In 2009, Ralph Nader published a fantasia titled Only the Super-Rich Can Save Us!, in which he imagined a group of maverick billionaires banding together to defeat corporate power in America. Declaring themselves “the Meliorists,” these enlightened oligarchs force Walmart to unionize, elect Warren Beatty governor of California, establish single-payer health insurance, raise the minimum wage to a livable salary, and in general breathe life back into liberalism.

In 2012, something like Nader’s utopian scenario has begun to take shape, but with a radically different ideology. Super-rich, hard-right tycoons like Foster Friess (mutual funds), Harold Simmons (chemicals and metals), Bob Perry (home-building), and Sheldon Adelson (casinos) are, through the new vehicle called the super PAC, leveraging their fortunes to seize hold of the political process. Super PACs have made it so easy for millionaires and billionaires to spend unlimited sums on behalf of a particular candidate that these groups are now routinely outspending Republican presidential primary campaigns. Indeed, to a remarkable extent, these oligarch-controlled super PACs are the primary campaign. And, while both parties can create super PACs, so far GOP super PACs are burying their Democratic counterparts. Of the top ten individuals funding super PACs, only one—Jeffrey Katzenberg—is a Democrat.

The very rich funders of Republican super PACs, while hardly unanimous in their views (they support opposing candidates, after all), are reliably anti-Meliorist. Their favored causes tend toward things like repealing health care reform, making abortion illegal, restricting access to contraception, blocking climate change legislation, cutting taxes for the 1 percent, and in general halting America’s moral decay—excepting greed or gambling—and its steady march toward socialism. (Simmons and Adelson have both used the “s” word to describe either President Obama or his policies.)

It’s enough to make you nostalgic for an America in thrall to corporate power. Corporations, after all—the publicly held ones, anyway—must answer to their stockholders. Super-rich crankocrats do not. (Neither do the billionaire altruists in Only The Super-Rich Can Save Us!, but Nader avoids the issue by assuming his semi-fictional billionaires to be wholly benign.)

A corporate takeover of U.S. politics was precisely what many predicted after the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United. But, although the Roberts court recklessly invited corporations to make so-called “independent expenditures” on behalf of individual candidates, most corporations have been reluctant to do so. The Washington Post reports that less than one-quarter of the money given to super PACs in this election cycle came from corporations, and most of these were private. According to Politico, less than 0.5 percent given to “the most active Super PACs” came from publicly traded corporations.

Instead, it’s rich crackpots who opened the floodgates after a lower-court ruling loosened the rules a bit further. Journalist Brooks Jackson, author of Honest Graft: Big Money and the American Political Process, suggests crankocrats may also have been guided inadvertently to super PACs by the 2002 McCain-Feingold campaign finance law’s ban on unlimited “soft-money” contributions to national political parties, which survived Citizens United. “A lot of these cranks previously funneled their money through the RNC and DNC, ... which at least had the sense to know that they needed to win majorities,” Jackson e-mailed me. “Now the crank money flows through independent groups instead.” Applying some Occupy-Wall-Street-style math, CNN’s Charles Riley calculates that for 2011–2012 the 100 biggest individual donors to super PACs make up only 3.7 percent of the contributors but supply more than 80 percent of the cash. If you give to a super PAC and don’t own a private jet, paint yourself a sign that reads, “WE ARE THE 96.3 PERCENT!”

Why did corporations mostly shun electioneering? Because openly supporting the election of one person over another (as opposed to the quieter and more predictable business of lobbying) is just the sort of risky activity that corporations like to avoid. In 2010, Target had to apologize after a $150,000 corporate contribution to a pro-business political group prompted protests and a boycott because the group’s favored Minnesota gubernatorial candidate turned out to be anti-gay. After Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) late last year gave $10,000 to a super PAC supporting Democratic representative Howard Berman of California, Berman’s opponent sent out a mailer accusing PG&E of skimping on pipeline maintenance. Not a lot of public corporations have much stomach for this type of conflict.

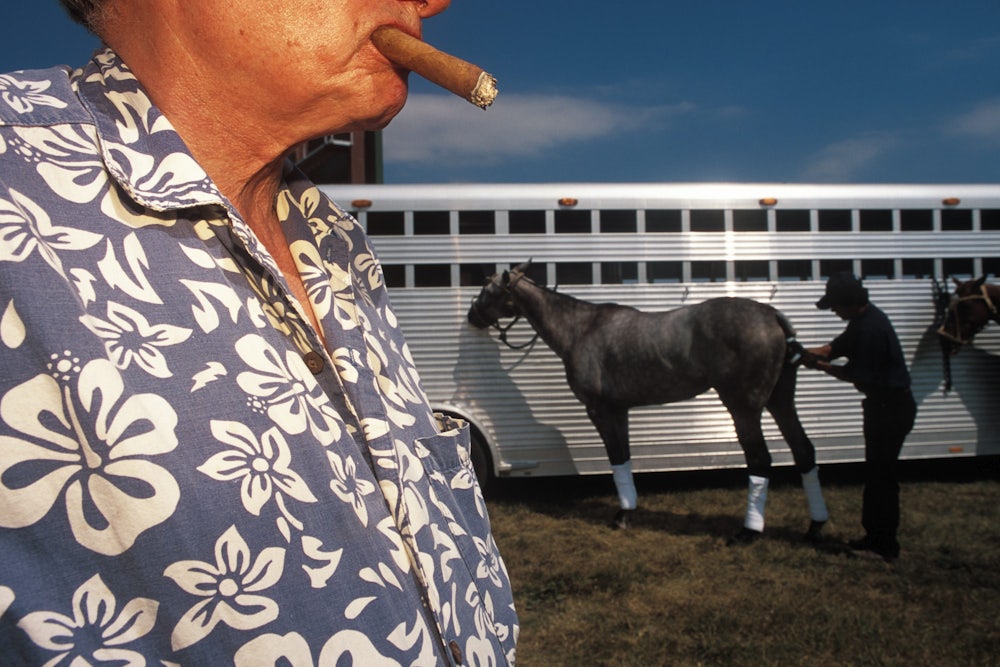

Unlike Nader’s Meliorists, the crankocrats usually keep a low public profile. When they do speak to the press, they’re at serious risk of creating grief for their candidates. Friess lit up the phones at MSNBC when, asked whether health insurance should be required to cover contraception, he joked: “Back in my day, they used Bayer Aspirin for contraceptives. The gals put it between their knees, and it wasn’t that costly.” Simmons recently told The Wall Street Journal, with some regret, “We could have killed Obama” in 2004. Memo to the Secret Service: Simmons meant the candidacy, not the candidate.

To be sure, rich people hadn’t exactly stopped giving large sums to influence politics after post-Watergate election reforms were passed in 1974. They contributed soft money to political parties. After the Supreme Court struck down parts of the 1974 law, they made independent expenditures that followed relatively strict rules about not coordinating with the candidates or political parties. After McCain-Feingold banned soft money, they gave to 527s, which could not advocate openly for a particular candidate. In 2004, the leading 527s bent the rules too far and ended up paying fines. They also gave to 501(c)(4)s, which could promote candidates but only secondarily to promoting “social welfare.” But super PACs eliminated all restrictions on electioneering and, practically speaking, nearly all restrictions on coordinating with campaigns.

Just about the only thing super PACs can’t easily do is organize supporters at the grassroots, because that usually can’t be done without extremely close coordination with the campaign. But the crankocrats likely wouldn’t have patience for that anyway. It’s too social, and you can’t be much of a crank if you have to listen to other people.

Timothy Noah is a senior editor at The New Republic. This article appeared in the April 19, 2012 issue of the magazine.