, theaters, birthday parties, Christmas parties, bohemian soirées; a parade of kings, princes, presidents, actresses and actors, artists, writers, members of the avant-garde. Ten Hello!-worthy pages devoted to the Nobel Prize ceremony. Even Gabo’s keenest fans might weary of the passages describing his long march toward the seat of honor that Martin, in his epilogue, calls "Immortality: The New Cervantes." García Márquez claims to have emerged from this labyrinth by putting his fame at the service of a higher and nobler cause. It was the Cuban Revolution.

III.

In the beginning was the representation of power: in the short novels, in One Hundred Years of Solitude (with its old colonels, lonely and despondent, "beyond glory and the nostalgia for glory") and finally, in 1975, in The Autumn of the Patriarch, García Márquez’s own favorite among his books, which, according to the writer himself, was a confession. Martin takes him at his word. The ambitious patriarch, lustful, repugnant, cruel, solitary—above all, solitary—is García Márquez himself, "a very famous writer who is terribly uncomfortable with his fame," and who seeks to unburden himself through an autobiographical book in which the prevailing spirit is a moral striving toward "self-criticism."

The Autumn of the Patriarch was not the first novel about tropical dictators written in Spanish in the twentieth century. There was The Tyrant Banderas (1926), by the Spanish writer Ramón del Valle-Inclán, and Mr. President (1946), by the Guatemalan writer Miguel Ángel Asturias (who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1967). In early 1968, according to the Guatemalan writer Augusto Monterroso, a number of Latin American writers—Monterroso mentions Fuentes, Vargas Llosa, Cortázar, Donoso, Roa Bastos, Alejo Carpentier, but not Gabriel García Márquez—devised a plan to publish books about the dictators of their respective countries. The project was not carried out. "I was afraid I would end up ‘understanding’ and ‘feeling pity’ for him," argued Monterroso, who would have had the grim task of portraying Somoza.

Against this background, it would seem that García Márquez undertook the eventual writing of his dictator novel more in a spirit of competition than contrition. He had spent years turning it over in his head, and he had produced extensive drafts. He would "teach" Asturias and the others "how to write a real dictator novel." And if The Autumn of the Patriarch proved anything, it is that the subject of tyranny makes a good fit with the expressive demands of magical realism.

The abruptness and the arbitrariness of the dictator, his use of power as a form of personal expression, his Dionysian intoxication with his own strength, are natural variations on the magic-real. The patriarch "only knew how to express his most intimate yearnings through the visible symbols of his colossal power." He aspired to be a historical and even cosmic thaumaturge, to alter the forces of nature and the course of time, to twist reality. In a way García Márquez’s patriarch is reminiscent of Camus’s Caligula: "Behold the only free being in all of the Roman empire. Rejoice: at last an emperor has come to teach them freedom.... I live, kill, wield the rapturous power of the destroyer, next to which the power of the creator seems a caricature."

These excesses form part of the reality, and the memory, of many countries. The esteemed Venezuelan writer Alejandro Rossi knew something about this "inherited iconography." Writing in 1975, and not inclined toward magical realism in its most "adolescent and elemental" form, as it manifests itself occasionally in The Autumn of the Patriarch, Rossi praised the "intense and beautifully crafted images," the "intricacies and art" of the prose, and the "often perfect rhythms" of the work—but he objected to its substance:

The incorporation of so many familiar elements turns the book into an elaborate and brilliant exercise that nevertheless does not change our historical and psychological view of dictatorship. The Autumn of the Patriarch aesthetically explores a worn-out and exhausted vision of ourselves. García Márquez’s skill and unquestionable stylistic accomplishments almost never transform the underlying substance, which remains buried in the novel’s cellar, untouched by any literary spark. In that sense it is a Baroque book ... a sealed literary net that sometimes—though with perfect manners—suffocates its narrative subject matter.

The plot of the novel is a record of the tyrant’s subjectivity: his nostalgias, his fears, his sentiments. And the simplicity of his inner world is morally offensive: only rarely does the reader encounter reflections on the obligations and the dilemmas of power, or ruminations on evil, debasement, or cynicism, much less a hint of a crisis of conscience. The top slot in the dictator’s consciousness is reserved for his private woes: the sacrifices that he made for his mother, the chronicle of his lusts and his "unrequited loves." It would almost seem as if the dictator has no public life, only private passions. In this way the historical figure is curiously exempted from history. Conversely, the characters who surround him have no space of their own: everything they think, say, and do is public life, because it revolves around the dictator. In a story in which the central axis is a despot’s lyrical and sentimental I, everything else is reduced to a stage on which that I unfolds. The victims are props.

If García Márquez bears down on the despot, it is not so as to expose or to analyze the inner complexity of a man of state, but to inspire compassion for a sad, solitary old man. The dictator is a victim of the church, the United States, a lack of love, his enemies, his collaborators, his orphanhood, natural disasters, poor health, ancient ignorance, bad luck. After he rapes a woman, she consoles him. There is also the rest house for dictators who have fallen into disgrace, where they spend their afternoons in exile playing dominoes. Their nostalgia assures them immunity. The novel floridly and sentimentally blurs the reality of power, and turns dictatorship into a melodrama. It de-humanizes the victims and re-humanizes the dictator.

In The Autumn of the Patriarch, its prose an overwhelming and uncontainable torrent that sweeps through eras, continents, and characters, the narrative itself becomes autocratic. The book opens with an eighty-seven-page paragraph, an occasionally delicious torment for the reader, that García Márquez justified by saying that "it is a luxury that the author of One Hundred Years of Solitude can permit himself." In this book, there is room only for the consciousness of the dictator. Everything happens through, for, and in the perception of the patriarch. He is the omniscient narrator, the author of a country. Other consciousnesses are secondary, derivative, or non-existent. "Devoted to the messianic pleasure of thinking for us . . . he was the only one who knew the true dimensions of our fate," García Márquez writes. And "in the end, we could no longer imagine what we would be without him." "He alone was the nation"—and the novel.

The book differs in many ways from Mr. President,which is a rather surrealist novel—poetic, political, revolutionary; but perhaps the main difference is that in Asturias’s book one does not hear only the voice of the tyrant. One hears also the voices of "street people." Civilians and military officers speak in anger and in self-criticism, as people with evolving lives of their own. In Asturias’s novel their voices are honored, and experiences of prison and torture are described. When showing abuse, corruption, and the whims of power, the tone is not just unequivocally critical, it is also contemptuous. There is no immunity. In The Autumn of the Patriarch, by contrast, the victims are part of the scenery. They are never active participants in the story.

"The political aspect of the book is a great deal more complex than it seems and I am not prepared to explain it," García Márquez declared when he finished his novel. Martin does feel prepared to decode it: the "solitary writer" (never mind his endless circle of famous friends) had seen his own face in the mirror and "resolved to be better and to do better now that fame had shown him the truth." This moral ascent consisted of putting his fame at the service of a cause—the Cuban Revolution—headed by a man who, paradoxically, would come to bear a certain resemblance to the man in the mirror. "In this absolutely ruthless cynicism about human beings, power and effect," writes Martin, "we find ourselves forced to consider that power is there to be used and that ‘someone has to do this.’" Based on this "Machiavellian" view of history—the adjective, like the logic, is Martin’s—the biographer believes that he understands why García Márquez "would go straight ... to seek a relationship with Fidel Castro, a socialist liberator who was, as it turned out, the Latin American politician with the potential to become the most durable and the most loved of all the continent’s authoritarian figures."

A dictator is an authority figure, I suppose; but a very peculiar one. Perhaps The Autumn of the Patriarch represented the final exorcism of the story of the writer’s grandfather, in which the word "tyrant" softens gently into "patriarch." The patriarch dictates the whole novel, with no periods, commas, or air for anyone to breathe, except for him. It is the novel in which the ghost of Medardo Pacheco, that victim-as-prop complete with spurned mother and ghostly wife and two children, would disappear for all eternity. His voice is silenced, to be heard no more. And after depicting the patriarch in literature, it was time to seek him out in real life. Martin confirms this: it was "Fidel Castro, the only man, his own grandfather figure, against whom he could not, would not dare, would not even wish, to win." From Macondo to Havana: a miracle of magical realism.

Although one of García Márquez’s bits of reporterly advice was to "poison the reader with credibility and rhythm," in his vast body of journalism he did not practice magical realism so much as socialist realism. In Spanish his articles fill no fewer than eight fat volumes, from 1948 to 1991. They have not been translated into English, and Martin barely skims them. This is regrettable, considering that this biography is addressed primarily to an English-speaking audience. The first series of García Márquez’s journalism is important because it gives a glimpse into the secrets of his "basic exercises," his "literary carpentry." The second (1955–1957), which covers his reporting from Europe and America, has more political content, and receives a little more attention from the biographer. But the key political articles, written between 1974 and 1995 and gathered in Por la libre and Notas de prensa—one thousand pages in all—are deemed worthy of only minimal commentary, almost always admiring. And this is disastrous.

Three dispatches that Martin considers "memorable," but does not gloss, were written by García Márquez after a long stay in Cuba in 1975 and titled "Cuba de cabo a rabo," or "Cuba From One End to the Other." They were published in August/September of that year by the magazine Alternativa, founded by García Márquez in Bogotá in 1974. And they were certainly memorable! They professed an absolute faith in the Revolution as it was incarnatedin the heroic figure of the Comandante (whom García Márquez had not yet met): "Every Cuban seems to think that if one day no one else were left in Cuba, he alone, under the leadership of Fidel Castro, could carry on the Revolution, bringing it to its happy conclusion. For me, frankly speaking, this realization was the most exciting and important experience I have ever had. "

Indeed it was, to such a degree that in thirty-four turbulent years García Márquez has never publicly detached himself from that epiphanic vision. What did he see that anyone could see? Tangible achievements in health care and education, though he did not ask himself whether the maintenance of a totalitarian regime was required in order to attain these social objectives. And what didn’t he see? The presence of the Soviet Union, except as a generous purveyor of oil. And what did he say he hadn’t seen? "Individual privileges" (although the Castro family had assumed ownership of the island as its personal estate) and "police repression or discrimination of any kind" (although concentration camps existed, since 1965, for homosexuals, religious believers, and dissidents—they were euphemistically called Military Units to Aid Production, or UMAP).

What he saw, in sum, was what he wanted to see: five million Cubans who belonged to the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, not as the spies and enforcers of the Revolution but as its happy, spontaneous, multitudinous "true force," or, more plainly—in the chilling words of Castro himself, admiringly quoted by García Márquez—"a system of collective revolutionary vigilance that ensures that everybody knows who the man next door is and what he does." He saw many "alimentary and industrial items freely sold in stores" and he prophesied that "in 1980 Cuba will be the first developed country of Latin America." He saw "schools for all," and restaurants "as good as the best in Europe." He saw the "establishment of popular power through universal suffrage by secret ballot from the age of sixteen." He saw a ninety-four-year-old man immersed in his reading "cursing capitalism for all the books he hadn’t read."

Most of all, he saw Fidel. He saw "the almost telepathic system of communication" that he had established with people. "His gaze revealed the hidden softness of his childlike heart … he has survived unscathed the harsh and insidious corrosion of daily power, his secret sorrows. … He has set up a whole system of defense against the cult of personality." Owing to all that, and to his "political intelligence, his instincts and his decency, his almost inhuman capacity for work, his deep identification with and absolute confidence in the wisdom of the masses," Castro had managed to achieve the "coveted and elusive" dream of all rulers: "affection."

These virtues were undergirded, in García Márquez’s account, by Fidel’s "fundamental and most underappreciated skill": his "genius as a reporter." All the great achievements of the Revolution, its origins, its details, its significance, were "chronicled in the speeches of Fidel Castro. Thanks to those great spoken reports, the Cuban people are some of the best informed in the world about their own reality." García Márquez admitted that these speech-pieces "haven’t solved the problems of freedom of expression and revolutionary democracy," and the law that prohibited all creative works opposed to the principles of the Revolution struck him as "alarming"—but not, of course, because of its limitations on freedom. No, what troubled him about the repressive law was its futility: "any writer rash enough to write a book against the Revolution shouldn’t need to stumble over a constitutional stone … the Revolution will be mature enough to digest it." In his view, the Cuban press was still somewhat deficient in information and critical judgment, but one could "foresee" that it would become "democratic, lively, and original," because it would be built on "a new real democracy … popular power conceived as a pyramidal structure that guarantees the base the constant and immediate control of its leaders." (Years later, in an interview with The New York Times, he was asked by Alan Riding why he did not move to Havana, since he traveled there so often. "It would be too difficult to arrive now and adapt to the conditions. I’d miss too many things, I couldn’t live with the lack of information.") "Hell, don’t believe me," García Márquez concluded. "Go see it for yourself."

Another paradigmatic piece of his political journalism—García Márquez’s sterling reputation in the English-speaking world might not survive the translation of his collected journalism into English—is "Vietnam por dentro," or "Vietnam from Inside," which Martin does not mention in his book. A year before it was published, in December 1978, García Márquez had founded an organization called the Habeas Foundation for Human Rights in the Americas, with the aim of "advocating the freeing of prisoners. Rather than taking tyrants to task, it will strive as far as possible to uncover the fate of the disappeared and smooth the way home for exiles. In sum—and unlike other equally vital organizations—Habeas will take a greater immediate interest in helping the oppressed than in condemning the oppressors." In this spirit, it was to be expected that the tragedy of the boat people who fled in desperation from Vietnam would attract his attention, as it attracted that of Sartre and other sympathizers with the Vietnamese regime.

But on his trip to Vietnam the founder of Habeas talked only to one side, and hearkened only to the official story. In García Márquez’s dispatch we are given a magistrate of the Ho Chi Minh People’s Court, a "top official," the Communist Party’s minister of external relations, the mayor of Cholon, the minister of foreign affairs, and, of course, Prime Minister Phan Van Dong, who with "quiet lucidity … received me and my family at an hour when most heads of state are still in bed: at six in the morning." During a stay of "almost a month," García Márquez’s group had occasion to attend "cultural festivities" at which "lovely damsels played the sixteen-string lute and sang doleful airs in memory of the battle dead," but they had no time to listen to the refugees, or to interview them, or to offer them assistance. "Their story," García Márquez wrote candidly, "took second place to the grim reality of the country." This "grim reality," of course, was the history of the war against Yankee imperialism and the danger of a new war with China.

What seemed truly momentous to García Márquez in Vietnam was that it "had lost the war of information." For the founder of Habeas, the calamity was not the hundreds of thousands of fugitives drowned, starving, ill, stripped of their possessions, raped, murdered. The calamity was that the world knew about all this. García Márquez regretted that the Vietnamese—the important Vietnamese, the ones he had interviewed—did not possess the "foresight to calculate the vast scale of the international effort on behalf of the refugees." The humanitarians had outplayed the totalitarians—that is what bothered him.

All these dispatches adhered to the model of García Márquez’s earlier pieces on Hungary, and revealed the pattern of all his political journalism, then and now: to listen only to the voices of the powerful, and to counteract—to withhold, downplay, distort, falsify, and omit—any information that could "play into the hand of imperialism."

IV.

Despite those "memorable dispatches" of 1975, Fidel Castro remarked to Régis Debray that he was not yet convinced of the Colombian writer’s "revolutionary firmness." True, García Márquez had refused to support the Cuban poet Heberto Padilla in the famous affair of his forced "confessions," that tropical echo of the Moscow Trials that led to the break of many Latin American intellectuals with the regime. Castro noted this, but still he wasn’t sure, and so no interview was granted. García Márquez had to content himself at the time with interviewing the strongman of Panama, Omar Torrijos, a second-rank Caribbean dictator but a faithful reader of García Márquez. Torrijos had this to say about The Autumn of the Patriarch: "It’s true, it’s us, what we’re like." "His comment left me astonished and delighted," said García Márquez. And "quite quickly," writes Martin, "the two men would come to build a friendship based on a deep emotional attraction which evidently turned over time into a kind of love affair."

In 1976 García Márquez returned to Cuba, and after waiting for a month (like the legendary colonel) at the Hotel Nacional for a call from the Comandante, the meeting that he had been anticipating for almost two decades finally took place. Once accepted by Castro, and under his personal supervision, he wrote "Operación Carlota: Cuba in Angola," a chronicle that won him an award from the International Press Organization. Mario Vargas Llosa (who had written and published a doctoral thesis on One Hundred Years of Solitude) bluntly called him Castro’s "lackey." Two years later, García Márquez declared that his adherence to the Cuban way was in a sense similar to Catholicism: it was "a Communion with the Saints."

Martin devotes a few passages to describing the growing bond between the Comandante and the writer after 1980. "Ours is an intellectual friendship," García Márquez said in 1982. "When we get together we talk about literature." And it was not just literature that united them. "They began to have an annual vacation together at Castro’s residence at Cayo Largo," Martin records, "where sometimes alone, sometimes with guests, they would sail in his fast launch or his cruiser Acuaramas."

García Márquez’s wife "particularly enjoyed these occasions because Fidel had a special way with women, always attentive and with an old-style gallantry that was both pleasurable and flattering." He also informs us of Castro’s culinary skills, and of Gabo’s taste for caviar and Castro’s for cod. For the Nobel ceremony, Castro sent his friend a boatload of rum, and upon the family’s return he put them up at Protocol House number six, which, just a few years later, would become their Cuban home. There García Márquez "overwhelmed" guests such as Debray with bottles of Veuve Clicquot. "There is no contradiction between being rich and being revolutionary," García Márquez declared, "as long as you are sincere about being a revolutionary and not sincere about being a rich man."

In this vein—not of socialist realism but of socialite realism—Martin could have gotten some juice out of Gabo and Fidel, by Ángel Esteban and Stéphanie Panichelli (which he mentions in his bibliography but does not quote in the book). This volume presents the testimony of the Cuban poet Miguel Barnet, a friend of García Márquez and president of the Fernando Ortiz Foundation. Barnet gives a detailed account of the parties at the "Siboney mansion," describing even the attire of the host. Fidel and Gabo—says Barnet—"are true specialists in culinary matters, and they know how to appreciate good food and good wines. Gabo is the ‘great sybarite,’ because of his love for sweets, cod, seafood, and food in general." And Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, a Spanish writer and friend of Castro, collected the following testimony from the "great Smith," who was perhaps Cuba’s best chef: "Gabo is a great admirer of my cooking and he’s promised me a foreword for my cookbook, which is almost finished." In that cookbook, each of the dishes is dedicated to the person for whom it was created. Gabo’s is "Lobster à la Macondo," and Fidel Castro’s is "Turtle Consommé." It is important to note that in those days the Cuban ration book (which had been introduced in 1962) contained, per month and per person, the following delicacies: seven pounds of rice and thirty ounces of beans, five pounds of sugar, half a pound of oil, four hundred grams of pasta, ten eggs, one pound of frozen chicken, and half a pound of ground meat (chicken), to which fish, mortadella, or sausage could be added as an alternative in the category of "meat products."

In The Autumn of the Patriarch, the Patriarch looks down on the man of letters: "they’ve got fever in their quills like thoroughbred roosters when they are molting so that they are no good for anything except when they are good for something." García Márquez, now with a house of his own on the island, was good for plenty. In December 1986, he established a film academy in San Antonio de los Baños: the New Latin American Cinema Foundation. The new institution—financed by García Márquez—was important for the regime, because culture in Latin America has always been an essential source of legitimacy. Among its guests would be Robert Redford, Steven Spielberg, and Francis Ford Coppola. The academy, as Martin describes it, was a clever and exciting idea: "Cinema was convivial, collective, proactive, youthful; cinema was sexy and cinema was fun. And García Márquez lived every minute of it; he was surrounded by attractive young women and energetic and ambitious but deferential young men, and he was in his element."

Martin is right: García Márquez was "in his element." What Martin does not see is the biographical significance of what he is recounting. The whole thing was like a reconstruction of the Macondian paradise from before the leaf storm, with the advantage that now it was Gabriel García Márquez who lived on the other side, the privileged side, the "American" side. For ordinary Cubans, his Siboney mansion, the lavish meals, the champagne, the seafood, the marvelous pastas prepared by Castro, the yacht outings were—as García Márquez wrote about the "forbidden city" of the Yankees in Aracataca—"fleeting visions of a remote and unlikely world that was veiled to us mortals."

Best of all was once more being able to walk hand in hand with the patriarch. In 1988 García Márquez wrote a profile of the "caudillo" (as he calls him) that was published as the prologue to Habla Fidel, or Fidel Speaks, a book by the Italian Gianni Minà. In this profile he furnished a sweeping literary homage to his hero ("He may be unaware of the force of his presence, which seems to take up all the space in the room, though he isn’t as tall or as big as he seems at first glance"). That same year, living in Havana, García Márquez made progress on a book about Bolívar’s final journey: The General in His Labyrinth. Martin suggests that his description of Bolívar was inspired by traits of Castro, and vice versa.

The following year began badly, with the reverberations of a public letter signed in December 1988 by several writers of international renown who demanded that Castro follow in the footsteps of Pinochet and dare to submit his regime to a plebiscite. For García Márquez—who in the 1970s had expressed his disdain for the institutions, the laws, and the freedoms of "bourgeois" democracy, and in December 1981 had mocked the "crocodile tears" of the "usual anti-Soviets and anti-communists" after the repression of Solidarity in Poland—the letter was another chapter in the rise of the "right" fostered by John Paul II, Thatcher, Reagan, and Gorbachev himself. (In a visit to Moscow in the late 1980s, García Márquez had warned Gorbachev of the danger of surrendering to the empire.)

Of the signatories to this letter of protest against political unfreedom in Cuba, Martin writes that "the American names are not especially impressive, apart from Susan Sontag, nor were the Latin American ones (no Carlos Fuentes, Augusto Roa Bastos, etc.)." Among the American authors who did not impress Martin were Saul Bellow and Elie Wiesel; among the Latin Americans, Reinaldo Arenas (who composed the document), Ernesto Sábato, Mario Vargas Llosa, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and Octavio Paz; among the Europeans, Juan Goytisolo, Federico Fellini, Eugene Ionesco, Czesław Miłosz, and Camilo José Cela.

But this is understandable. For the biographer and for his subject, "1989 would be the year of apocalypse." Even more of a blow to Cuba’s prestige than the downfall of communism in Eastern Europe was the much-talked-about verdict against Division General Arnaldo Ochoa and the brothers Antonio (Tony) and Patricio de la Guardia, on charges of drug trafficking and treason against the Revolution. This dark and ugly episode—to which Martin devotes only a couple of paragraphs—came to public attention in June 1989. According to the journalist Andrés Oppenheimer, the movement of drugs through Cuba began in 1986 and had the tacit blessing of Fidel, until the American intelligence services detected a compromised operation. Castro then took the opportunity to kill four birds with one stone: he could rid himself of a potentially serious enemy (Ochoa was one of the supreme commanders of the intervention in Angola, a veteran of the incursions into Venezuela, Ethiopia, Yemen, and Nicaragua, and officially recognized as a "Hero of the Revolution") along with the de la Guardia brothers, both of them Castro’s friends and attached to the Ministry of the Interior under another "implicated party," the division general José Abrantes. Fidel had entrusted Tony de la Guardia, his "protegé," with multiple intelligence operations (such as the laundering of $60 million for Argentina’s Montoneros in 1975, in payment for a kidnapping). It is hard to believe that this new venture—expressly ordered by Abrantes—did not enjoy Fidel’s blessing, like everything on the island. But the end justified the means.

The remarkable fact is that Antonio de la Guardia, a character out of an action film, was also a close friend of García Márquez. One of his paintings hung in García Márquez’s house in Havana. In that same year, 1989, Gabo dedicated The General in His Labyrinth to him: "For Tony, may he sow good." On July 9, when the final verdict was about to be announced, Castro visited García Márquez at his house in Havana. Oppenheimer reconstructed fragments of the long conversation. "If they are executed," García Márquez is reported to have said, "nobody on earth will believe it wasn’t you who gave the order." Later that night, the writer received Ileana de la Guardia, Tony’s daughter, and her husband Jorge Masseti (the son of the late guerrilla leader Jorge Ricardo Masseti, an old friend and García Márquez’s erstwhile boss at Prensa Latina). They had come to beg García Márquez to intercede on de la Guardia’s behalf, to save his life. The writer said things like "Fidel would be crazy if he allowed the executions," and raised their hopes. He told them not to worry, and advised them not to appeal to any human rights organizations. Four days went by. Then, on July 13, 1989, Gabo’s good friend Tony de la Guardia and Ochoa were executed. Patricio was sentenced to thirty years in prison and Abrantes to twenty. The latter died of a heart attack in 1991.

Although he left Cuba before the execution, according to testimony collected by Ileana de la Guardia herself, García Márquez attended "part of the trial, along with Fidel and Raúl, behind the ‘great mirror’ in the hall of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces." In Paris, during the bicentennial celebration of the French Revolution, he told François Mitterrand that it had all been just "a quarrel among officers." Publicly he claimed to have "very good information" that the charges of "treason" were justified, and he observed that, given the situation, Castro had no alternative.

A few months before the events, writing the final pages of The General in His Labyrinth, García Márquez had depicted Simón Bolívar raving in his sleep as he remembers his order to shoot the brave mulatto general Manuel Piar, who had been invincible against the Spaniards and a hero of the masses. "It was the most savage use of power in his life," García Márquez observes in his novel, "but the most opportune as well, for with it he consolidated his authority, unified his command, and cleared the road to glory." And at the chapter’s climax García Márquez puts his grandfather’s words in Bolívar’s mouth: "I’d do it all over again."

"I don’t publish any book these days," García Márquez said sometime in the mid-1980s, "before the Comandante reads it." Which is why, regarding the passage about Bolívar and Piar, Martin wonders, "Did he [Castro] remember it as he made his decision?" Of course he remembered it. But given the "very good information" that García Márquez has always claimed to have about Cuba, and given his closeness to Antonio de la Guardia, the interesting questions concern not the dictator but the writer. Was García Márquez unaware of his friend Tony’s secret assignments? As he was writing his novel, did he even consider the possibility that his friends would be arrested on charges of purported "treason"?

And so an old cycle of complicity was complete. It began with an execution in the inner circle of the young García Márquez—his grandfather’s shooting of his friend and lieutenant Medardo, his lover’s son—and it ended with another execution in his inner circle: the Comandante’s sentencing of his friend Tony, the sower of good. The writer who, from an early age, adopted his grandfather’s "political morality," the one who "quite cold-bloodedly puts politics before morality," the one who saw Castro as "his own grandfather figure, against whom he could not, would not dare, would not even wish, to win," had been obliged to test his theory in flesh and blood. And he had accepted the verdict of power.

The friendship and the lobsters have continued for twenty years. Panegyrist, court adviser, press agent, ambassador-at-large, plenipotentiary representative, head of foreign public relations: García Márquez has been all these things for Castro. In 1996, he dined with President Clinton and told him that "if you and Fidel could sit face to face, there wouldn’t be any problem left." After September 11, he published a long letter to Bush: "How does it feel now that the horror is erupting in your own yard and not in your neighbor’s living room?"

Things were going pretty well for the writer and the Commandante, except at a few moments, as in 2003, when a movement more important and universal than democracy, the movement for human rights, seemed to come between them. In March of that year, in a sudden and devastating blow, Castro reprised the Moscow Trials, sentencing seventy-eight dissidents to anywhere from twelve to twenty-seven years in prison. (One of them was accused of possessing a Sony tape recorder.) Immediately thereafter, in the heat of the moment, he ordered the execution of three boys who had tried to flee paradise on a ferry. Confronted with this crime, José Saramago declared (though he later retracted his statement) that "this is as far as I go" with his relationship with Castro. But Susan Sontag went further, and at the Bogotá Book Fair, she confronted García Márquez: "He’s this country’s greatest writer and I admire him very much, but it’s unpardonable that he hasn’t spoken out about the latest measures taken by the Cuban regime."

In response, García Márquez seemed to distance himself vaguely from Castro: "Regarding the death penalty, I don’t have anything to add to what I’ve said in private and publicly as long as I can remember: I’m against it in any place, for any reason, in any circumstances." As if the issue were the death penalty! And almost immediately he distanced himself from his distancing: "Some media outlets—among them CNN—are manipulating and distorting my response to Susan Sontag, to make it seem like a statement against the Cuban Revolution." For emphasis, he repeated an old argument, justifying his personal relations with Castro: "I can’t count the number of prisoners, dissidents, and conspirators whom I’ve helped, in absolute silence, to get out of jail or emigrate from Cuba over the last twenty years at least."

In "absolute silence" or in absolute complicity? Why would García Márquez have helped anyone leave Cuba if he did not consider their imprisonment unjust? And if he considered it unjust, to the extent of championing their cause, why did he continue—why does he still continue—to support a regime that commits such injustices? Wouldn’t it have been more valuable to denounce the unjust incarceration of those "prisoners, dissidents, and conspirators" and thus help to abolish the political prison system?

Gabriel García Márquez is not a hothouse writer. He claims to be proud of his work as a reporter. He promotes journalism at an academy in Colombia. He has asserted that the news story is a literary genre with the potential to be "not just true to life but better than life. It’s as good as a story or a novel, but with one sacred and inviolable difference: novels and stories permit unlimited fabrication but news stories have to be true down to the last comma." How, then, to reconcile this declaration of journalistic ethics with his own concealment of the truth in Cuba, despite his possession of privileged inside information?

Eventually history makes both aesthetic and moral judgments. Aesthetically speaking, it is a little premature to say that García Márquez is the "new Cervantes." But in moral terms, certainly, there is no comparison. A hero in the war against the Turks, wounded and maimed in battle, castaway and prisoner in Algeria for five years, Cervantes lived his ideals, his tribulations, and his poverty with Quixote-like integrity, and enjoyed the supreme freedom of accepting his defeats with humor. There is not a trace of such greatness of spirit in García Márquez, who has avidly collaborated with oppression and dictatorship. Cervantes? Not by a long shot.

The beauties of the fiction of Gabriel García Márquez will survive the twisted loyalties of the man who created it, just as the work of Céline survives his passion for the Nazis and the work of Pound survives his admiration for Mussolini. But it would be an act of poetic justice if, in the autumn of his life and at the zenith of his glory, he disassociated himself from Fidel Castro and put his influence at the service of the Cuban boat people. There is no point in hoping for such a transformation, of course. It is the kind of thing that happens only in García Márquez novels.

Enrique Krauze is the editor of Letras Libres. This essay was translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer.