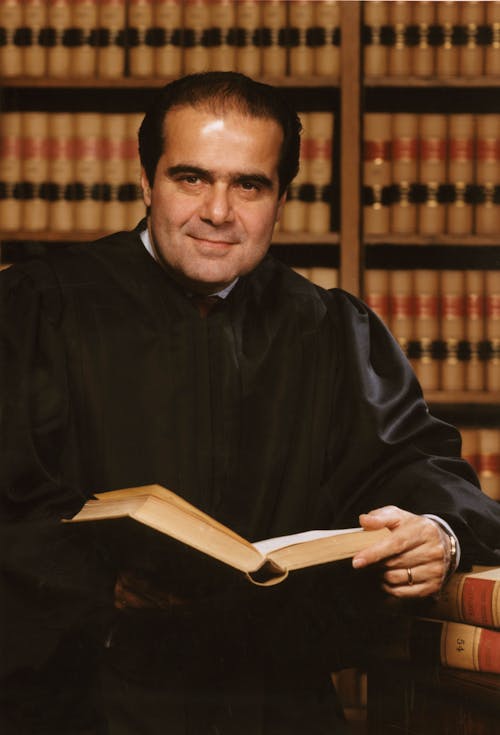

Legal decisions are very rarely read for pleasure. All too many judges feel that the majesty of the law needs to be protected with the barbed wire of rebarbative prose, prickly with forbidding jargon and headache-inducing abstraction. There have always been exceptions to this rule, judges who craft their words with brio, force, and wit, whose obiter dicta are rife with vernacular charm. This is the tradition of Supreme Court justices Benjamin Cardozo, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Robert Jackson. The one current justice who has the strongest claim to belong in this elite pantheon is Antonin Scalia.

As he proved once again in his peppery dissent in King v. Burwell, Scalia is the foremost living practitioner of performative legal prose, a masterful writer who can make torts tarty and judgments jazzy. Scalia’s dissent is full of the little touches that make his writing so delightful, such as the piquant slang (notably “jiggery-pokery” and “pure applesauce,” wonderfully quaint euphemisms for “bullshit”). Scalia’s dissent also gave voice to his familiar wrathful disdain for the pettifogging prose of his inferiors, as when he snorted, "Lawmakers sometimes repeat themselves—whether out of a desire to add emphasis, a sense of belt-and-suspenders caution, or a lawyerly penchant for doublets (aid and abet, cease and desist, null and void)."

Scalia’s reactionary jurisprudence has made him a polarizing figure, but the pungency of his writing is widely admired even by those who fear that he will return America to the dark ages. Writing in the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy in 1993, Harvard law professor Charles Fried hailed Scalia as possessing “a natural talent” of “the kind which distinguishes a Mozart from a Salieri.” In the Journal of the Legal Writing Institute in 2003, Yury Kapgan claimed that Scalia’s decisions are “as close to literature as court opinions come.”

What are the hallmarks of Scalia’s prose that make him so singular a writer? Style, in Scalia, is as much about attitude as word choice. A haughty conservative who feels that Americans have abandoned the truths of the Founding Father, Scalia uses his decisions to give vent to invective that is completely injudicious. His eagerness to score points against his fellow judges might be politically dunderheaded since it has alienated potential allies in the court but it energizes his prose with rage. As Kapgan notes, Scalia’s dissents are often “vitriolic.” Sarcasm, Kapgan rightly observes, “is indeed par for Scalia’s course.” Another legal scholar, Patricia Wald, writing in the University of Chicago Law Review, notes that Scalia “uses conceptual phrases sarcastically, always set out in capital letters.” This sneering tone makes Scalia’s dissents hugely entertaining even where they are not rhetorically persuasive

Consider his infamous dissent on Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), where Scalia implies that unwillingness of his colleagues to overturn Roe v. Wade is setting America on the path towards Nazism.

The Imperial Judiciary lives. It is instructive to compare this Nietzschean vision of unelected, life-tenured judges — leading a Volk who will be 'tested by following' and whose 'very belief in themselves' is mystically bound up in their 'understanding' of a Court that 'speak[s] before all others for their constitutional ideals' — with the somewhat more modest role envisioned for these lawyers by the Founders.

Scalia has amazing tonal range. If the passage above is pure spleen, another section of Casey, where Scalia compares his fellow judges to the notorious Justice Roger Taney who tried to make slavery a permanent institution in Dred Scott, is as somber as a gothic novel.

There comes vividly to mind a portrait by Emanuel Leutze that hangs in the Harvard Law School: Roger Brooke Taney, painted in 1859, the 82d year of his life, the 24th of his Chief Justiceship, the second after his opinion in Dred Scott. He is all in black, sitting in a shadowed red armchair, left hand resting upon a pad of paper in his lap, right hand hanging limply, almost lifelessly, beside the inner arm of the chair. He sits facing the viewer, and staring straight out. There seems to be on his face, and in his deep-set eyes, an expression of profound sadness and disillusionment. Perhaps he always looked that way, even when dwelling upon the happiest of thoughts. But those of us who know how the lustre of his great Chief Justiceship came to be eclipsed by Dred Scott cannot help believing that he had that case—its already apparent consequences for the Court, and its soon-to-be-played-out consequences for the Nation—burning on his mind. I expect that two years earlier he, too, had thought himself “call[ing] the contending sides of national controversy to end their national division by accepting a common mandate rooted in the Constitution.”

As always with Scalia, it’s worth making a distinction between the substance and the style. On the merits, comparing his colleagues to the judge who presided over Dred Scott is pure mudslinging. But Scalia wins us over to his words, if not his ideas, with his evocative and convincing portraiture of Taney, which calls to mind one of Edgar Allan Poe’s moldering, haunted protagonists.

Scalia's unbridled and undisguised contempt for his colleagues shines forth even more strongly in his dissent in today's marriage equality case, Obergefell v. Hodges, where in a footnote he wrote:

If, even as the price to be paid for a fifth vote, I ever joined an opinion for the Court that began: "The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that all persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity," I would hide my head in a bag. The Supreme Court of the United States has descended from the disciplined reasoning of John Marshall and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.

Connoisseurs of Scalian word-magic often dwell on his virtuoso’s skill at playing an extended metaphors. Fried extolled Scalia’s “sustained, almost Homeric use of metaphor.” As Yury Kapgan notes one of “the most humorous” passages in the Scalia oeuvre is the extended metaphor he contrived in his concurrence for the 1993 decision Lamb’s Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free School District.

As to the Court’s invocation of the Lemon test: like some ghoul in a late-night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad after being repeatedly killed and buried, Lemon stalks our Establishment Clause jurisprudence once again, frightening the little children and school attorneys of Center Moriches Union Free School District. Its most recent burial, only last Term, was, to be sure, not fully six-feet under: our decision in Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. ___ (1992), conspicuously avoided using the supposed “test,” but also declined the invitation to repudiate it. Over the years, however, no fewer than five of the currently sitting Justices have, in their own opinions, personally driven pencils through the creature’s heart (the author of today’s opinion repeatedly), and a sixth has joined an opinion doing so….

The secret of the Lemon test’s survival, I think, is that it is so easy to kill. It is there to scare us (and our audience) when we wish it to do so, but we can command it to return to the tomb at will…. Such a docile and useful monster is worth keeping around, at least in a somnolent state; one never knows when one might need him.

It is possible that Scalia’s hard-right politics are linked to his literary gifts. The commanding literary critic Lionel Trilling noted in his 1965 book Beyond Culture that many of the “monumental figures of our time” have treated “liberal ideology” as “at best a matter of indifference.” Trilling cited writers like Marcel Proust, D.H. Lawrence, and W.B. Yeats. He could have added T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, Ford Madox Ford, and Evelyn Waugh. All of these writers possessed the reactionary imagination. Their art was animated by some vision of a paradise lost, an organic unity in the past that was being irrevocably destroyed. To some extent, Scalia deserves to be classed with the great Tory modernists. Like them, his puissant language is powered by a terrible sense of longing, a palpable feeling for the world we have lost. It’s precisely those qualities that make Scalia so politically reprehensible that also make him a great legal writer.