They brought Che Guevara at five o'clock in the afternoon of October 9 to the airfield outside the small town of Vallegrande in southeastern Bolivia. The fighting had been fierce. Che had been among the first casualties and his comrades had been fighting viciously to recover the body. They failed. Most of them also fell, among them Che's Cuban bodyguards Antonio and Pancho. The remainder, after 30 hours of battle, managed to get away, pursued by the Bolivian army's tough, US-trained Rangers.

Che's body was brought in tied to the landing shafts of a helicopter, swirling gently down at the airport one hour before dusk. A car was waiting at the far end of the field; so were, it seemed, most of Vallegrande's 10,000 inhabitants. Soldiers tried to keep the crowds away, but as the helicopter touched down, they lost control. Even the soldiers ran toward the helicopter, and behind them came the crowds. When eventually they came to their senses, the soldiers turned about and pointed menacingly at the civilians, forcing them to stay where they were. From the air it must have looked like a gigantic chess game, with pawns frozen in absurd positions. Meanwhile, the helicopter unloaded the body into the automobile, and the car rapidly took off toward the hospital of Vallegrande.

That is where, a few minutes later, I got my first glimpse of Guevara. They had taken him to an outdoor morgue that looked rather more like a stable on a small hill above the hospital. About 10 persons--doctors, soldiers, nurses--were around the body, working frantically. A nun dressed in white was standing at the body's head. Now and then she smiled gently.

At flrst, I thought Che was still alive. It looked as if the doctors were administering a blood transfusion. Through two openings in the neck, they were injecting liquid from a vessel being held by a soldier standing with his legs wide apart above the body. Then I was told they were filling the body with formalin to embalm it.

It was a ghastly sight. Not so much because of the corpse, whose face as the soldiers lifted its head seemed rather peaceful. But there was the white-clad nun, smiling encouragingly; and the laughing soldiers who were slapping each others' backs; and a sturdy man in battle dress and an American T-shirt, with a very modern machine-gun, who seemed somehow to be in charge of the whole performance. He saw to it that the fingerprints were properly taken. He waved at the soldiers not to disturb the doctors and nurses at work, and above all he seemed bent on keeping journalists away. Earlier in the day he had ejected two British journalists from Vallegrande's airfield, as they were taking pictures of the troops. He was overheard saying, "Let's get the hell out of here," in a most American way. But at this point he was taciturn, answered questions only in Spanish, and shied away from having his photograph taken. His name is Ramos, one of the Bolivian journalists told me. He is a Cuban refugee, employed, the journalist said, by the Central Intelligence Agency. The Americans brought him and a half-dozen other Cubans here to interrogate guerrilla prisoners.

This, then, was to be Che Guevara's fate: a slab of meat tied to a helicopter, carried from the battlefield in the jungle to a morgue in Vallegrande, laid out in front of the press, and-- to top it all--identified and inspected by a refugee gusano from Cuba, whose pleasure and satisfaction it was to check personally that his most hated enemy, next to Fidel Castro, was dead.

As long as they were busy filling the body with formalin, it was rather difficult to see who it really was. The head was thrown back, the long hair was dangling and almost touching the floor. The stench of the formalin was almost impossible to stomach. Suddenly, one of the soldiers grabbed the body by its hair and yanked it into a sitting position.

There was no doubt about it. It was Che, much slimmer than he used to be in the old photographs, smiling at Punta del Este, cutting cane in Cuba. But that seemed to be a normal consequence of half a year in the Bolivian jungle. He didn't look emaciated, as one had been given to believe by Bolivian army reports that Che, known as "Ramon" among the Bolivian guerrillas, was a very sick man, suffering from asthma and rheumatism, and finding it impossible to walk.

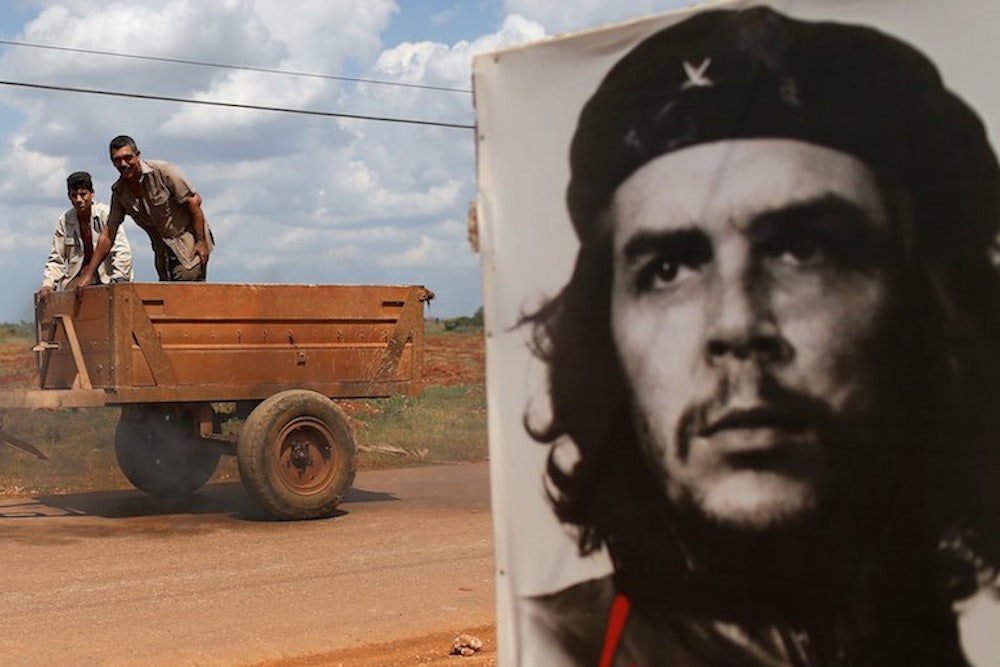

I recalled a picture that had been hanging in every newsstand in La Paz during the last month. It was originally from Paris-Match and showed Che delightfully stretched out on a sofa, like some kind of male model for a female edition of Playboy. That picture was supposedly taken shortly before his disappearance from Cuba in 1965. Crowds had stood around that picture in La Paz, reading eagerly every word about the mysterious Number One Revolutionary of Latin America. And now here, in the improvised morgue which had been set up at Vallegrande, the picture had its dreadful counterpart.

They were washing the body. "Show some respect," a Bolivian army sergeant exhorted the journalists, "at least don't take pictures of him in the nude." A captain threateningly showed a film he had grabbed from a bystander's camera and confiscated. The soldiers were trying to dress the body. They got the trousers on, but when they tried to put on the jacket, it turned out that the arms were already getting stiff. And so they had to give up their attempt.

General Ovando, chief of the Bolivian armed forces, was inspecting the ceremony in person. One of the radio reporters, representing a station in Santa Cruz, talked into his tape recorder: "This is Vallegrande. The leader of the Castro communist invasion of our fatherland has fallen here, thanks to the effort of the Bolivian armed forces, commanded by the glorious General Ovando." The general smiled a delphic smile.

How had Che died? He had been captured Sunday night, the army said; he was mortally wounded and had died early Monday morning. Impossible, the doctors said. Che died from wounds in the heart and both lungs, around noon Monday, five or six hours before he was brought to Vallegrande. What conclusion must one draw?--that Che had been coolly executed after his capture.

If the army officials had stuck to one story from the beginning, they would have fared better. But while Colonel Zenteno, chief of the Eighth Division in Santa Cruz, who was directly responsible for the killing of Che, maintained Che had died immediately, officials higher up talked freely of what Che had said and how he had acted after his capture. I flew to Vallegrande in a military transport plane from Santa Cruz, together with Admiral Ugarteche, commander-in-chief of the Bolivian navy, who said: "I have been told that Che's last words were: 'I am Che. Don't kill me. I have failed.' I have the impression he wanted to save his life. It's very often like that. In battle, you don't feel fear, but afterwards you become a coward."

The crowd outside the hospital had broken through the gates and were now streaming upwards toward the morgue. The soldiers kept them at a distance, but when finally the body was brought out on a stretcher for the benefit of the journalists, men, women, little girls came forward and the soldiers carrying the stretcher dropped it. For a short while, I thought the crowd was going to tear the body apart. Then the soldiers once again gained control and the body was brought back to the morgue. That's where I threw a last glance at it. "The forehead," I thought, "those very heavy, almost swollen lobes above the eyebrows, that ought to be one of the surest ways to identify Che."

I looked at the body. The lobes were very heavy, strongly accentuated. If this was not Che, it was his twin brother.

We went by jeep back to Santa Cruz, and then on to La Paz to tell the world Che was gone.

He had left Cuba in March 1965 because there was no longer a place for him in the Cuban political leadership and because the Russians on whom the Cubans depend in order to survive the American embargo, wanted Guevara out of the way. He was their enemy. On his last official journey around the world, in the spring of 1965, Che had caused a sensation in Algiers when he made a scathing attack on the Russians. Then Guevara returned home and disappeared. It did not seem far-fetched to assume he had been liquidated.

Only now is it possible to piece together Che's itinerary after his disappearance. He seems to have traveled widely in Latin America, appearing now and then in Guatemala, where guerrillas are active, in Peru and in Brazil. He used various passports, some of which the Bolivian government found in a dead guerrilla fighter's mochila. He may have been in the Congo. He most certainly at one time or another was in North Vietnam, where the hard-core Bolivian guerrillas were sent for training as a kind of revolutionary counterpart to the American Special Forces who get their training in South Vietnam and use their knowledge to train highly efficient Bolivian Rangers. For a couple of weeks during the spring of 1966, Guevara was in Paris; then in late 1966, he arrived in Bolivia.

His affection for Bolivia apparently began when, as a young student in the fifties, he had bummed his way around Latin America. Bolivia had had a glorious revolution; its army had been completely wiped out in three days of heavy battle in April 1952; the tin mines had been nationalized, the large estates broken up. But the army was recreated by President Victor Paz Estenssoro; life for the miners was still bad; land reform did nothing to improve agriculture; the peasants' trade unions soon turned into armed gangs used by sindicato leaders for their own ends.

It was easy for Che Guevara to conclude later that the Bolivian revolution had failed because it hadn't gone whole hog as had the Cuban's. But he apparently had no illusions that the Bolivians could repeat, the Cuban pattern. For one thing, the Cuban revolution had taken place at a time when the Soviet Union was favorably inclined to helping revolutions in the Third World. This was no longer so, Che had observed; then too, the Cuban revolution was at the outset at least tolerated by the United States. But not even democratic liberal, "constitutional" revolutions, such as the one in the Dominican Republic in 1965, would any longer be tolerated by the US, he thought. A successful revolution in Bolivia would mean intervention on a massive scale by US troops, Che believed, and this actually was what he was aiming for. In his 1967 message to the Tricontinental Conference in Havana, written when he already was in Bolivia, he exhorted revolutionaries all over Latin America to create "two, three, many Vietnams" and try to bleed the American military forces to death. As he was writing that message, he himself was actively training his men in Kfancahuazu in southern Bolivia to do just that.

It is now known that Guevara appeared at a secret meeting in Prague in early May 1965, after his disappearance from Cuba. At the meeting, a group of Bolivians, who were later to become the nucleus of the guerrilla force, listened to Che explain that they had to prepare themselves by studying the revolutionary situation in Latin America, but above all by preparing themselves militarily. One of those attending was Coco Peredo, member of the Bolivian Communist Party's Central Committee, and by profession a taxi driver in La Paz, who immediately proceeded to North Vietnam, where for the next year he and others were given training in guerrilla warfare. In late 1966, they resurfaced in Bolivia, where a farm had been bought, and where military training was taking place, much as Fidel and Che 10 years earlier had trained their troops on a deserted farm in the state of Michoacan in Mexico. But things didn't go as planned. In early 1967, both the CIA and the Bolivian army were aware something was going on. A member of the original nucleus had talked, and, it is believed, had done so for money. In March, after a sudden battle with Bolivian troops in the area, the guerrillas had to move on hurriedly.

They did fairly well up till August. Then the Rangers encircled the main body of them. Joaquin, one of the Cuban advisers, and Tania, an Argentinian girl who served as liaison officer, and several others were killed at a river pass in August. In late September, Coco Peredo was killed. Less than two weeks later, Guevara.