“Another day, another corpse,” a radio DJ gleefully announces in the opening minutes of Wicked City, which premiered Tuesday night on ABC. According to the DJ’s voiceover, Los Angeles is the “murder capital of the country,” but watching Wicked City, you have to wonder if the real murder capital is primetime TV, and, by extension, our living rooms. We soar over the Hollywood sign and straight into a fresh crime scene, where Detective Jack Roth (an impressively gristly Jeremy Sisto) steps out of his sedan and prepares to deliver a performance anyone who has ever watched a police procedural could easily write themselves. First the required lines: “Looks like he’s done this before”; “To me, this girl is a victim”; “You’re off the case!” Then the wordless, chagrined sigh, and the pained glance down at the series’ inaugural dead girl. Open season has begun.

Wicked City takes place in the summer of 1982, when America’s actual murder capital was Odessa, Texas (beating out Miami by a narrow margin), but the show’s creators won’t let that ruin our fun. For most of its premiere, Wicked City seems like it was also made in 1982; Detective Roth’s investigative techniques may not be strictly by the book, but his character is. The reluctance to work with a partner, the mysterious and traumatic past, the dirty little secrets, and the determination to get the job done (he just cares too much!) all arrive as predictably and as satisfyingly as the ‘80s hits dutifully crammed into the show’s soundtrack. Wicked City isn’t above satisfying our desire for the obvious. Do we want to hear Foreigner’s “Feels Like the First Time” as gruesome theme music for our murderer’s maiden voyage? Yes, of course we do. Do we want to see Detective Roth glance warily at a TV crew’s camera, push himself too hard on his morning jog, and bark “Don’t give me your Constitution crap!” at a photographer? Yes, of course we do. And it’s hard to fault Jeremy Sisto or Gabriel Luna (who plays Paco Contreras, Roth’s ripped-from-the-screenplay-of-Dirty-Harry partner) for not doing much to give this material an original spin. For one thing, that might be an impossible task. For another, Sisto and Luna probably know that their performances are supposed to be comfortingly predictable enough to allow the show’s other plot a little leeway for transgression—to be the dry white bun holding the whole bloody mess together.

As bloody messes go, Wicked City is still fairly tidy, but it shows promise in the form of its burgeoning serial killer, Kent (Ed Westwick of Gossip Girl), and his new squeeze Betty (Erika Christensen of Parenthood). ABC’s promos have already promised us that Kent and Betty will be a “killer couple,” and that, in 1982, “their passion brought fear to the Sunset Strip.” The premiere of Wicked City only shows us the start of Kent and Betty’s relationship, and though we are exposed to Kent’s murderous activities (and musical tastes) before we even see the opening credits, Betty remains more of a mystery. All we know is she has a faint, secret taste for inflicting pain, and that the danger Kent has exposed her to so far has given her a hunger for more.

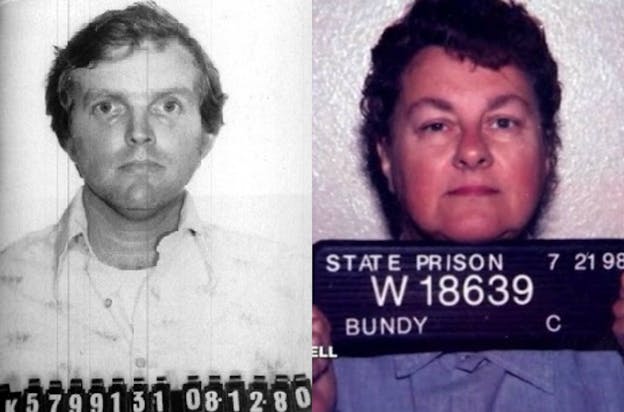

While Wicked City jams its fictional killers into the true crime canon by name-checking the Hillside Stranglers—Angelo Buono and Kenneth Bianchi—within its first few minutes, the fictional Kent and Betty owe more to another real-life dyad: Carol Bundy (no relation to Ted) and Doug Clark. Thanks to euphemism-happy headline writers, Bundy and Clark became known in the summer of 1980 as the Sunset Strip Killers and the Hollywood Slashers, murdering and dismembering a string of teenage runaways and prostitutes. After their arrest in August, each predictably blamed the other. Doug Clark ended up on death row (where he remains), while Carol Bundy’s primary crime, in the eyes of both the media and the court, was complicity. She had helped Clark to indulge in his necrophiliac fantasies, but within two months confessed her actions to an ex-lover—though if she was motivated by a guilty conscience, it didn’t last long, since she immediately murdered and beheaded him. Days later, however, she confessed this murder to her coworkers, and both Sunset Strip Killers were quickly apprehended. Carol Bundy died in prison in 2003, and her motives for collaborating with Doug Clark still remain unclear. Do her later confessions suggest a degree of conscience? Was she in Clark’s thrall, or did she play just as active of a role as he did? Would either one have embarked on a crime spree if they hadn’t met the other? Did she enjoy killing? And is it possible—is it ever possible—to blame the carnage they left in their wake on love?

In the popular version of the couples-who-kill story, love always accepts the brunt of the blame: think of Natural Born Killers’ Mickey and Mallory Knox, True Romance’s Clarence and Alabama Worley, and, of course, Bonnie and Clyde’s Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. Applying this logic to serial murder is a little trickier. Those cinematic couples may have cut wide swaths of chaos across America, but largely because the world—in the form of abusive parents, maniac cops, and killer pimps—was already against them. Their crimes are bloody, but they aren’t premeditated. Viewers watch these movies and see not killing for killing’s sake but the kamikaze flare of pure love in an impure world. It’s a dangerous narrative, but not one that lionizes sociopathic tendencies. Trying to tell the story of two people who love each other less than they love the act of killing, as Wicked City seems to be trying to do, brings an entirely different set of challenges. There is a reason Bundy and Clark’s crime spree has never been immortalized onscreen.

Wicked City may have taken inspiration from the middle-aged Douglas Clark and Carol Bundy, but, as appearances go, its youthful and well-manicured killers bear a far greater resemblance to Canadian couple Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka. Bernardo and Homolka met in October 1987, when Bernardo, a 23-year-old junior accountant, was already active as a violent serial rapist. Karla Homolka, a 17-year-old high school student, had never displayed any violent tendencies, and for a year afterwards the only notable feature of her life was how much she seemed to worship Paul Bernardo, who she soon married. Later, classmates called upon to make sense of the couples’ crimes would search for early signs of Homolka’s deviance, and lamely call up the fact that she owned a pair of handcuffs, or wore black nail polish, or wrote a disturbing inscription—“Remember, suicide kicks and fasting is awesome. Bones rule! Death Rules. Death Kicks. I love death. Kill the fucking world”—in a classmate’s yearbook. These could only be the words of a blossoming psychopath, unless, of course, they were simply the words of a bright, frustrated, rebellious teenage girl.

Years later—after Paul Bernardo spent months convincing Karla Homolka to “give” him her sister Tammy’s virginity, since she hadn’t saved hers for him; after Tammy, drugged by her older sister so Bernardo could rape her, aspirated her vomit and died; after Karla was complicit in Bernardo’s 1991 abduction and sexual assault of a teenage girl, and aided in the 1992 abduction and assault of another; after she stood by as Bernardo killed both girls, and helped him dispose of their bodies; after she fled Bernardo in 1993, and confessed to the police—the media would describe their crimes as a sexy, consensual folie à deux. The story went that Karla Homolka was looking for something new, something that made her feel powerful, and that something was violence. Karla Homolka would claim it was love, and that violence only crept in because of her love of Paul Bernardo, and then her mounting fear of him. Even after all the details came out, media accounts often minimized the aspects of the couple’s union that weren’t so sexy, or so suggestive of a consensual crime spree. According to Homolka, Bernardo hit her with firewood, stabbed her with a screwdriver, ripped out handfuls of her hair, slapped her, punched her, beat her with a belt, made her kneel on the floor and close her eyes as he kicked her, threw her down the stairs, defecated on her, and choked her with an electrical cord.

Karla Homolka—who went to prison in 1993 and was released, to universal public outcry, in 2005—was both guilty and innocent, and in a sense she was neither. She was guilty of allowing her moral center to erode to nothing, guilty of allowing herself to become desensitized to the cruelty that surrounded her. And she was innocent in the way that all victims of abuse are partly innocent: innocent because she was treated with a cruelty no one deserves to experience, even as she later helped her abuser inflict that cruelty on others. Love made her feel special and powerful. Then, as her life descended into nightmare, perhaps inflicting pain on other girls gave her a sense of power, too: a way of being not just another of her husband’s victims, not just another disposable girl, and not just another body in his eyes, or in society’s.

The Bernardo and Homolka case—which a Canadian friend once described to me as “Our 9/11”—has remained a national obsession because of this ineffable core. Karla Homolka did what no one could imagine doing, but was led to those actions by a series of events any young woman’s life might follow: an exciting new boyfriend, an intense infatuation, a mounting series of abuses, and then …

Somewhere, the unimaginable becomes imaginable. Somewhere, the need for love becomes a love of violence. As onlookers, we can’t separate the two any more easily than we can pull apart the motives of two perpetrators working in tandem. Compared to this ethical paradox, even the acid-trip violence of Natural Born Killers seems as innocuous as Cinderella.

This is the kind of mysterious, unsexy territory Wicked City could explore if it wants to rise above cliché and become more than an excuse for splatter montages set to a bitchin’ soundtrack. In the pilot, Ed Westwick has already delivered an impressively restrained performance, reminiscent, at its best moments, of Michael Rooker’s in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. He hints at a pathology bound up in shivering vulnerability, and one that viewers have only glimpsed in the briefest of moments. As Betty, Erika Christensen hasn’t had much time to show us her character’s depths, in part because Betty doesn’t seem to know who she really is yet. More than anything, she is lying in wait.

The pilot of Wicked City ends not with another scene of stylized gore, but with an ominous, quiet, and compelling moment of recognition between Kent and Betty. Billy Idol’s “White Wedding,” the last obligatory entry in the episode’s soundtrack, fades away (“Hey, little sister, what have you done?”), and we are left only with these two characters, and with our questions about what they might render each other capable of.